BY DAVID NOH | nce upon a time, on the magical island of Manhattan, there lived three princesses named Stettheimer. Born to a wealthy, elite German Jewish family, their father, a banker, deserted them in childhood, but their mother, Rosetta, had enough money of her own to enable her daughters to create their own special kingdom, devoted to art and beauty in all forms.

Call them what you will, dilettantes, whatever, but, with their originality, wit, divine taste, and incessant pursuit of aesthetic excellence, these girls were anything but Kardashians. Though they personified the “new woman” of the 20th century, smoking, wearing pants, avoiding romance, marriage, and children, and embracing artistic friendship above all else, they forever retained that now nearly forgotten attribute –– being lady-like.

In their exclusive salon in the French Renaissance Alwyn Court on West 58th Street, Ettie had a philosophy Ph.D. and was the writer and conversationalist of the family, richly caparisoned in her red wig, diamonds, and brocade draperies, Carrie favored fashions of the past over modern wear and played hostess, planning menus and overseeing the hectically bohemian household, while Florine (1871-1944), in her ubiquitous white satin pants, painted.

The interchangeable art and life of Florine Stettheimer

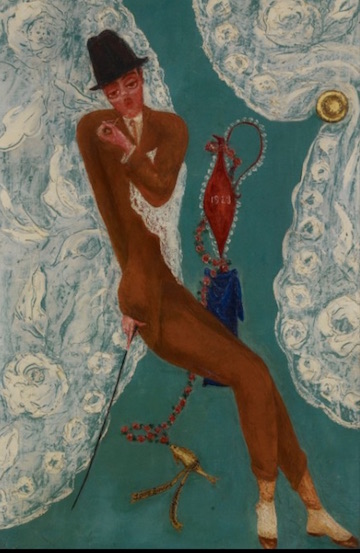

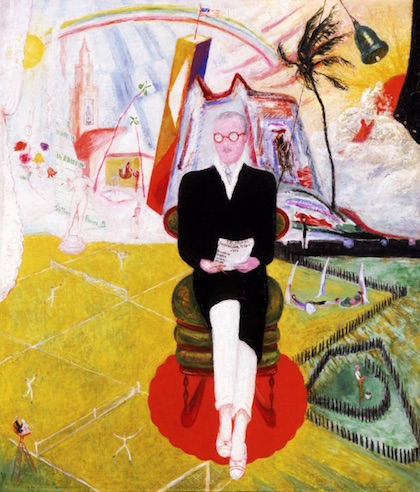

Oh, boy, did she paint! Great, brilliantly hued, highly fanciful and stylized portraits of her family and famous contemporaries, and tableaux — “Asbury Park South,” the hilarious “Spring Sale at Bendel’s,” “Heat,” a view of her clan, expiring from a Manhattan summer — which captured the heady, rarefied world in which she and her sisters, forever single, moved. Florine, who rarely exhibited her work publicly, especially after an unsuccessful Knoedler Gallery show in 1916, when she was in her 40s, decided to unveil her paintings at their parties, which were attended by the likes of Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Stieglitz, Carl Van Vechten, Georgia O’Keefe, Elie Nadelman, and Gaston Lachaise. She continued to refuse solo show offers from dealers like Stieglitz, causing O’Keefe to sigh, “I wish you would become ordinary like the rest of us and show your paintings this year!” Florine once remarked, “Having other people owning your paintings is like letting them wear your clothes!”

She remains today the best-known of the sisters, and the Jewish Museum has mounted a bewitching, deeply charming show devoted to her, entitled “Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry.” It’s a strong rebuke to critics who, in the words of curator Stephen Brown, have long typecast her “as a lightweight feminine artist with a whimsical bent… a view belied by her powerful thinking of portraiture and her astute adaptation of European vanguard ideas, most notably Symbolism, to uniquely American imagery.”

