BY ROBERT HEIDE | The evening of June 28, 1969, is the starting point of the gay revolution at what was once seen as a notorious mafia-run gay hustler bar by some uptight Villagers — and in particular by the New York Police Department — the Stonewall Inn, at 51 Christopher St.

The place was originally a horse stable, almost 200 years old in 1930 when it was converted into a rental hall for business banquets, birthday and wedding parties. In the ’60s it opened as a gay bar and attracted a mix of wild drag queens and young gay men.

Drags and transvestites were often excluded from the more exclusive gay men’s Village spots, like Julius’ and Lenny’s Hideaway, both on W. 10th St., and the Old Colony and Mary’s, on Eighth St. The cellar dive that was known as Lenny’s is now Smalls Jazz Club.

I myself hit the Stonewall a few times back in the early days with a brownette, pointy-toothed Candy Darling. This was before he/she was given a makeover by the flamboyant Off Off Broadway theater director Ron Link, who taught Candy how to do her makeup in 1930s movie-star style.

The newly glamorized Candy was presented in a show written by Jackie Curtis at Bastiano’s Cellar Studio Theater in the Village called “Glamour, Glory and Gold,” which featured in his first stage role a young actor named Robert De Niro. For the Candy transformation, Link got out a white henna powder concoction that, when mixed with peroxide and pure ammonia and applied to dark hair, turned it platinum-white blonde, thus changing a drab Candy into a Kim Novak/Jean Harlow blonde bombshell.

Eventually, Candy went on to become a Warhol Superstar: for the final makeover touch Warhol paid to have Candy’s teeth capped pearly white. At about the same time, drag performers Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn also jumped into the Warhol superstar film scene at the Factory.

There are many stories and myths about the rebellion at the Stonewall and the riots that followed and one of them has a Stonewall regular, a black drag named Marsha, hitting a cop over the head with a high-heeled shoe on the first night of the famous police raid. Some of the Black Marsha myth may have been concocted or exaggerated by the three-day protest crowd. It is known that at one point the police were actually locked (along with Howard Smith, the Village Voice “Scenes” columnist) inside the place by the angry drags and queens and their sympathizers fed up with the constant raids and continuous harassment.

My partner, John Gilman, and I watched some of the big happenings from Christopher Park, not realizing at that time the full importance these events would ultimately have on gay history, gay identity, the gay revolution and the gay liberation that followed. Now, same-sex marriage is O.K. and, in the summer of 2015 with Olympian Bruce Jenner becoming Caitlyn Jenner, sex change has become the new “normal” in America, leading us to a completely different way of looking at the world of transgenders, transsexuals and transvestites.

Another important gay scene that was taking place in the Village, even before the Stonewall opened its doors as a gay hotspot, was the Caffe Cino storefront coffeehouse theater, now known as the first Off Off Broadway theater, which had a 10-year span from 1958 to 1968.

The Cino, at 31 Cornelia St., run by Joe Cino, has become legendary for the plays that first presented “out” gay relationships. It was at the Cino that Joe, sometimes wearing an American flag cape, ordered the gay male writers on the premises to write plays for men that expressed their own gay lifestyle, suggesting to them, “It’s magic time — do your own thing, and do what you have to do.”

These commandments from Joe, a motivational leader and mentor who inspired writers and actors alike to do whatever they so wanted in the place, became iconic Sixties jargon. Cino himself and his lover, Jon Torrey, the lighting designer who wired the Caffe’s electricity to a Cornelia St. lamppost and later accidentally electrocuted himself (no, they never paid a bill to Con Edison), along with resident artist Kenny Burgess, resident lighting designer Johnny Dodd and his companion Michael Smith, an influential Village Voice critic and playwright, and others attracted not just gay writers and actors, but “straight” writers and actors, and gay and straight audiences, as well. Also not to be forgotten would be the provolone and pimento sandwiches and the best cup of cappuccino and Italian puff pastries in the Village.

(Dodd and Smith lived down the block at 5 Cornelia St. where the legendary Judson Church dancer and Warhol film star Fredie Herko did a ballet leap out the window of the fifth-floor apartment window high on LSD, landing on the pavement below.)

