By JERRY TALLMER

If there’s anyone more American than Red Grooms, you’ll have to show me. Mark Twain, maybe. Steve McQueen, maybe. Gil Hodges, holding the ball out for the ump to see that shoe polish. Red is also a Downtown New York American ne plus ultra, by way of Nashville, Tennessee, where Charles Rogers Grooms was born June 7, 1937, at the height of the Depression.

Every so often he ventures Uptown, either to sketch a locale, or to take in a movie or an exhibit, or to drop in on an exhibition of his own stuff — like the one at which we find him at this very moment, “Red Grooms: New Works in Wood,” at the Marlborough Gallery on 57th Street.

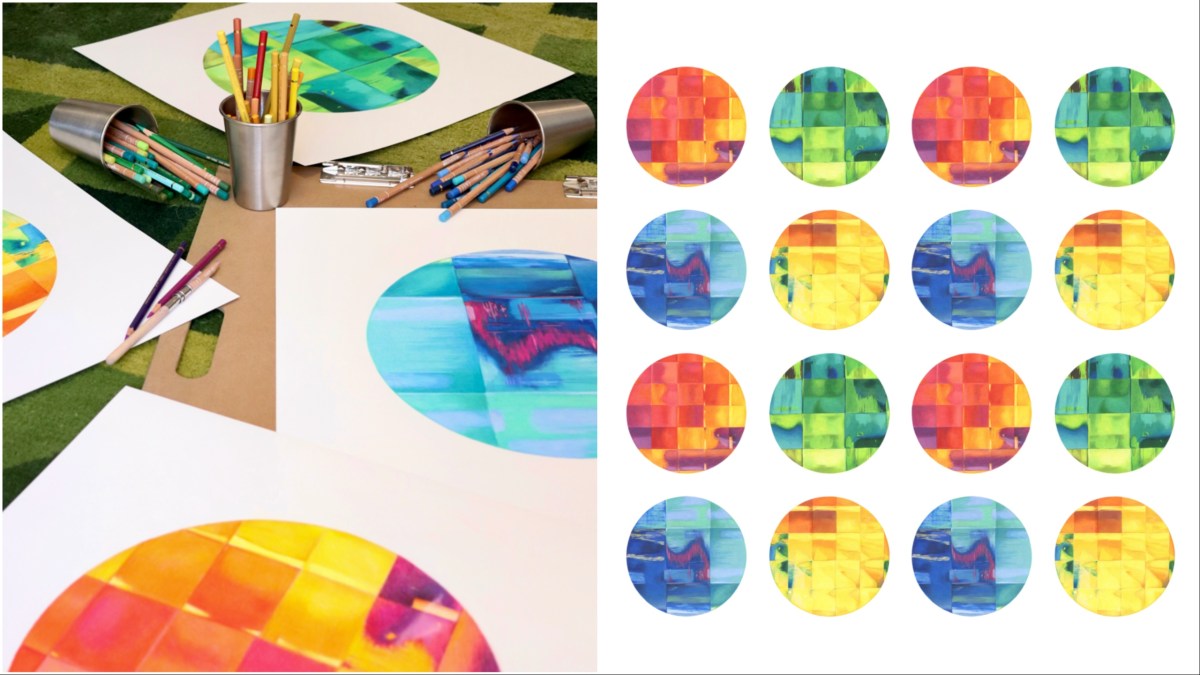

The centerpiece of the show, a little more than 10 feet wide (by 71 inches high, 17 5/8 inches deep) is the depiction of a gangster’s funeral in typical Red Grooms materials: “Acrylics on wood, with wallpaper, Venetian blinds and light bulb,” as Red explains.

We view that funeral through those Venetian blinds from a window across the street — the vantage point of a handful of FBI agents equipped with field glasses and listening equipment.

The construction is titled “A Death in the Family.” Red turns to this reporter and asks: “Who wrote that book?” James Agee, he’s told — the Agee who, around the time Red was born, was with photographer Walker Evans sharing the lives of Alabama sharecroppers for what would turn out to be “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

“Oh yeah, he’s great,” says Red Grooms. “He’s from Knoxville, you know.”

He nudges the reporter closer to the 10-foot gangster funeral. “See?” Red says. “The limousines. The casket. The mourners. Then I thought I could frame it — with the surveillance thing, the FBI. I always liked Jack Levine’s gangster paintings.”

