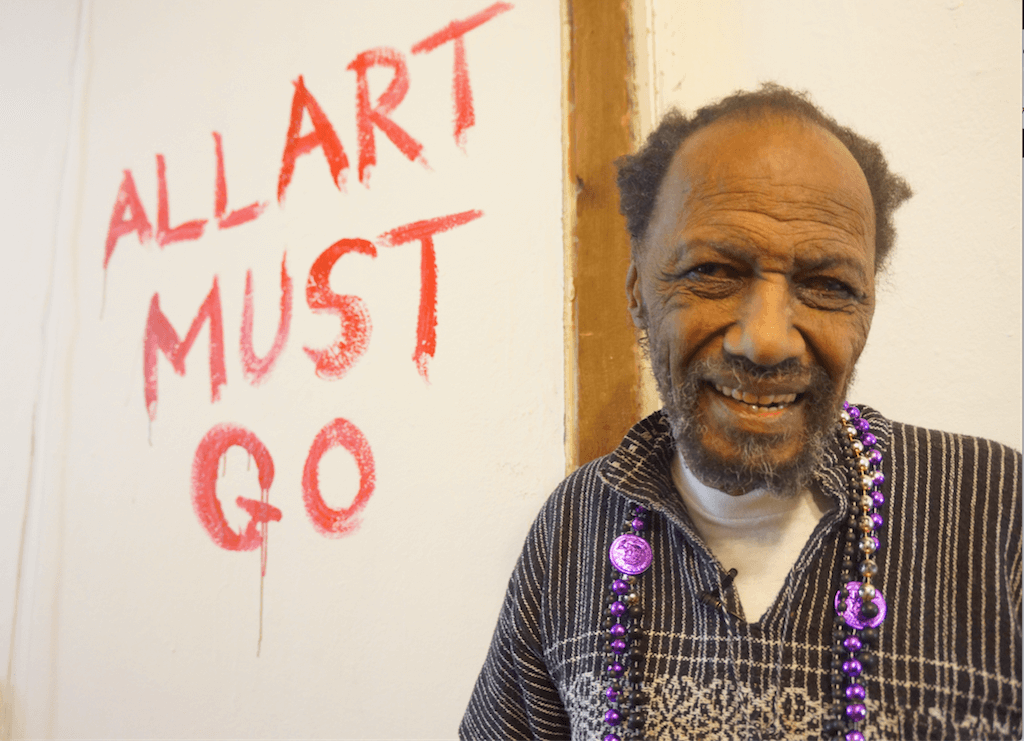

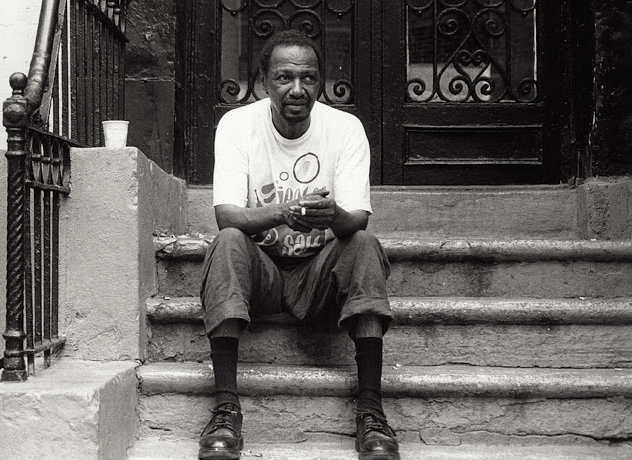

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON Updated Tues., July 9, 11 p.m. | Poet Steve Cannon, the legendary founder of the East Village’s A Gathering of the Tribes, died at 2 a.m. on Sun., July 7. He was 84.

Cannon was rehabbing from a broken hip at the VillageCare Rehabilitation and Nursing Center, at 214 W. Houston St., across from the Film Forum. He had fallen and broken his hip in his East Village home on June 12, after which he had surgery at the Veterans Affairs Hospital on E. 23rd St. and First Ave. He transferred to VillageCare on Sat., June 29, according to poet and friend Melanie Maria Goodreaux.

Goodreaux said Cannon went to the V.A. for surgery because he was a former paratrooper. She had seen him the Tuesday before he died.

“He said he was bored in the hospital and he was really looking forward to going home,” she said. “He was still talking, still laughing, and we were still talking about art.

“He was there to rehab his hip,” she said. “He had to learn to stand and walk around. He was going to be in rehab about a month.”

But three days before he died, his condition took a turn for the worse. Cannon was sent to the intensive care unit at the V.A. Hospital Saturday night. Among those at his bedside in his last hours were his daughter Melanie Best and poets Bob Holman and Chavisa Woods. Also there during the final week were poet Steve Dalachinsky and artist/writer Yuko Otomo.

According to those with him in his final days, Cannon apparently had an abscess that burst. Indeed, Woods, who was with Cannon in the ambulance to the I.C.U., said she believes the cause of death was septic shock. Holman said he doesn’t want to discuss it publicly yet.

East Village performance artist David Leslie said Cannon had been suffering from a bed sore when he recently visited.