Some of the characters and talented personalities frequently on the scene at the Caffe Cino included Angelo Lovullo, Joe’s childhood friend from Buffalo; the brilliant actor Charles Stanley; director Robert Dahdah, who produced and directed “Dames at Sea,” as well as dozens of other plays at the tiny theater; actor and director Magie Dominic; set designer and director Donald L. Brooks; the Hedy Lamar lookalike Lady Hope Stansbury; the mercurial Eddie Barton; the notorious Cornelia Street Art Gallery owner Frank Thompson; famous drop-ins, like the existential writer and author of “The Outsider,” Colin Wilson; Broadway theatrical producer Richard Barr, playwright exemplar Edward Albee; director Tom O’Horgan; Andy Warhol; Bob Dylan, and the legions of actors, many of whom later became famous: Bernadette Peters, Fred Forest, Shirley Stoler, Neil Flanagan, Helen “The Queen of Off Off Broadway” Hanft, blonde Mari Clare Charba, Larry Burns, the entire Harris family — including George Sr., George Jr. (a.ka. Hibiscus), Fred, mother Ann (“Honeymoon Killers”), Walter Michael (“Hair”), Eloise, Jayne Anne and Mary Lou — The Screaming Violets, John Gilman, Victor LiPari, Al Pacino, Harvey Keitel, Paxton Whitehead, Ondine, Jane Lowry, Lise Beth Talbot and more.

Playwrights included H. M. Koutoukas, Lanford Wilson (15 of this Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright’s first plays were done at the Cino); William M. Hoffman (“As Is”); John Guare (“Six Degrees of Separation”); Paul Foster (“Balls”); Sam Shepard; Doric Wilson (“West Street Gang”); Tom Eyen (“Dreamgirls”); Oliver Hailey, myself and many, many others.

It should be noted here that Michael Smith ran the Cino for a time with harpsichord manufacturer Wolfgang Zuckerman, and that Charles Stanley — who famously played in drag at the Cino but wearing a beard in the H. M. Koutoukas camp chamber play “Medea in the Laundromat” — also gave it a whirl after Joe’s hara-kiri with knife in a dance-death suicide ritual on hallucinogenic drugs one night in the Caffe.

Joe died from his wounds on April 2, 1967, at St. Vincent’s Hospital. Sadly, with the passing of “The Saint of Little Theater,” the spirit of the sacred magical space went with him. Difficulties with the law and licensing had always plagued the Cino. But Joe, an Italian, seemed at home handling the police and mob interests, and the new managers were not able to cope with the explosive pressure-cooker chaos.

Doric Wilson was the first gay playwright to turn up at the Cino — in 1961 — and his plays, including “And He Made a Her,” “Babel Babel Little Tower,” “Pretty People” and “Now She Dances,” were modeled after and inspired by his hero Noel Coward. Doric in his leather phase went on to write S & M plays for The Eagle, a leather bar on West St., and finally for Tosos Theater Group, “The West Street Gang.”

In 1962, Alan Lysander James wrote and performed “The World of Oscar Wilde” at the Cino almost in the same sense that Hal Holbrook took on the persona of Mark Twain, a monologue that was first performed at Jan Wallman’s cabaret, Upstairs at the Duplex, on Grove St. One “Cino-ite” actor felt that Alan James actually thought that he had been reincarnated as “the new” Oscar Wilde.

David Starkweather came up with a play called “So Who’s Afraid of Edward Albee?” in 1963. After seeing this play at the Cino, Albee shrugged his shoulders, said nothing, and staring straight ahead, walked out of the theater in a huff.

Lanford Wilson, also a standing member of the Cino gay entourage, opened his one-act masterpiece “The Madness of Lady Bright” on May 14, 1964, starring the brilliant Neil Flanagan as the aging, tormented queen. Fred Forest, who later went on to movie stardom, appeared in this opus as a wide-eyed, innocent young man.