Grooms is a large man, always was, and his now white hair is in a brush cut that accentuates the solid rectangularity of his head and face — rather as if he’d carved it himself for an oversized toy soldier out of “The Nutcracker Suite.”

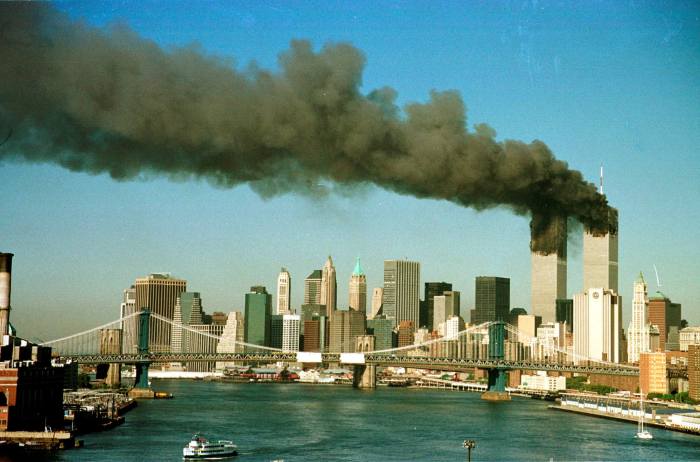

With a slow smile he says: “I lived for 10 years, from 1965 to 1975, at the corner of Grand and Mulberry. The northwest corner, where there’s an Italian deli. Saw a lot of action there. Once some mobster got shot right in front of our door. The police outlined the body in chalk. My daughter was 5. She never forgot it.”

The daughter is Saskia, who now lives in Amherst, Mass., and has two daughters of her own. Saskia’s mother is Mimi Gross Grooms, the artist who — herself the daughter of sculptor Chaim Gross — was Red’s first wife and worked with him on a host of things including the extraordinary breakthrough “Ruckus Manhattan” of 1976.

“Mimi was primary partner in ‘Ruckus,’” he says. “She’s still right there Downtown, on White Street. She’s doing great.”

There are some 30 pieces altogether in the Marlborough show. Another impressive one is “Joseph’s Bridge,” looked at from the Brooklyn end of the Brooklyn Bridge, complete with cars, taxis, hikers, joggers and a big-butted bicyclist, all this in bright reds, browns, blues, yellows.

The title is a tribute to Joseph Stella. “Quite a great artist,” says artist Grooms. “Nobody’s ever going to beat his paintings of that bridge. I was thinking of doing this piece in the colors he used, but they’re peculiar — dark, actually — so I abandoned that idea.”

Another big, buzzing, blooming piece is “Canal-Walker Split,” looking west on a Canal Street full of cars, trucks, taxis, past a billboard that blares “TAKE A BUD BREAK.”

Grooms links his fingers atop his brush cut and says: “I have an 1840 print of the same scene. The exact same configuration, the exact same split [of Walker and Canal Streets] — amazing.”

But not the Bud sign . . .

“No. I made that up.”

D’you drink beer, Red?

“Yeah, I do. Especially draft. What I do like is a simple Bud in a cup at the Knicks games. Yeah, I’m a fan. They pooped out this year so badly. A disaster. So right now I’m in sports limbo. What to do on weekends? I wish I liked baseball more.”

He thinks of something applicable:

“I was actually commissioned by Charles Bronfman to do a portrait of the Montreal Expos when he owned the team, somewhere in the 1980s. Gary Carter was still their catcher. I’ve done the Knicks several times. Almost did the Knicks for a New Yorker [magazine] cover. That was when Lee Lorenz, a great friend, became the New Yorker’s art editor, and brought me in. I did three covers for them in all.

“Right now I have a commission from Jeff Lauria [post-Bronfman Expos owner, current Florida Marlins owner] to do a sports piece for him, but not about the Marlins. I did Mike Tyson once. Went to Atlantic City to see him fight Truth Williams. Knocked Williams out in 45 seconds. I went with my sister-in-law because my wife doesn’t like sports.”

Red’s wife — “and chief advisor” — is Lysiane Luong, a painter and sculptor in her own right. They met one summer in the South of France, have been married since 1987. “She doesn’t spare me [in applying an outside eye to the work]. That’s good, you know.” Pause. “But you really have to do what you think you have to do.” Pause. “Sometimes they’re wrong, you know, and sometimes they’re not.”

He really does walk around town with a sketchbook.

“I never was into photography, but with these new quick-snap cameras, it can be helpful. Still, the drawings are more like the language the thing is going to be in.”

