By Jerry Tallmer

He was a large, strong, quiet man — at least in the setting where I first knew him — and I would have written large, strong, quiet, dignified man if dignified weren’t a word well-meaning white people all too easily plaster on large, strong, quiet black people they admire.

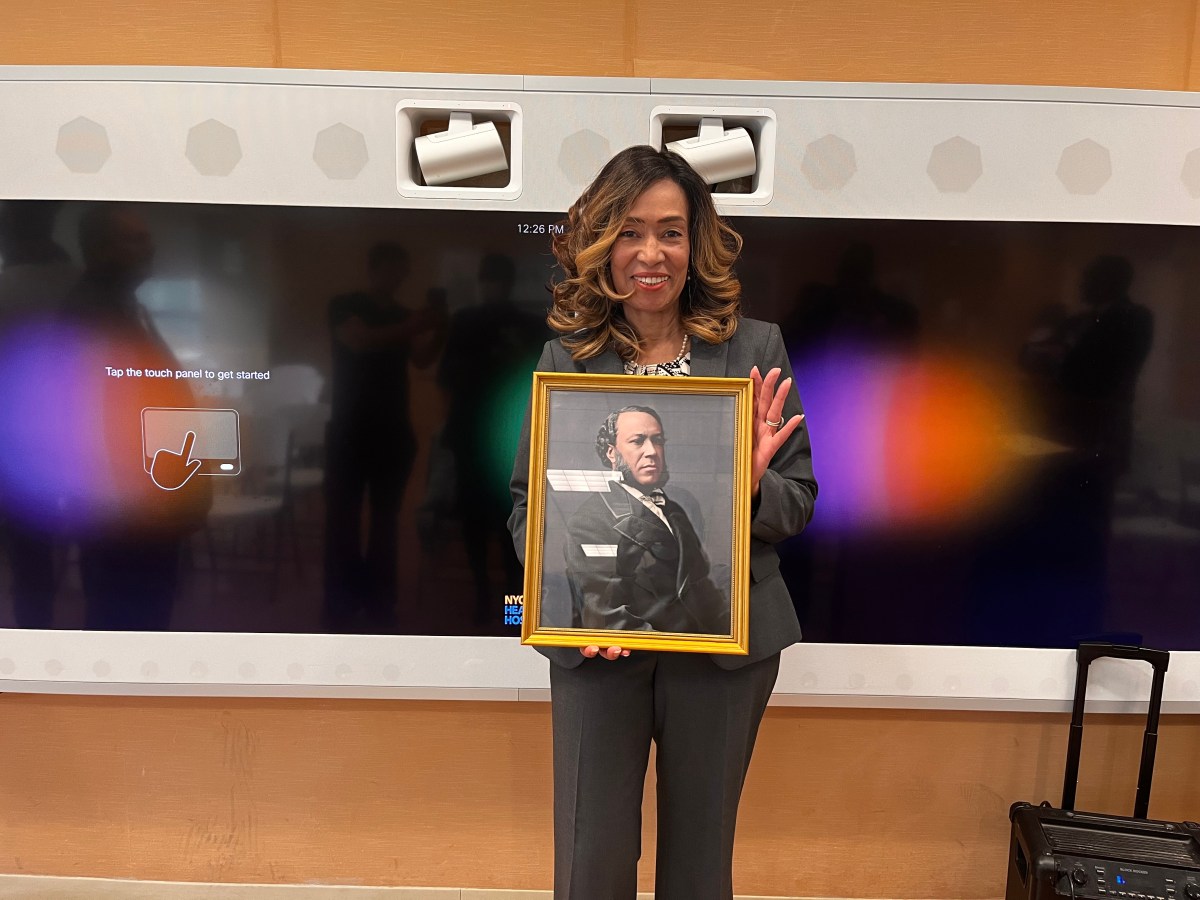

Robert Earl Jones, who died September 7 at age 96 at the Actors Fund Home in Englewood, New Jersey, never made it into the big headlines. He was more famous for his son than for himself, but if that bothered him, and it must have, the only way you might guess at it was when he on rare occasions phoned to let it be known that he himself was about to open off or on Broadway in some play.