The show is the perfect summery delight: intensely feminine and with an airy, breezy layout that shows off Stettheimer’s exquisite work in a completely appropriate and very lovely light. I had always wrongly assumed from her boldly naïf style that Florine was self-taught, so therefore was struck by the impressively confident technique she displayed at age 14 with a hand-painted set of Tarot cards, also a nude study and finely wrought head of a girl, the result of art studies in Germany, Paris, and Spain, and happy immersion in Titian, Diego Velázquez, Viennese Art Nouveau, and the contemporary craze for Orientalism, triggered by the Ballet Russe, whose “Afternoon of a Faun” she had caught in Paris in 1912.

Duchamp, with whom she was quite close, was a champion of her. A fetching portrait of Stettheimer by him is included here, and there are a couple of charming portraits of Duchamp, by her, one of which has a fiendishly clever frame she created, as well, using his initials as its chief decoration. Duchamp also contributed a miniature of his groundbreaking “Nude Descending a Staircase” to hang on a wall of the Stettheimer Doll House, which, on permanent display at the Museum of the City of New York, was, for years, most people’s main perception of the Stettheimers. The 1947 book about this treasure — a veritable time capsule, overseen by Carrie, of their home and lives, with other stamp-sized original artworks by Lachaise, Alexander Archipenko, George Bellows, and Marguerite Zorach — with a foreword by Ettie, has been reprinted and is on sale at the Jewish Museum, along with a rare book of Florine’s Dada-esque poetry, “The Crystal Flowers of Florine Stettheimer” (1949), edited by Ettie.

Florine’s most public achievement was her costume and set design for the Virgil Thomson-Gertrude Stein operatic collaboration “Four Saints in Three Acts.” Eschewing traditional sketches, she instead executed her ideas in miniature models and figurines, tricked up with paper, feathers, fabric, and beads. The complete set of them is on loan from her collection of papers at Columbia University, and, panoramically displayed, they have the effervescent, instantly smile-inducing charm of any conceit of Calder’s. Actual though silent footage from the 1934 production is screened on an adjacent wall, where one can appreciate the dazzling novelty of Stettheimer’s cellophane-trimmed vision — which certainly must have helped to put this precious divertissement over — as well as its all-black cast, surprisingly playing saints like Teresa of Avila and Ignatius of Loyola, long before the color-blind casting of “Hamilton.”

Florine lived with her mother until she was in her 60s, and became reclusive, dying at 72. She had requested that the art in her studio be destroyed, which, thankfully, was ignored by her family, although Ettie edited out all personal matters from her journals and papers before donating them to Columbia and Yale. The question about her exact sexuality remains unanswered, although she certainly welcomed gay men in her life, as attested to by the numerous sylph-like fops, famous and near-famous, in her canvases, nearly as ubiquitous as Al Hirschfeld’s “Ninas.” Queer scholars have long embraced her as one of “the family,” but perhaps the clearest explanation of her true nature was expressed in a poem of hers:

| HECKSCHER MUSEUM OF ART, HUNTINGTON, NEW YORK. GIFT OF THE BAKER / PISANO COLLECTION

Occasionally

A human being

Saw my light

Rushed in

Got singed

Got scared

Rushed out

Called fire

Or it happened

That he tried

To subdue it

Or it happened

He tried to extinguish it

Never did a friend

Enjoy it

The way it was

So I learned to

Turn it low

Turn it out

When I meet a stranger –

Out of courtesy

I turn on a soft

Pink light

Which is found modest

Even charming

It is a protection

Against wear

And tears

And when

I am rid of

The Always-to-be-Stranger

I turn on my light

And become myself

FLORINE STETTHEIMER: PAINTING POETRY | The Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Ave. at 92nd St. | Through Sep.24: Fri.-Tue., 11 a.m.-5:45 p.m.; Thu., 11 a.m.-8 p.m. | $15; $12 for seniors; $7.50 for students | thejewishmuseum.org