By Aline Reynolds

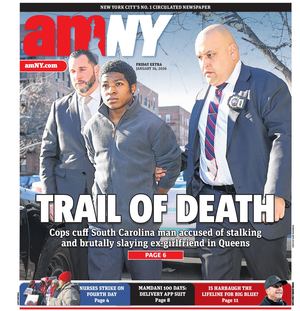

Though Lower Man-hattan is ranked as the fourth largest commercial district in the country, the neighborhood’s small businesses struggled substantially following 9/11 and the ensuing recession. Such was the message relayed by several business owners at a City Council hearing on Downtown small businesses held on Thurs., Sept. 15.

Prior to 9/11, Lower Manhattan was home to about 8,300 companies and was arguably the most famous business district in the world, noted Councilmember Margaret Chin. The 9/11 attacks damaged or destroyed 14 million square feet of office space, eliminated 650,000 jobs and disrupted or closed nearly 18,000 businesses, according to the City Council. More than 700 businesses were displaced in the former World Trade Center alone, and some 3,400 small firms in the immediate vicinity of Ground Zero lost a total of $795 million.

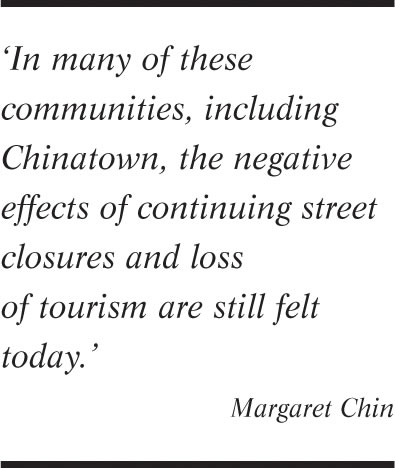

“In many of these communities, including Chinatown, the negative effects of continuing street closures and loss of tourism are still felt today,” said Chin. “For many of these owners, recovery has not been so easy, and coming [to today’s hearing] meant taking time off from work or even closing shop for the morning.”

Such was the case for Doug Smith, whose art management and framing business, “World Trade Art Gallery,” was closed for six months following 9/11. In order to keep the business alive, Smith now works six days a week and has cut his staff from seven employees to three. The business was hit hard in 2002 when customers had to pass two security checkpoints just to be able to access the store, Smith recalled.

Although a $40,000 grant from the N.Y.C. Department of Small Business Services helped Smith’s company weather the tough times, it didn’t keep revenues from slumping by 50 percent since 2000.

“The numbers for 15 years before 9/11 were great. We call it the good old days,” said Smith. “We haven’t even considered opening other shops in 10 years, whereas it was normal practice [before] to open shops every few years and sell them.”

Finding out about available grants and loans, Smith said, has been half the challenge. “It sounds so simple…but it’s not easy to know where to go,” said Smith. “The huge thing is getting the word out to individual businesses.”

U.S. Telecom, a Downtown-based computer consulting firm, has also been on a downward slope since 9/11, according to Vice President Leah Berger. Flooding in the firm’s Warren St. offices in the fall of 2001 wrecked a lot of equipment that the company lacked insurance for. Revenues have been especially sliding since the recession hit in 2008, Berger said, and a grant from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation only helped the business stay afloat, not prosper.

“The loss for us was very large, and it was all about survival,” said Berger.

The N.Y.C. Business Solutions Center, a branch of the Department of Small Business Services that testified at the hearing, assured the public that help was on the way. The center’s Lower Manhattan branch, at 79 John St., served more than 3,600 business owners and entrepreneurs Downtown and citywide in 2010 and helped to launch an estimated 60 new businesses, secure existing businesses loans and facilitate pro-bono legal advice for dozens of entrepreneurs.

Other city agencies offer companies incentives packages. The N.Y.C. Economic Development Corporation’s Lower Manhattan Energy Program, for example, provides property owners south of Murray St. with a reduction in electricity, transportation and delivery costs of up to 45 percent. The program has benefited some 1,400 office tenants and has led to savings in the amount $26 million.

The various forms of financial aid should be better publicized among the businesses, according to Gregory Carafello, former owner of a digital printing business on the 18th floor of the former South Tower. At the time, Carafello received less than 15 percent in interruption insurance claims he submitted and, once his company relocated to New Jersey, revenues dropped by 85 percent. He was forced to close up shop in 2003.

Finding out and applying for grants, Berger echoed, has been an exhausting process. “We need a 311 to help the small businesses in the area,” said Berger. “If you closed up shop and [temporarily] left the area, it took a very long time for you to figure out where these grants are, where there is help available and whom you should speak to.”

Councilmember Diana Reyna, chair of the Committee on Small Business, assured that the government agencies want to be a partner, not a hindrance, in helping the businesses recover from hardships.

“There seems to be this incentive to push in new businesses rather than [ones to] help those that have experienced the worst and encourage them to continue to stay,” Reyna said, after listening to some of the testimonies. “Perhaps more could be done for existing businesses.”

Despite the various services available, certain entrepreneurial needs are not being met, Chin agreed. “Many small business owners in Lower Manhattan…feel like they got lost in the shuffle,” she said after the hearing.

Besides better distribution of the grant and loan information, the government agencies could work to create a small business directory, promote local goods and coordinate small business showcases, she noted.

“I look forward to continuing to work with small business owners to find out what I can do to help them in moving forward,” said Chin. “It may be 10 years later, but we still have work to do.”