A pizza place, a Famous Brands department store, a liquor store, a Chinese restaurant and a Sherwin-Williams Paints store line the Queens street leading to a small fruit and vegetable stand that sits outside of the construction zone where a Key Food Supermarket used to be. Ali Meye sells guava, asparagus, oranges, apples, pineapple, avocado, cucumbers and cauliflower from the stand.

The Key Food located at 22-15 31st St. closed at the beginning of October 2020 after serving the Astoria neighborhood for over 20 years. Now, the site is a fenced-off construction zone where a new Target department store will stand by 2023.

In the years leading up to the pandemic, supermarkets throughout New York City were already closing due to rent increases, narrow profit margins, increased competition with drugstores and online grocers and larger developments moving in and pushing smaller stores out.

Owner of Gristedes Supermarkets and Red Apple Group CEO and chairman John Catsimatidis, who has owned and operated supermarkets across the city for nearly 50 years, said the only reason Gristedes and D’Agostino have survived is because Red Apple Group is funding them.

D’Agostino, which opened in 1932, is down to 11 locations from a peak of 26 in 1996, and Gristedes, which opened in 1888, is down to 30 locations when there were once over 100 Gristedes stores across the city.

Now, in the wake of the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic, more small business and grocery store owners struggle to pay rent, and with more people opting to order food online, profit margins continue to shrink. The disappearance of local supermarkets is causing food deserts to expand across the city, and in areas where larger chains replace locally owned stores, some workers are left working for non-union companies that pay minimum wage. Often, these larger grocery stores and/or retailers do not offer products that reflect the needs of the community and raise issues of affordability.

How closures affect communities

The Key Food at 22-15 31st St, where the Target is now being built, was down the street from the Astoria-Ditmars Boulevard train station with access to the Q, N and W trains.

One 37th street resident said the closure of Key Food was a “terrible” thing because they had good stuff and it was easy to hop off the train, go shopping and go home and the market had a great selection of fresh food.

Now, some residents have to shop at multiple places to get everything they used to buy at Key Food.

Jose T., an Astoria resident, said losing Key Food was “brutal.” Instead of having one grocery stop, he has three: Lidl, an organic vegetable place close to where Key Food used to be and Trade Fair on Ditmars Boulevard. Sometimes he shops in Queens’ ChinaTown, but that can be expensive, he said.

“Lots of people shopped there and having it close down closed off the primary source of groceries for a lot of people,” Jose said.

The coming Target will likely offer less products that reflect the community, as many large, corporate companies often do not cater to specific community needs.

“Key Food was really a place where everyone felt welcome. The staff at the Key Food knew so many of the members and what they liked and had developed and nourished these relationships over the years,” said New York State Senator Jessica Ramos who is the chair of committee on labor, representing city district 13.

The closure also affects area workers.

Key Food Stores Co-op, Inc. is a cooperative of independently owned supermarkets. The Key Food at 22-15 31st St was unionized. Target is a non-union company meaning employees do not have as powerful a voice on the job, and many employees will only make minimum wage. When jobs are non-union, there is a greater turnover over-time among staff, causing inconsistency in service and decreased service quality, Ramos said.

“Ultimately Target, like the Walmart model, really destroys communities. And I haven’t only opposed and fought that Target coming to that space on 31st Street, but also the one that has now opened on 82nd Street, which was the first Target that was proposed in my district,” Ramos said.

The struggle to compete

Locally owned supermarkets struggle to compete with larger chains because they do not have the necessary access to capital. This leaves storefronts vacant.

“I have seen it with my own eyes in my own neighborhood of Brooklyn, and it’s a problem nationwide,” said Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America, an NYC based nonprofit group working to enact the policies and programs needed to end domestic hunger and ensure that all Americans have sufficient access to nutritious food. “Brick and mortar retailers, not just food stores, are all in trouble. Rent is so high and the profit margins in the supermarket industry are so small it has taken a toll.”

Not only do companies, like Target, have the capital to afford higher rent, but also their contracts often include lease riders that prevent landlords from renting any adjacent space to any possible competing small businesses.

