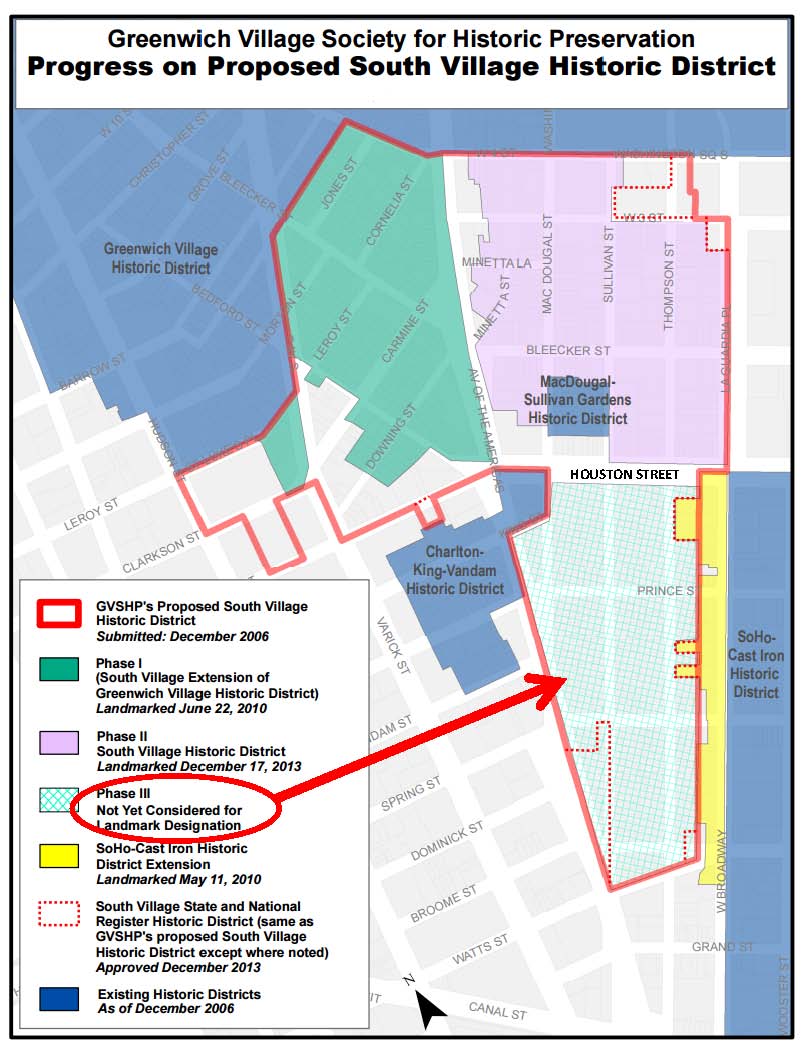

BY DENNIS LYNCH | The Landmarks Preservation Commission heard its last round of remarks from the public concerning the proposed Sullivan-Thompson Historic District — a.k.a. phase three of the South Village Historic District — on Nov. 29. The agency’s 11 commissioners could vote as soon as Dec. 13 whether to landmark the roughly 10-block area bounded by Broadway and Sixth Ave. and W. Houston and Canal Sts.

The majority of the roughly three-dozen residents, property owners, business owners and other stakeholders that testified supported the district’s designation. The area contains buildings from as early as the turn of the 19th century, but also includes numerous tenement buildings where immigrants from around the world and particularly Europe first lived.

The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation has spearheaded the designation campaign over the last decade. So far, the first two-thirds of the proposed area has been landmarked. G.V.S.H.P. Executive Director Andrew Berman evoked the neighborhood’s immigrant connection in his testimony.

“There are few parts of New York where one can walk down streets and see what an immigrant community at the turn of the last century, during the last great wave of immigration to New York City, looked like,” Berman said. He added that many of the tenement buildings still feature their original architectural details.

Many supporters testified on the need to protect the South Village’s neighborhood character in the face of encroaching development projects in surrounding areas. Councilmember Corey Johnson and representatives from Assemblymember Deborah Glick and Borough President Gale Brewer spoke in support of the landmarking.

A handful of people spoke against the designation. Two building owners told the commission that they would not be able to afford to maintain their buildings or upgrade them to make a profit if they were landmarked.

The owners of landmarked buildings have to present any alteration plans to the commission, which in most cases requires hiring a lawyer, and the commissioners can reject any alteration if they feel it dilutes the historic quality of the building. That usually means spending more money on historically appropriate materials.

Steven Hamilton, who owns and lives at 198 Sixth Ave., asked that the commission to remove his block, between Prince and Spring Sts., but landmark the rest of the district. Hamilton and his wife invest a part of their profits from rent on upgrading the building, which he claimed is not historically significant. To use more expensive materials would make those upgrades cost-prohibitive, he maintained.

“I’ve talked to different people who have landmarked buildings, who have told me that it significantly increased the cost of any sort of treatment they want to do, so that would be a burden on us,” he testified. “We barely get by as it is. We manage through rents to do $5,000 or $6,000 worth of improvements a year. That’s about how much we would spend on legal fees — we’d just not be able to do anything.”

Hamilton added that he felt left out of the conversation and that proponents of the landmarking had not taken into account the new development that took place on his block over the last half decade.

It is not unusual for some property owners to oppose landmarking over concerns of the cost of maintenance and the effect it can have on property values. However, the commission does not require that all property owners support a designation.

The N.Y.U. Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy found in 2014 that New York City properties in historic districts and those calendared for potential designation sell for 20 percent more than those outside historic districts — except in Manhattan.

According to the Furman Center study, landmarking boosts the values of existing buildings, but the value of the land under most buildings in Manhattan contributes a more significant share of the overall property value than it does in outer boroughs, where the existing structure on the property contributes more heavily to the property value.

The “hit to land values outweighs the boost to structure values,” the study found.

The city’s Independent Budget Office, however, found in a study of historic district properties between 1975 and 2002 that those properties increased in price at a “slightly greater rate” than those outside districts. But the I.B.O. report said there was not enough evidence to conclude that historic district designation caused that increase.

But G.V.S.H.P.’s Berman said that designating a district will be a financial benefit over time because it protects property owners from large-scale construction that could hurt their property values.

“Part of what you’re benefiting from is you share in perpetuity this special and distinctive neighborhood character,” Berman explained. “There is not a risk of that disappearing or being ruined by some insensitive, out-of-context development on the block.”

Landmarks law also has a built-in “hardship provision” that obligates the commission to remove alteration restrictions on a building if the owner can prove that he or she cannot make a profit or do what is necessary to maintain the building, Berman added. Those cases are rare and usually end with a full demolition of a particular building.

L.P.C. will reconvene on the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District on Dec. 13. Berman said he is cautiously optimistic that they will vote on the designation that day, because a few days later the full City Council will vote whether to allow a transfer of air rights from Pier 40 across the West Side Highway to a site for a massive development project at what is now the St. John’s Center at 550 Washington St. The developers are also seeking a residential rezoning for the site, which is just a few blocks away from the edge of the proposed historic district.

Some believe that landmarking the final unprotected section of the South Village is the only way to check what they believe will be a wave of development that the Hudson Square megaproject could spur.