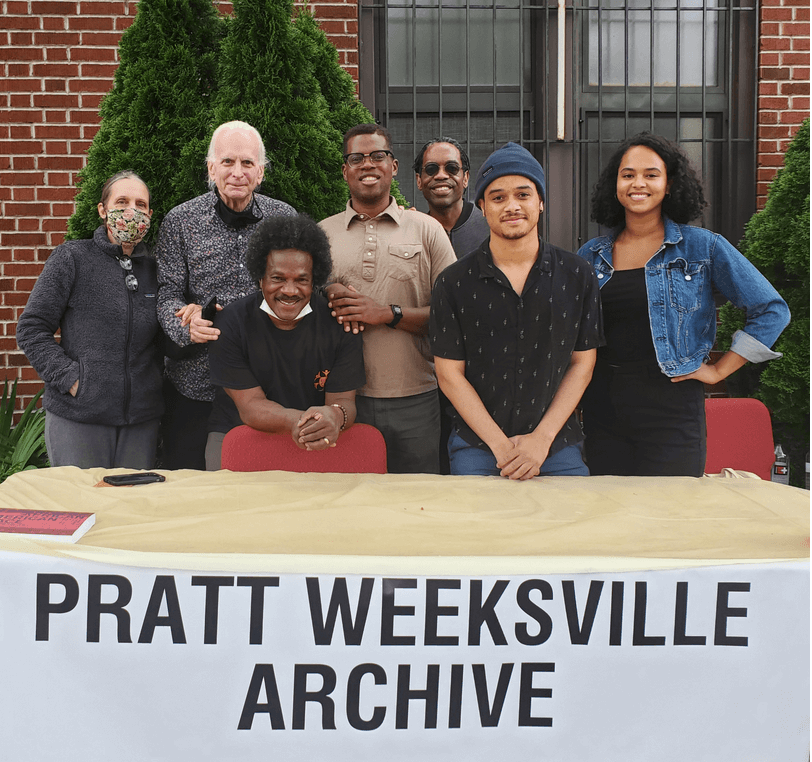

Architecture students from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn have been collaborating with the Weeksville Heritage Center to create a publicly-accessible oral history project on the history of the Weeksville community, one of the first Black settlements in the country.

Weeksville, located in Central Brooklyn, regained cultural and historical significance in 1968 when Pratt Institute professor and local historian James Hurley organized a workshop exploring the neighborhood. After combing through archives and surveying the current streets and architecture, Hurley and his students discovered the last remnants of one of the first free Black communities.

Launched in the fall of 2020 and supported by a Taconic Fellowship from the Pratt Center for Community Development, continuing to document the Weeksville community’s history remains a great priority for Jeffrey Hogrefe – professor of humanities and media studies and cofounder of the Architecture Writing Program, as well as Scott Ruff – professors of architecture and co-creators of the Pratt Weeksville Archive, in addition to student collaborators Cierra Francillon and Caleb-Joshua Spring.

The team has so far produced six oral histories, with more planned with the assistance of the participation of the Bethel Tabernacle and other Pratt team members.

“We are really just in our infancy here,” said Hogrefe to amNew York on March 16. “Our interest arose in the archive itself. It arose out of our ongoing interest in African American space and looking for ways in which we can encourage social justice through this.”

One of the biggest takeaways the team has learned from conducting the oral history project is Weeksville’s historical position as a free Black community – a rarity at the time – and looking at the level of homemaking and lifestyles these individuals lead after escaping enslavement and looking for opportunities for their own.

“[Black individuals] had to flee New York City because of all the racism that was going on there, [and we are] kind of looking at the complexities of life there,” said Spring in an interview with amNew York. “Everyone [had] exactly what they needed and they were very close-knit, however because of things like developers and gentrification, this homemaking was kind of splintered and broken. Things that were really important to the community were lost, and because of that a lot of the history has been splintered and we’ve lost a lot of the recordings of what life was there in Weeksville.”

The archive is intended to get in touch with community members still residing in Weeksville and have them recount their lives and experiences to get a complete story of how it was, so the community can piece back together and become connected to some of the history that was lost – while ultimately creating more history as the project continues.

The students go about interviewing Weeksville residents that they have identified as potentially good sources of information to add to their oral archive, which they and the Pratt Weeksville Archive hope will become an open and accessible project for all residents interested in learning more about the settlement. To add further longevity to the work, the Pratt team has created a framework for using cell phones to engage and empower community members to interview one another, which is also a means of ensuring that authorship of the narrative of this space is in the hands of its residents.

“By having these archives, it is acknowledging a continuing memory of these spaces that held a self-sustaining Black community,” said Francillon. “By continuing all of these archives we can continue its memory, but also by bolstering the historical presence of something that was previously erased, we are bringing it back.”

You can read more about the initiative here.

Last updated 3/21/2022 9:06 am