This leaves consumers at a disadvantage because they have no choice but to shop there.

“I find that the city has poor economic policy that really dissuades landlords from offering affordable rents to local commercial merchants, namely business improvement districts,” Ramos said.

Smaller supermarkets also struggle to compete with online grocers, grocery delivery apps and drugstore chains that have expanded to include grocery items.

“Drugstores, online grocery stores, non-union operations— a little bit of everything— everybody has attacked the traditional supermarkets that fed the customers in New York for the last 50 years,” Catsimatidis said. “I would say, down deep inside, it’s an inconvenience for the consumer and the consumer is not being served properly in the New York area.”

Expansion of food deserts

The loss of supermarkets in neighborhoods has caused food deserts to expand.

The USDA defines a food desert as an area with limited access to healthy food. In urban areas, an area is deemed a food desert when a significant share of the population is greater than a 0.5 mile or 1 mile away from the nearest supermarket, supercenter or large grocery store.

Berg said the official USDA definition does not work well for New York City because New York is a pedestrian city, and 1 mile means walking 20 blocks. Experts in the New York City food access field recognize areas a quarter of a mile (about four to five blocks) away from a large grocery store as an area with low food access.

In a highly pedestrian city, like New York, people also have to consider physical barriers to reaching stores like highways blocking pedestrian paths, the safety of a store location and if the store is in a convenient area near other retailers, schools, work and transit hubs.

