Jeremy Olin remembers when he was a young beer hustler at the Fulton Fish Market in the 70s, selling brews to the workers. He befriended Carmine Russo, a mob boss at the South Street Seaport; when the beer vendor muscle came to collect a debt from him (or else), Russo offered to pay the debt.

Olin said the beer vendors quickly returned the money when they found out who his mysterious defender was; they never threatened him again.

While mobster intervention isn’t the answer to the ale house’s current woes, Olin said the institution needs someone to step up and save them.

Located on Front Street in South Street Seaport, the venerable Jeremy’s Ale House has been suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic. In good times, the bar has more than 100 people a night, enjoying music and socializing under the scores of multi-colored bras hanging from the ceiling.

But the good times may end for good after Oct. 31, Olin warned, if the city continues its prohibition on indoor dining and drinking.

Olin said Jeremy’s, and other pub he owns, are barely making ends meet, with about 50% of normal revenues. Closing for the holidays and months at a time yet again will mean the end for Jeremy’s along with most other bars and eateries in New York.

He fears only the chain restaurants with the resources to weather the pandemic storm might be the only ones left if indoor dining remains off-limits much longer.

His son, Lee, is most critical of the city for leaning on them in the midst of their financial crisis — threatening Jeremy’s with fines when people approach on foot to talk to patrons sitting outdoors on the cobblestone street that once teemed with fish and clam hucksters toiling in the summer heat, hauling chunks of ice to keep their wares cool.

“There are politicians out there that say, ‘Do this, do that, do as I do,’ but it’s easy for them because they get a paycheck so I ask how does Congress go on vacation for two weeks?” Lee Olin roared. “You a–holes should be sleeping on the damn floor until you figure out a stimulus package. No, you don’t get to go home – you got a problem here.”

The Olins have put their heart and soul into Jeremy’s, a staple in South Street for more than three decades, moving from Bridge and Front Streets more than two decades ago. They also have another bar in Freeport run by Jeremy’s son, Jason, also struggling with the pandemic.

Staying in business has been a struggle for the Olins as crisis after crisis has befallen them and many others in the city. He says every 10 years they faced adversity — the first being the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

The collapse of the Twin Towers killed many of his friends and customers and spread toxic dust around the neighborhood. Access to Lower Manhattan was restricted for weeks thereafter. Jeremy’s Ale House features a flag with the more than 2000 names of those who have died hangs from his railing.

Then, in 2012 Hurricane Sandy swept through Manhattan. The water was up to the top of the bar in the Front Street bar, its location already raised nearly four feet above the street level. But they were determined to reopen, and in weeks, they were back in operation with generators, extension cords, and after having dumped damaged fixtures and equipment.

Nothing compares, however, to the prolonged damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

