[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

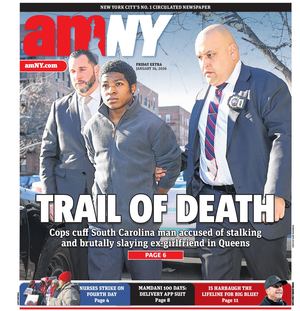

- Sarah Henry, deputy director of the Museum of the City of New York and curator of the Titanic exhibit at the South Street Seaport Museum, looks at a photo in the exhibit of Jack Phillips, the Marconi wireless operator who sent increasingly desperate messages to neighboring ships as the Titanic foundered.

BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | At the entrance to the South Street Seaport Museum’s Melville Gallery, a display of clothing reminds visitors to “Titanic at 100: Myth and Memory” that the exhibit is about real people who were aboard the ship on April 15, 1912 when it sank after hitting an iceberg.

A handsome outfit for Col. John Jacob Astor IV, reputedly the richest man in the world, is there. So is one for philanthropist Margaret Brown, who became known as “the unsinkable Molly Brown,” and Benjamin Guggenheim, who changed into evening clothes so that he could “die like a gentleman.” J. Bruce Ismay, chairman and managing director of the White Star Line, is represented by a posh coat. The plain clothing of an unnamed steerage passenger shows the Titanic’s distinctions of class and wealth.

The clothing was created for a recent television mini-series about the Titanic but there are numerous objects in the exhibit that really are from a hundred years ago — a gold ring set with a small diamond that was a 21st birthday gift to a man who drowned, a cribbage board made of wood from the ship, a commemorative hatband, letters from Thomas Andrews, the father of the Titanic’s builder, Thomas Andrews, Jr., referring to “our dear lost son.” And there are drawings and deck plans of the ship, a large model and many photos including one wall-size picture of an iceberg taken by someone aboard the Carpathia, the ship that rescued the Titanic survivors, a few hours after the collision.

But some of the most evocative items are the telegrams sent to and from the Titanic by Marconi operators. “The Marconi messages give you an almost minute by minute account of what was happening, and not just what was happening aboard Titanic but on the other ships that were in the area,” said Greg Dietrich, a marine historian, who consulted on the exhibit. “Most of the messages are between Titanic and her sister ship Olympic, which was 500 miles away. And then you have the silence from Titanic and the other ships radioing to each other, ‘Have you heard from Titanic?’ And you realize by then she was gone. It took around three hours for her to sink from the time she hit the iceberg.”

Sarah Henry, deputy director of the Museum of the City of New York and curator of the exhibit, compared the panicked search for information following the sinking to what occurred on 9/11 after the destruction of the World Trade Center.

“You can see it playing out, the confusion, the lack of information, and yet [there is] an incredible amount of information compared with what would have been available a few short years earlier because of the advent and spread of the wireless system,” said Henry. “I think people must have been amazed that they could follow the news as well as they did.”

One of the photos in the exhibit shows a crowd gathered outside 1 Park Place, the office of the newspaper New York American, as a man painted a bulletin board with the latest update. Crowds gathered outside of all the New York City newspapers as they did outside the office of the White Star Line at 9 Broadway. Reproductions of some of the newspapers are in the exhibit, and visitors can leaf through them to see how news of the tragedy emerged.

There are also posters and props from the many movies that have been made about the Titanic, and an interactive reproduction of the ship that was used to create the most recent iteration of the Titanic story, the four-part television mini-series that aired this month.

“Titanic at 100: Myth and Memory” is at the South Street Seaport Museum’s Melville Gallery, 213 Water St. The museum is open Wednesday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. The main galleries of the museum are at 12 Fulton St. Through April 30, admission is $5, and children under 9 can enter for free. As of May 1, adult admission will be $10.