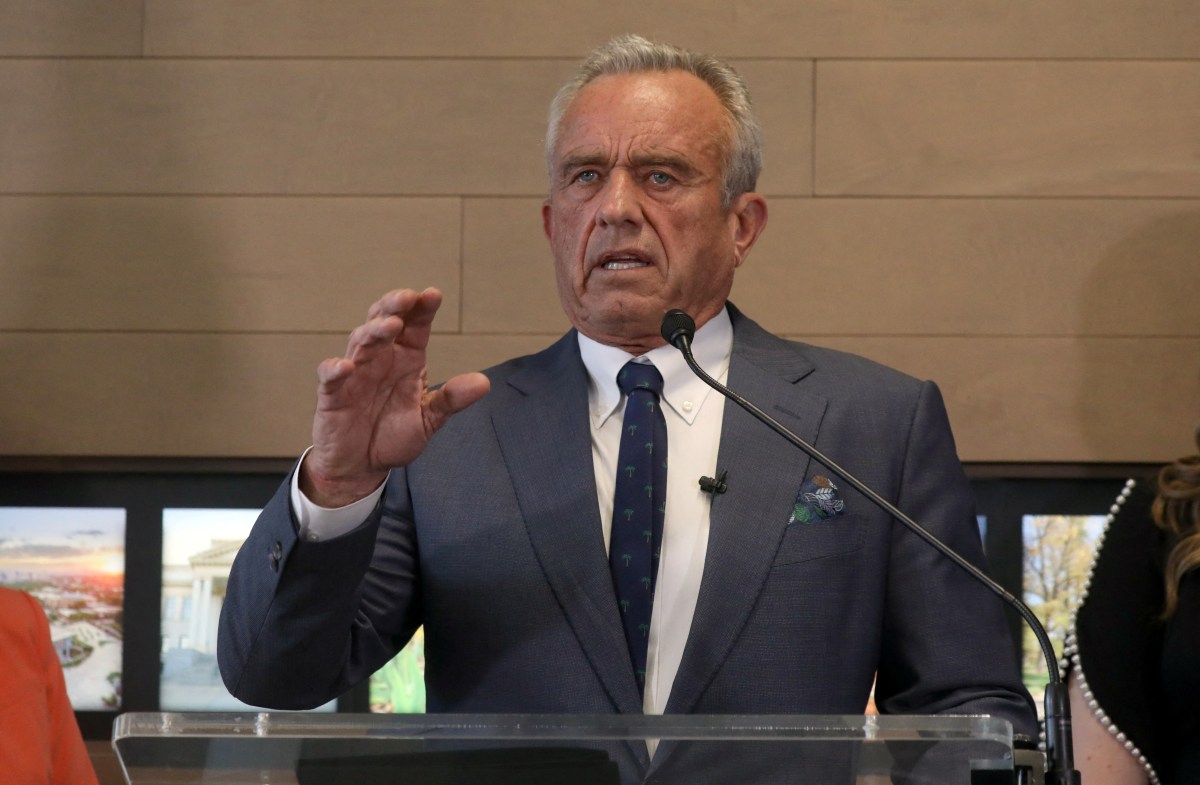

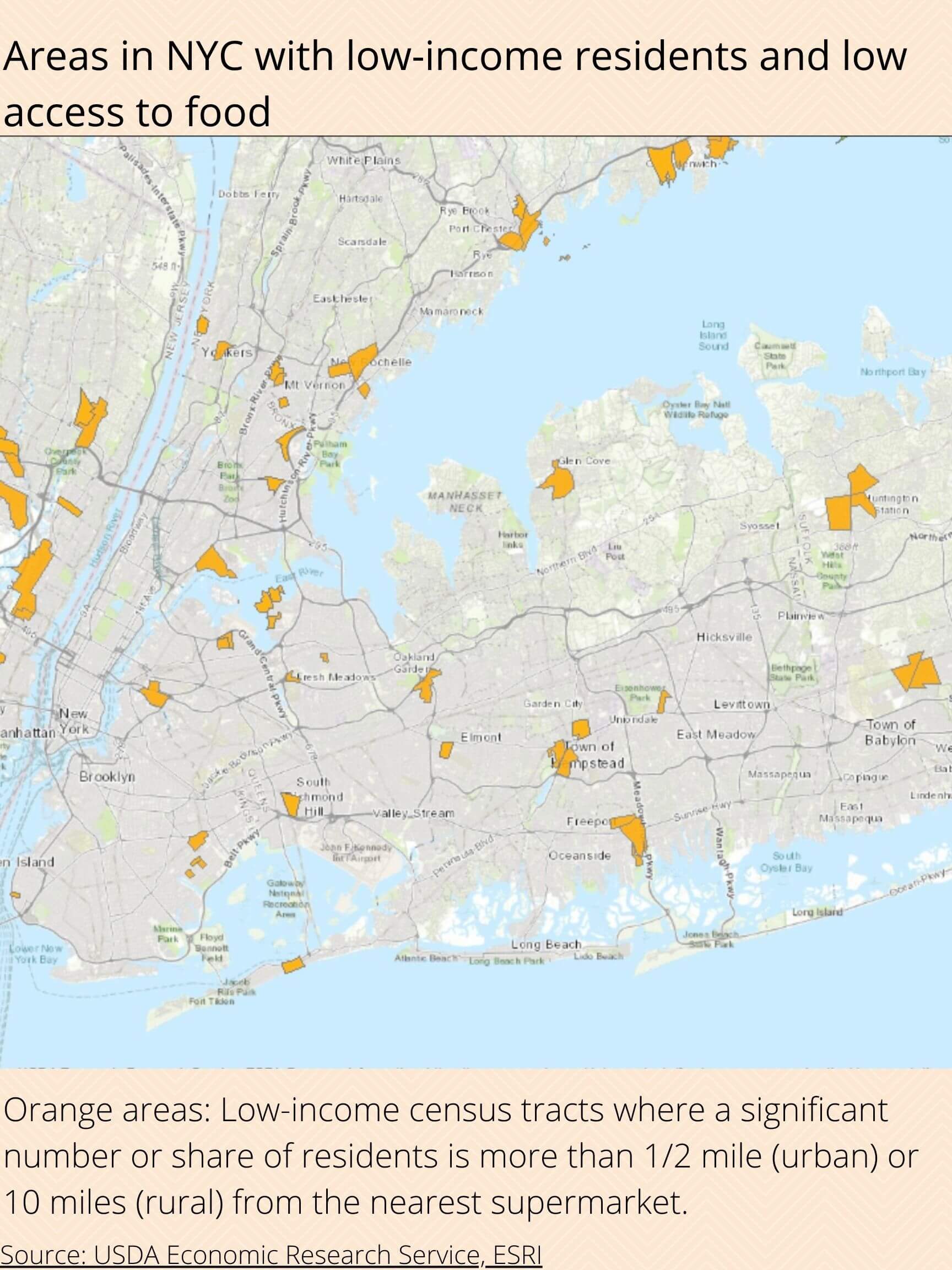

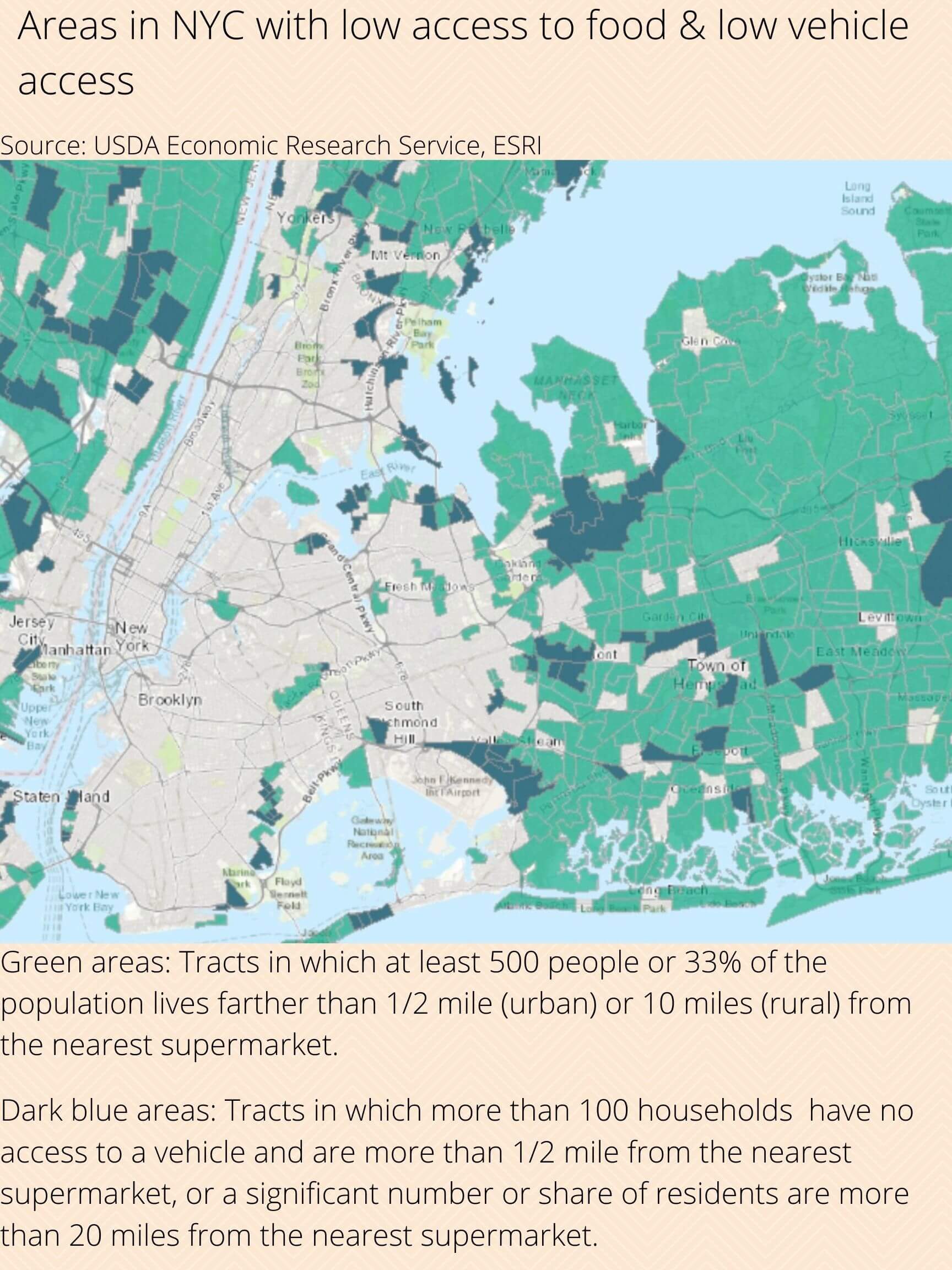

The USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas measures food access by census tracts, small, relatively permanent statistical subdivisions of a county or equivalent entity. Kings, Queens and Bronx counties all had several low-income census tracts where a significant number or share of residents was more than a 0.5 mile from the nearest supermarket in 2019, according to data from the United State Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service’s Food Access Research Atlas.

