The MTA needs revenues from congestion pricing yesterday, according to a new report by a government watchdog group.

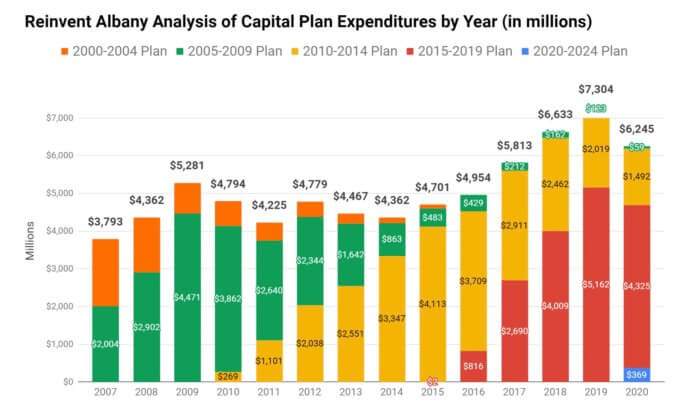

Reinvent Albany reported that the mass transit agency has secured less than 4% of the cash needed for its ambitious, nearly $55 billion five-year capital plan to modernize the ailing subway and bus systems.

“The MTA literally cannot afford to lose congestion pricing revenues,” said Rachael Fauss, a senior researcher with Reinvent Albany, who co-wrote the report.

MTA officials have only $2 billion on hand out of $54.8 billion budgeted for the 2020-2024 capital plan 18 months into its schedule, according to the analysis released Thursday, Aug. 19.

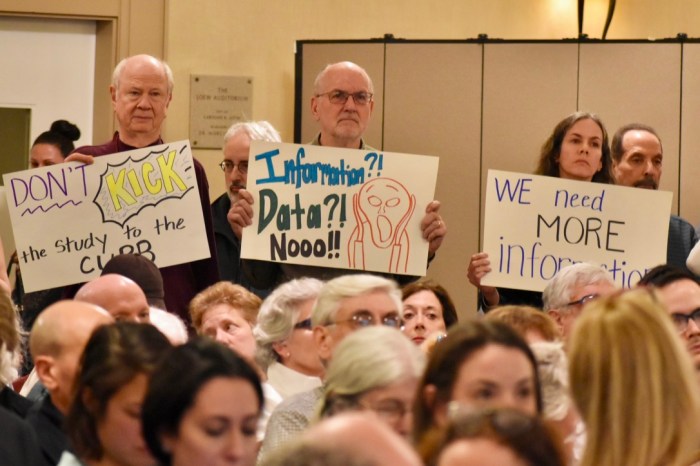

The agency claimed in July that half of funding is “secure,” but only 3.7% of funds have arrived so far as almost a third of the capital program’s timeline has passed. That’s slower than previous capital plans 18 months in, when 7.3% was funded for the 2015-2019 plan and 11% for the 2010-2014 plan.

The first-in-the-nation proposal to charge drivers entering Manhattan’s “Central Business District” at or below 60th Street is crucial for funding the current capital plan by unlocking $15 billion in bonds for MTA projects, the single largest money source, in addition to providing $1 billion in annual tolling revenues.

Advocates also hail the tolling proposal for reducing congestion and pollution, supporting a move away from car-dependent commutes to public transit.

The money is needed to pay for the capital plan’s projects to modernizing the subway’s Depression-era signals, buying new train cars and buses, adding accessibility upgrades, and for big ticket items like the Second Avenue Subway and Penn Station Access.

Congestion pricing was first approved in the state legislature in 2019 and was originally slated to go into effect in January 2021, but was stalled for two years under the President Trump administration.

But transit bigwigs and state politicos have shown little progress on congestion pricing since the federal government allowed MTA to move forward with a so-called environmental assessment in March, investigating the impacts of congestion pricing on the five boroughs and commuters from the tri-state area.

The MTA told The New York Times this week that the assessment would take 16 months, delaying implementation of the charge until after incoming Governor Kathy Hochul faces voters in the November 2022 general election.

Hochul, who will control the MTA once outgoing Governor Andrew Cuomo resigns next week, sounded lukewarm when a spokeswoman told the Gray Lady that the soon-to-be governor “will need to evaluate [congestion pricing] further given the constantly changing impact of COVID-19 on commuters.”

The agency doesn’t expect the $1 billion in annual revenues to kick in until 2023, but Mayor Bill de Blasio — who has been beating the drum on congestion pricing in his final months in office after initial skepticism — lambasted the 16-month timeline as “ridiculous” Tuesday, saying MTA needs to get going faster.

In 2019, the MTA told the US Department of Transportation assessment would only take three months, reported Streetsblog, but transit officials have since forecast a longer timeline due to public outreach they plan to do across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, along with a handful of Native American tribes.

Meanwhile, MTA Chief Financial Officer Robert Foran told the authority’s board in June that they were fine without the congestion pricing funds right away thanks to other income from state internet sales and mansion taxes.

“Right now, we’re fronting the capital program with the sales tax moneys that we have and the mansion tax moneys that we have, so we’re not in a position now to really be needing, absolutely at this time, point in time, the congestion pricing proceeds for the capital program,” said Foran at the June 23 meeting.

The new report argues that MTA won’t be fine and will need all the money it can get to dig its way out the disastrous COVID-19 budget impacts.

The pandemic left a $2.9 billion hole in the capital program, due to the MTA borrowing money from the federal government to stay afloat as ridership plummeted, according to a previous report by State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli.

The agency also diverted nearly $500 million in funds from the capital program to support its operating budget to keep its transit system going during the viral outbreak.

MTA and outgoing Governor Andrew Cuomo have touted that lower ridership during the pandemic has allowed them to accelerate capital projects, but actual spending on the program slowed in 2020, Reinvent Albany’s report shows.

An additional $10.7 billion in federal funds for the capital plan have already been accounted for, and some of that money from Washington might have to go toward projects MTA would had paid for itself before COVID-19 devastated its finances, according to the report.

Delaying the much-needed revenue from congestion pricing could destabilize the MTA’s finances and put pressure on the agency to do deep service cuts, just when it wants to rebuild its ridership, which is still less than half on the subways compared to pre-pandemic.

“The MTA, led by Governor Hochul, needs to quickly secure its crucial capital funding sources, including congestion pricing, as the agency recovers financially from the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Fauss.

MTA’s senior advisor on congestion pricing Ken Lovett responded in a statement saying the agency won’t need the tolling revenues for “several years,” thanks to other funding sources.

“We wish Reinvent Albany had at least contacted us for this report. If they had, they would have known that after a year where the capital program was mostly put on hold because of the COVID-19 crisis, we are now going full tilt and do not require congestion pricing revenues for several years,” Lovett said.

“The state Legislature has previously authorized the use of additional state and city sales taxes and the mansion tax for the 2020-24 capital program and we are using such funds, which we anticipate comes to about $10 billion, including proceeds of city sales tax bonds, other bonds supported by State sales taxes and pay-as-you-go capital funds,” the rep added. “Not only are these sources of funding available, but — as publicly stated time and again — we always planned to use them before relying on revenues from congestion pricing.”

Hochul’s office did not respond by press time.