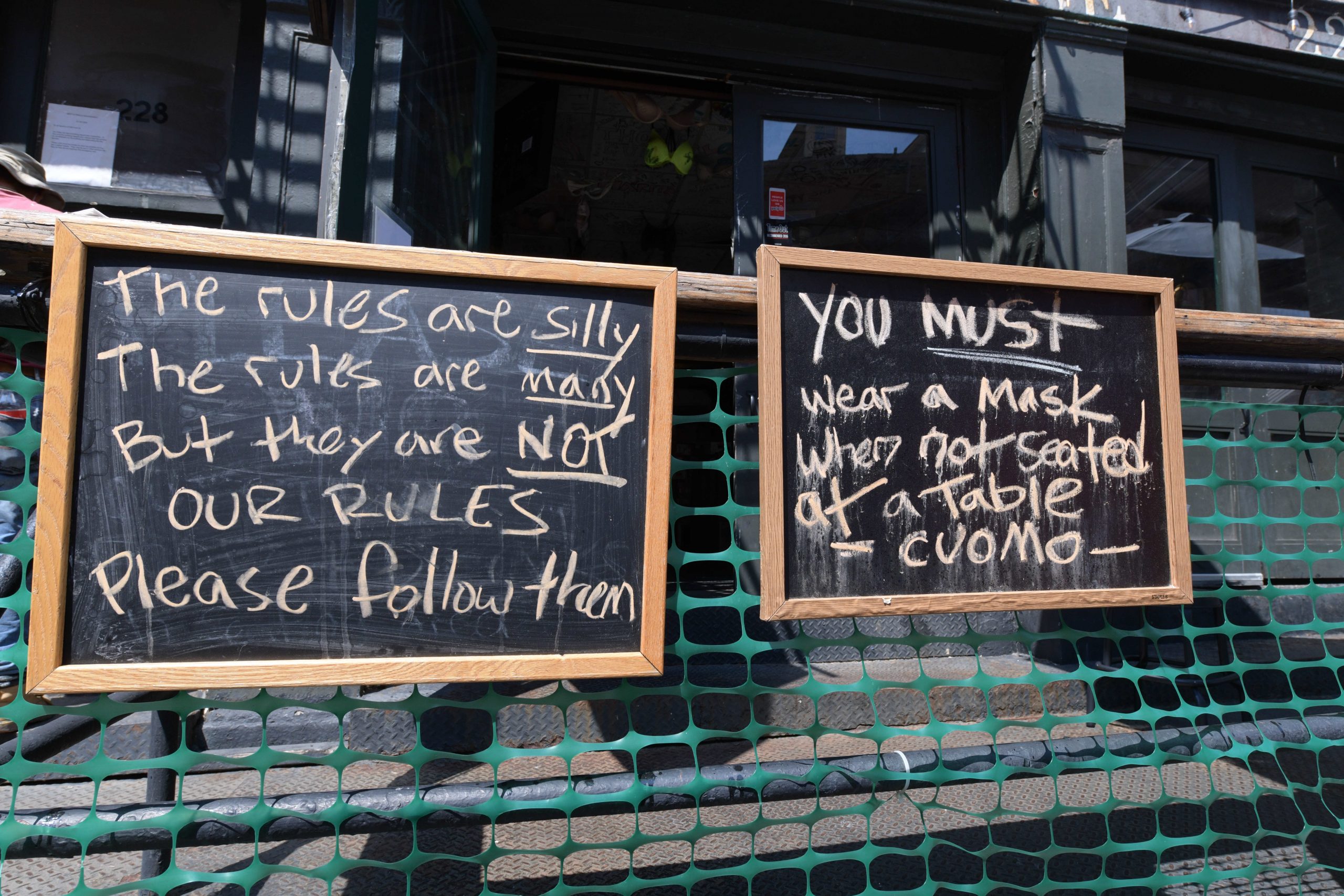

“This situation is entirely different, we can’t be open because we can only do outside – I have to yell at people all the time so we become the bad guys,” Jeremy Olin said. “I will wear a mask, if someone insists not wearing a mask, we have to ask them to leave. We can’t have people stand in the street because they will close us — yet we can’t now have as many customers. We get a $10,000 fine if we don’t enforce the rules – violations can put us out of business.”

His son believes the rules have gone too far.

“It’s all political BS, you can fly on a plane and breath that air, you can go to the gym, you can go to school. Even though you have a mask on in the plane, they recycle the air, you still breathe everyone else’s air,” Lee Olin said.

Jeremy said the Payroll Protection Program funds and EIDL loans were helpful to stay in operation and to keep people employed during the worst times. He also took a $70,000 line of credit. His landlord has also been helpful giving him a break on the rent in the worst of times.

But he said a failure to have indoor dining after Oct. 31 will mean the end. His son, who’s put his life, into the business agrees.

“This is just not a sustainable plan and if this virus is going to stay with us forever, then you have to just open up and live life the way it is,” Lee sighed. “You can’t just keep things closed, keep masks on for all eternity. If this is going to be the new norm, then we have to cut it out and say, ‘Go back to the old norm.’ It has to be temporary — it can no longer exist the way the leaders are doing it.”

Jeremy said he is not giving up, but he does expect things to go downhill.

“When I first came down here, we did a tremendous lunch business and we closed 9 p.m.,” he recalled. “Then computers and fax machines came into being and the messenger services were lost. Now people are working from home and a lot of businesses may not even return to their offices – that means we lose too.”

Lee says the virus restrictions have become political.

“Then you have these knuckleheads who will say, ‘oh, its only four months’ — we can’t afford to be closed another four months,” Lee exclaimed. “I’ve heard (Mayor) de Blasio say he doesn’t want anything open until next year. When next year? September?”

Jeremy said one neighbor, EPA Bar, was hit with multiple summonses and was forced to close. He fears a similar fate if outdoor dining isn’t extended beyond Oct. 31, and indoor dining is kept off-limits.

“If they close us up after Oct. 31 and tell us we have to be closed until we don’t know when then I think we will close. We won’t be able to survive. The landlord will say, ‘Oh, well you can go but we will have to pay for those months we were closed eventually.’ So our rent will go up by double at a time when we can’t afford for that to happen.”

This story is part of amNewYork Metro’s “Small Business Survivors” series, an ongoing look at how New York City small businesses are working to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. If you’re a small business owner surviving the pandemic, send us your story by emailing robb@amny.com.