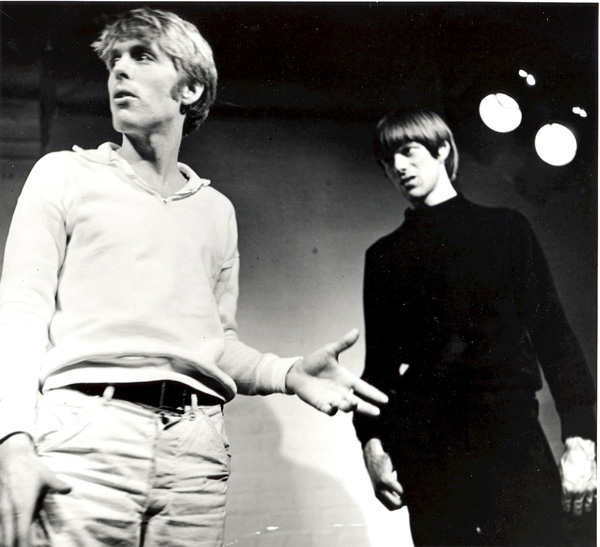

At the Cino, “gay” was simply everyday reality and not regarded as anything special or strange. My own play “The Bed” opened in June 1965, and by popular demand returned in July and September of that year. (Runs at the Cino were usually three weeks, Thursday through Sunday, with performances twice a night; sometimes on Friday and Saturday, a third late-night performance was added). Starring James Jennings and Larry Burns, “The Bed” found two young men on booze and drugs stuck in a time warp and unable to get out of bed. One of them thinks of committing suicide but instead decides simply to go out to buy cigarettes and a bottle of Coke.

“The Bed” was filmed by Andy Warhol and it is now being digitized by the Warhol Museum, a Whitney and MoMA film project. In 1966 Robert Dahdah, who had directed “The Bed,” brought “Dames at Sea or Golddiggers Afloat” to the Cino where it had a long, extended run. Dahdah discovered a 16-year-old girl named Bernadette Peters and cast her in the lead role. The camp-style 1930s Busby Berkeley musical film spoof, by George Haimsohn and Robin Miller, made theater history and turned Bernadette herself into a star. Note that a revival of “Dames at Sea” opens on Broadway at the Helen Hayes Theater this fall.

It has been put forward that H. M. “Harry” Koutoukas was the quintessential Cino playwright. He won an Obie award “for his outrageous assault on the theater” for his imaginative poetic “chamber plays” at the Caffe, featuring titles like “With Creatures Make My Way,” “Cobra Invocations,” “Tidy Passions or Kill,” “Kaleidoscope,” “Kill” and “Only A Countess May Dance When She’s Crazy.”

In 2006 there was a celebration of the Caffe Cino on Cornelia St., with a site-specific theater work, “Fragments,” featuring 1960s plays of Off Off Broadway. The incredible show (which included my own play “The Bed,” with the two actors in a giant bed being dragged up Seventh Ave. South) was produced by the innovative Peculiar Works Project, which won a 2007 Obie Award for their efforts. At one end of the blocked-off one-block-long Cornelia St., Kristen Lewis and Joel Newman tap danced numbers choreographed by Jillian Harrison from “Dames at Sea,” while in front of the Caffe (now the Po restaurant), Steven Hauck, Lars Preece and Gretchen M. Michelfeld, directed by Gabriel Shanks, enacted Lanford Wilson’s “The Madness of Lady Bright” and Evan Enderle, choreographed by Jillian Harrison, performed a memorial dance for Jonathan Torrey. At the end of the block in front of 5 Cornelia Street on the spot where dancer Fred Herko died, British actor Michael Tomlinson, portraying Herko, performed “Freddie’s Monologue” from Diane di Prima’s “Monuments,” which was the last play done at the Caffe before it closed its doors forever in March 1968.

A plaque with an image of Joe Cino affixed to the Po restaurant reads: “Joe Cino 1931-1967 – On this site in the Caffe Cino – 1958-1968 – artists brought theatre into the modern era creating Off Off Broadway and forever altering the performing arts worldwide.”

Yes, there are many ghosts on Cornelia St. and so much happened there, including possibly the birth of gay plays, and all of that has been assimilated on Broadway, in the movies, and on television.