“He had a cyst or some sort of abscess,” he said. “He said he had gotten like a bed sore on his ass, which needed to be cleaned up.”

Leslie said that he had, by coincidence, been visiting Cannon with some friends just about 40 hours before his death. Cannon had been sleeping, and so he woke him up.

“Steve seemed perfectly fine. He was joking and in good spirits,” he said, “and the next thing I heard, he had died.”

But Goodreaux said, although people are saying sepsis, she thinks it was simply Cannon’s age combined with the serious hip injury.

“If he wasn’t blind, they probably would have let him out by now,” Leslie added. “People get out with a broken hip. But you wouldn’t want a blind person stumbling around with a broken hip.”

Cannon went blind from glaucoma in the late 1980s.

He was born in New Orleans, the youngest of 12 or 13 children, and raised by his grandparents. He moved to New York City in the early 1960s. Early on, he collaborated with black artistic luminaries novelist Ishmael Reed and artist David Hammons.

In 1990, Cannon created the East Village/Lower East Side literary magazine A Gathering of the Tribes, and soon afterward turned his East Village home into the Tribes literary salon and art gallery. In 2014, Cannon was forced to vacate the space, though he had thought he had an agreement to live there till he died.

“It’s the end of an era,” said Holman, the founder of Bowery Poetry Club. “The Gathering of the Tribes was just that, where all artists were welcomed under one roof. He embodied the generosity of art. Artists who were doing it, or artists who didn’t know they were artists. There was an ever-welcome mat at Steve’s doorstep. His was the ‘In’ that always had room. The loss is incalculable.

“And now we’re in the new New York, which seems to be looking everywhere — technology, globally — but is missing the human contact, which is what Steve saw everywhere. He was the ‘Great Connector’ — the person at the center of the tribes.”

Holman said that even in his final years, in his Habitat for Humanity apartment on Avenue D, Cannon’s place remained a gathering spot.

“There was a constant stream of visitors,” he said. “The door was unlocked, as it had been on Third St. There was always someone there.”

It was East Village journalist Sarah Ferguson who found Cannon that apartment after he lost the E. Third St. space, Holman noted.

Similarly, Woods said, “He was magnetic, magnanimous. He created the most open space I’ve ever participated in — for better and for worse. He was expansive, warm, explosive, energetic, eccentric and strange. He really believed in the mission of bringing people of diverse backgrounds and perspectives together for the purpose of creating art and community. And sometimes it was really messy and sometimes it was spectacular.”

Cannon was known for his tough love toward young poets.

Poet/playwright Liza Jessie Peterson posted a fond recollection on Facebook of Cannon at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe shouting at young poets to dispense with the introductions and explanations of their work and “Just read the damn poem!”

“He was definitely a guide. He gave counsel,” Peterson said. “He was just on the surface like that — really mean, a strict teacher. But he brought out the best in you. He was tough, he wasn’t mean. He just raised the standard. He gave us, like backbone, courage, to get up there and just, ‘Read the goddamn poem!’ … He would just scream it.”

Sitting at the corner of the bar, Cannon was the toughest critic in the place.

“It was like Steve’s sacred spot at the bar,” she recalled. “This was in the ’90s, you could still smoke inside. He was just this Lower East Side cat. He just had a keen ear. When you’re blind, it heightens the other senses. He didn’t want no bull crap: Just get up on that microphone.”

Today a playwright and actress, Peterson has been nominated for a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Solo Performance for her acting in her play “The Peculiar Patriot.”

Goodreaux noted she knew Cannon for 27 years, ever since arriving in the city.

“When I moved to New York in the late ’90s, I would read the newspaper to him in the morning, and his e-mails and books,” she recalled. “Not just me — many, many people read to him.”

This January, Cannon published a book of Goodreaux’s poems, “Black Jelly,” and Goodreaux said his impact as an independent publisher must be acknowledged.

“I think he’s one of the most important publishers in the history of the city,” she stated.

On top of that, Cannon was always simply encouraging people to write and hone their chops.

“If we went to a movie, he’d say, ‘Write a review of it, put it up on a Web site,’” she said. “He was constantly pushing people to write. He wanted to educate people and he wanted them to understand the importance of being an artist. But he was also down to earth.

“He went to every play I ever had,” she recalled. “He was constantly hungry for art.”

Woods, who worked for Cannon for seven years and said he was her longtime mentor, is the author of four books, including “Things To Do When You’re a Goth in the Country.” She said she would often read entire books for him in one sitting, sometimes lasting up to eight hours. Afterward, they would discuss each book. If Cannon knew the authors, he’d talk about their writing and share anecdotes of his encounters with them.

Holman noted that one thing Cannon regularly had read to him was The Villager newspaper, of which he was a fan.

“It was his newspaper,” he said. “The Villager was a regular part of his literary diet, for sure. That and The New York Times, the London Review of Books. He was a true intellectual, an intellectual of the people.”

Cannon was married twice. His son from his first marriage died in his teens from hemophilia. Cannon was the adoptive father of five daughters from his second marriage to the late poet Zoe Angelsey. He has at least two sisters living in New Orleans.

Details were not immediately available about a memorial, but friends said there might be something this week, and that they are working with the family to plan a memorial later, possibly in the fall.