Photographer Martha Cooper has documented some of New York City’s most critical cultural movements in the last half century.

Cooper has chronicled the lives of threadbare children playing amongst the ruins of a poverty-stricken Bronx in the 1970s before following graffiti artists who made the metropolis’ subway train their own moving canvases. She also made her name by helping capture the birth of the breakdancing scene, all with her unique eye and through her lens.

However, it wasn’t an easy journey. Cooper entered a field dominated by her male counterparts, still she persisted, becoming one of the first female staff photographers at the New York Post.

Now, on the verge of 80, she both continues to look back over her storied career while still traveling the world looking for her next project.

On July 21, throngs of New Yorkers packed into seats at the International Center of Photography — a prestigious photo gallery that celebrates the power of the image and is currently showcasing the works of William Klein — on Essex Street to watch a documentary based on Cooper’s life: “Martha, A Picture Story.”

The film premiered at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival, just prior to the surge of COVID-19 in New York. The pandemic took a toll on the film, preventing it from being released on a larger scale.

“I felt very sad for the filmmaker, Selina, that the film missed a lot of film festivals that it would have been shown at, which is kind of too bad. She worked really hard on it,” Cooper told amNewYork Metro prior to the screening.

Despite the hardships wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, Cooper didn’t slow down. She spent time delving deep into her vast back catalog of images to compile a new book of previously unpublished work named Spray Nation, and in the process discovered photographs she forgot she had.

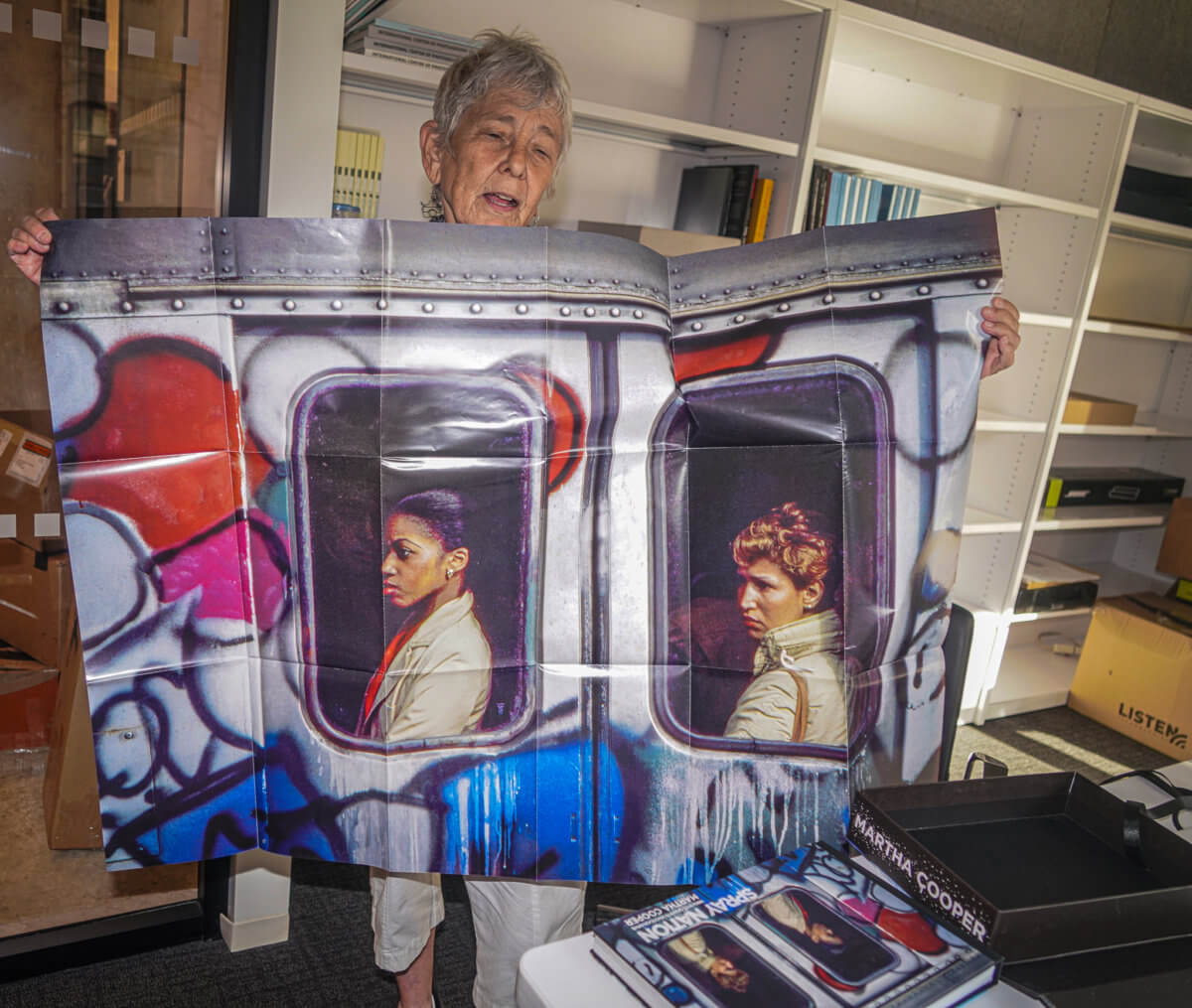

“I had no idea. I would never have gone back, as far as I was concerned that was like over. So, it was fun, for example the European edition has this one on the cover,” Cooper said pointing to the back of the book. “Which I also liked, but I actually like these two women in the train better,” she continued, unraveling a large poster.

It is evident that no matter how much time passes, the photographer remains just as committed and passionate about her work as she was 30 years prior. In Cooper’s mind, her career wasn’t a story of perfect stills. She achieved her life-long dream of working for National Geographic, but it wasn’t quite what she had hoped for.

“I got the cover, but look, it’s an article about pollen. So, my dream had been to work for National Geographic and my idea was, I’m going to travel all over the world. Let’s take these wonderful pictures and what do I do? I get a story about pollen. In fact, I’m living what I thought I wanted to do, but not for National Geographic. It turned out that I really wasn’t that kind of photographer. I wasn’t interested in this kind of story and so I am traveling all over the world. I’m taking pictures of graffiti and street art. I got what I wanted, but not in the way that I thought that it was going to happen. I’m telling you this because I think it’s a lesson for photographers to concentrate on the things that they’re good at and that they really like,” Cooper said.

With pandemic restrictions currently eased, Cooper is capturing moments both in New York and across the world. Most recently she photographed the Pride Parade outside the StoneWall Inn and street art in the Congo in Africa, so the question remains: what will be her next big project?

“I’m always keeping my eyes open. I don’t really know what the next thing is gonna be. But I hope that something will capture my attention and I’ll go after it. Now I’m spending more time organizing my files than I am in taking more pictures. I would say I’m just trying to get everything in a way that could in fact, be left and it’d be, you know, part of history. I think this [Graffiti] is a huge art movement, it’s grown into this enormous art movement. I don’t think it’s as well understood as it could be. There are some amazing graffiti writers out there and you’re not going to find any pieces of graffiti in MOMA. For example, MOMA is a Museum of Contemporary Art. Why haven’t contemporary art museums embraced some of this amazing art? I think it’s gonna happen, and so I want to have my section of history to be organized in a way that people will be able to do research,” Cooper said.

Viewers at ICP gave the screening a rousing round of applause and even stuck around to view the William Klein exhibit which runs through Sept. 12. Spray Nation is currently available as a boxset, which includes post cards and a poster. The standalone hard cover book will be released on Sept. 6.