Excluding income, the same counties also had several census tracts in 2019 with at least 500 people or 33% of the population living farther than a 0.5 mile from the nearest supermarket.

Many tracts in these counties had more than 100 households located a 0.5 mile from the nearest supermarket with no access to a vehicle or a significant number or share of residents living more than 20 miles from the nearest supermarket in 2019.

The Associated Supermarket on Nostrand Avenue near Empire Boulevard in Crown Heights, Brooklyn (Kings County) closed its doors at the end of July 2021, nearly turning the neighborhood into a food desert. Now, the nearest supermarket is Empire Kosher Supermarket .4 miles away.

The supermarket served the largely working class neighborhood, where 64.3% of the population is Black (non-Hispanic) and 40.2% of the population is made up of foreign born residents, for five decades.

Its demolition, ahead of a construction project by Midwood Investment & Development, has caused concern for many area residents.

Residents said they worry about the lack of affordable, accessible and healthy food in the area due to the closure, according to a spokesperson from the office of Brooklyn borough president.

Midwood Investment & Development said a grocery store will eventually return on the ground floor of the planned residential development.

But this could take years.

“The recent closures of grocery stores across our borough has been part of a broader trend across the city for a number of years, particularly in areas that otherwise lack access to fresh produce, which has been deeply concerning,” said Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams in an email.

The Brooklyn Borough President’s office worked with GrowNYC to fund a farmstand outside the Associated Supermarket on Nostrand Avenue in the wake of its closure, in partnership with local elected leaders.

Barriers to access

Even in areas with supermarkets, barriers to access still persist.

The Economic Research Service’s Food Access Research Atlas showed a significant number of low income census tracts (areas with a poverty rate of 20% or higher, or tracts with a median family income less than 80% of median family income for the state or metropolitan area) that had adequate access to food.

“The biggest issue to access is money,” Berg said. There is a Whole Foods between a low income and non-low income neighborhood in Brooklyn not far from public housing, Berg said. But for some people, shopping at Whole Foods would mean spending their whole paycheck.

“And just having something there, if it’s unaffordable it doesn’t have that much meaning,” Berg said.

Sabrina Baronberg, who has spent years working in strategic planning and program planning around food access and food insecurity, said there are some people who have a supermarket down the block from them, but they’re willing to travel an hour on the bus to get to a better supermarket if it’s more affordable for them or more worth it.

“It’s really important to not just think about the number of supermarkets and look at them on a map, but really think about, ‘What are the options that are available in these different food retail outlets, and are people really going to them?’” Baronberg said.

Working toward solutions

In May, 2021, former City Planning Commission Chair Marisa Lago announced the start of public review for an update and expansion of the Food Retail Expansion to Support Health program that works to provide fresh food options for New Yorkers. The proposal would expand the FRESH zoning incentive to 11 additional lower-income Community Districts throughout the City, on top of the 19 districts where it already applies, bringing more green grocers to underserved neighborhoods.

“No New Yorker should have difficulty finding fresh food for themselves and their families,” said Joe Marvilli with the NYC Department of City Planning in an email. “Through our proposed expansion of the FRESH program, we’ll make it easier than ever for grocery stores to open and stay open in lower-income communities, greatly improving health and quality-of-life for residents in these neighborhoods.”

In October 2021, the proposed expansion of the FRESH program was approved unanimously by the City Planning Commission and is now before the city council for review.

“The city is really making an effort to support and enable supermarkets to survive through programs like that,” said Baronberg about the FRESH program.