The birthplace of The Village Voice in 1955 was a mingy 1½-room apartment one flight up at 22 Greenwich Avenue. A few desks, a few battered second-hand typewriters, a mimeograph machine, some wastebaskets and various other junk — that was it. The editor was Daniel Wolf, the publisher was Edwin C. Fancher, the associate editor was myself.

“Soon after we started,” Ed Fancher said last week — I called him when I saw the obit — “Earl came to me, introduced himself, said: ‘I’m an actor,’ and handed me a scrapbook full of his credits and writeups. ‘I live in the neighborhood,’ he said, ‘and I need a job very badly. Could I clean the office of The Village Voice?’ For several months he did that. He was a real gentleman. I felt terrible — this artist cleaning an office.” Ed laughed. “I cleaned it myself. You did too. We all did.”

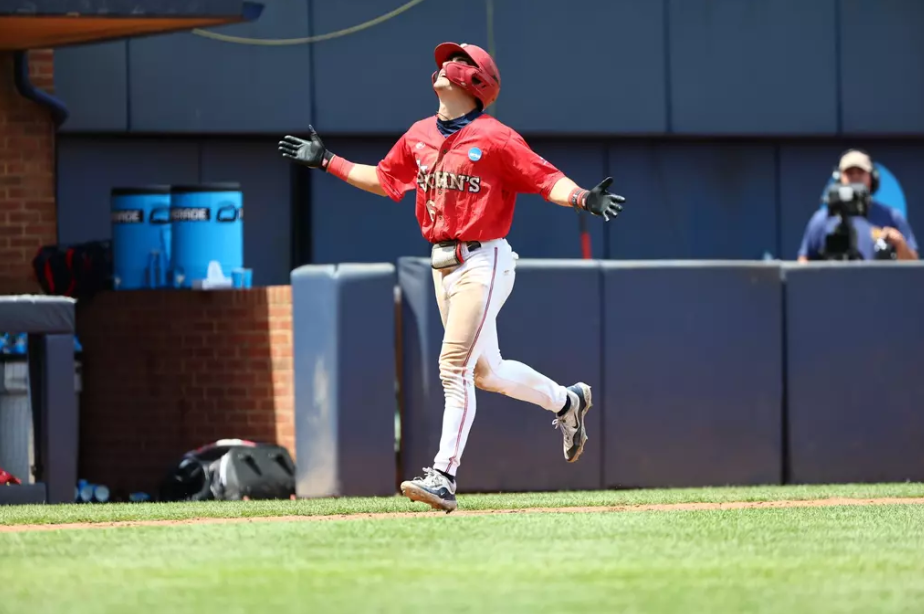

So Robert Earl Jones, blacklisted actor, former prizefighter (and Joe Louis sparring partner), former New York City Marathon runner, born Coldwater, Mississippi, February 3, 1910 or 1911, was the first janitor of The Village Voice, 1955-’56. And whenever he had to be in a show, or had a TV shot or was indisposed, the job was done — well, more or less done — by a tall, good-looking, tight-lipped young man who appeared out of nowhere and turned out, when pressed, to be Earl’s son James Earl Jones.

“And long after that,” says Ed Fancher, “I walked into a theater and there was Earl in a very good role in a movie called ‘The Sting’ [1973], all about a bunch of crooks who turn the tables on the police.”

Robert Earl Jones was in a number of good movies in his lifetime, notably “One Potato, Two Potato” (1964), as well as one very bad movie, “The Cotton Club” (1984) and in a baker’s dozen of Broadway productions as diverse as “The Hasty Heart” (1945), “Let My People Free” (1948), “More Stately Mansions” (1968), “The Gospel at Colonus” (1988) and “Mule Bone” (1991).

I too, one fine day in 1960, walked into a theater, the Cherry Lane, to review a play called “The Pretender,” by Lionel Abel — a preposterous intellectual exercise about blacks and whites that nevertheless made further manifest the brilliance of an up-and-coming talent not hitherto seen in New York.

James Earl Jones, I wrote — I omit quotation marks because this is from ultra-porous memory — is a stunning young actor but a very bad janitor.

Twenty-five years later than that, James Earl was one of the hosts at the Obie Awards. He took pains to remind the assemblage of what I had written about his janitorial talents 25 years earlier.

James Earl, I was very, very sorry to come upon that obit in The Times last night. I know you didn’t have much to do with your father until you came to New York in your 20s. I’d lost track of him these past at least 10 years. I wish I hadn’t.