BY SAM SPOKONY

Documentary drama reveals the troubled world of student veterans

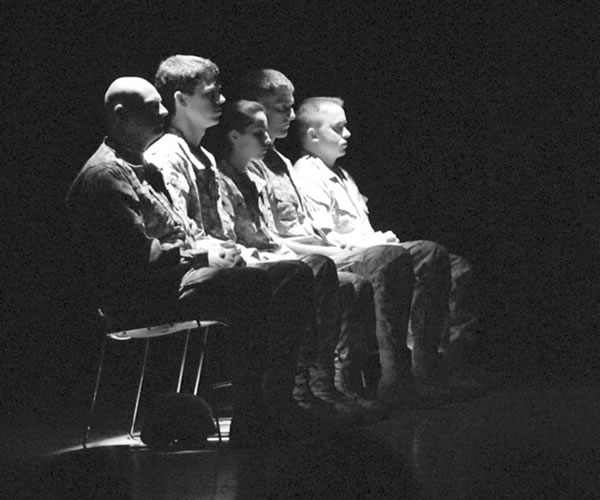

“civilian”

FringeNYC shows run through Aug. 28, 2pm-midnight weekdays and noon-midnight on weekends. Tickets: $15 in advance at FringeNYC.org or 866-468-7619; $18 at the door. Discount passes for multiple shows. For show dates, times and venue info, visit FringeNYC.org.

The war in Afghanistan — now the longest armed conflict in American history — has had an indirect effect an every part of American life. Nowhere is that more clear than within the world of college-aged soldiers, who, after completing their service and returning home, are forced to adjust to an academic atmosphere that is often more foreign to them than the deserts of the Middle East. The documentary drama “civilian,” which grew out of a series of interviews with student veterans (at the University of Kentucky’s Center for Oral History), cuts to the heart of these tensions with intelligence, respect and incredible strength.

Playwright and director Herman Daniel Farrell III created “civilian” from a virtually verbatim reading of those transcripts. That format — in which a professor conducts the interviews and informs the student veterans of the their inclusion in an upcoming play — allows the audience to see the work as it developed (even as they are being introduced to the soldiers).

When former Marine Nathan Noble (Kevin Sullivan) learns of the play, he says adamantly that there should be “no interpretation” to warp the experiences or words of his peers. That Farrell not only follows Noble’s advice, but also includes his statement in the performance itself, is a testament to the veracity of the script (and the success of his vision).

The veterans’ most gory battlefield experiences are presented alongside their equally striking recollections of anxiety, disillusionment and misunderstanding upon entering college. As a result, we learn things about American soldiers that aren’t talked about in newspaper reports or television specials — and that is the greatest value of “civilian.” When the masks we have forced upon them are stripped away, and when they no longer have to bear their burdens in silence, we are forced to reevaluate all the pre-conceived notions we have about our young veterans.

Also important to its success is the fact that “civilian” does not defend or fetishize war, or the heroic image of the American soldier. Farrell, by drawing directly from his sources, presents them not as we would like to see them — and not as we might have ever seen them portrayed — but simply as they are.