By “language,” he means the Groomsian essence — the “contrariness” and “impertinen[ce]” Marco Livingstone talks about in an essay in a new “Red Grooms” book coming from Rizzoli in June.

“It’s pretty much the city makes the language,” Red tells interviewer Timothy Hyman in that same book. He also tells Hyman: “That’s what I deal with: the cliches. That’s why I could work with a lot of other artists as associates. Everyone knew the references.”

Here in the Marlborough he says: “I’ve worked with a lot of people over the years — a lot. Now there’s only one: Tom Burckhardt. He’s wonderful. It’s kind of just boiled down to him. He’s a painter himself, with the Tibor de Nagy Gallery” — where Grooms has a show of prints and watercolors concurrent with the Marlborough exhibit.

“About seven years ago, Tom and I made a 42-foot-diameter working carousel — the ‘Tennessee Foxtrot Carousel,’ in Nashville — with 36 characters. Tom carved them and I painted them. I’d be impatient with anybody not so skilled.

“That whole thing about collaboration is difficult. In a way, it’s easy to be watered down [through collaboration]. We humans actually enjoy working together, and following somebody’s leadership.

“I am really not good at mechanics,” says Red Grooms. “I can think: ‘If this moved, it would be fun’ — but I don’t know how to do it.” He laughs out loud as he remembers Jean Tinguely, the Swiss artist-sculptor-inventor whose triumphs were avant-garde Rube Goldberg machines that destroyed themselves.

Tom Burckhardt has his own share of Swiss blood. Now going on 40, he’s the son of artists Rudy Burckhardt and Yvonne Jacquette, and thereby a descendant of the eminent art historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897).

Virtually the first person Red Grooms met when he got to New York circa 1958 was the artist Alex Katz (whose “cardboard cutouts” are reflected even to this day in Grooms pieces like “A Death in the Family”). “I was lucky to meet Alex, and he became the catalyst,” Grooms says. He thinks it was through Katz that he met Rudy Burckhardt, the self-effacing, spirited, sweet-souled artist, photographer, filmmaker, poet, everything else who affected many people, many lives, Red’s among them.

Grooms is of that generation that exploded in New York in the late 1950s: Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Dine, Kaprow. With Alan Kaprow he made early Happenings, and with Rudy Burckhardt — after a wonderful year in Italy with Mimi — Red made a film called “Shoot the Moon,” a takeoff on the epic Georges Melies 1902 “Le Voyage dans la Lune.”

He’d started as a watercolorist and collagist out of the Chicago Art Institute, and studied at the New School, here on 12th Street, and with Hans Hoffman in Provincetown, but, he says, “I couldn’t maintain the abstract. It was just a moment that kind of opened up. I was young, hadn’t settled in, was a big lover of movies. Even in Italy I made a small eight-minute film, ‘The Unwelcome Guest,’ and Mimi made an amazing thing, a shadow puppet theater. A friend got us a horse, and with that horse we took that little theater and gave puppet shows at every stop all over Italy, Venice, Florence, everywhere.”

His first three months in New York, Red lived at the McBurney YMCA on 23rd Street. “Then I moved to 24th Street, just off Sixth Avenue, and then to two other lofts at 24th and Sixth, and then in 1959 I took a place at Delancey and Norfolk, a little building that’s still there actually.”

But for years now his home has been in the American Thread Building on West Broadway, while for 35 years he’s had a spacious studio on Walker Street. “I used to say ‘for 30 years.’ The last five years kind of snuck up quickly.”

Red’s mother, Wilhelmina Rogers Grooms, is 96. His father, the late Gerald Grooms, was an equipment engineer with the Tennessee Highway Department. “I went with him, taking inventory at every little town in Tennessee.”

Nowadays, as ever, some of Red’s pieces take as long as six months to make.

“Sometimes they stay around quite a while. I often work on two or three at once. The gangster’s funeral and the bridge were going on at the same time.”

Like so many other people, he had come through the “junk art” period, when you went around collecting odds and ends off the street — the Louise Nevelson method. “She was the great master of it; they don’t make them like that any more. You know,” says Red, “for a long time, it’s just a hunk of wood. It doesn’t look much like anything.

“I swear, I’ve been doing this for 50 years, and I never spent one day when it looked like I was getting anywhere.”

Look again, Red. Just look all around you.

RED GROOMS: New Works in Wood. Marlborough Gallery, 40 West 57th Street, 212-541-4900, through June 5.