By Lawrence Lerner

Photo courtesy of Battman Studios The re-created Levine kitchen at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum

Ruth Abram, president of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, remembers the day she and Anita Jacobson, the museum’s co-founder, struck gold. The pair had been looking for a preserved pre-old law tenement on the Lower East Side for two years before stumbling onto a gem at 97 Orchard St. in 1988.

“We had all but given up on finding one,” said Abram, explaining that the “old law,” the city’s first effort to regulate tenement construction, passed in 1879, required airshafts in tenements. “Most of the older pre-old law buildings had been tampered with by the time we began looking for a site for the museum.”

Their fortunes changed when Jacobson spotted a “For Rent” sign at 97 Orchard St. and contacted the landlord, Barbara Halpern, for a tour. According to Abram, Jacobson asked where the bathroom was, and when Halpern took her to the hallway to show her the water closet, she knew from her research that she had found their building.

“When Anita explained to the landlord what we were trying to do, the landlord said, ‘You’re home,’ ” said Abram, who got a very excited call from Jacobson to meet her at the building. “When I got there and first walked into the dark, narrow hallway, I felt like I was standing on hallowed ground,” she said, explaining that the worn, peeling interior had remained untouched since the 1930s.

With that stroke of luck, one of the country’s best-known living-history museums was founded, with the express purpose of promoting understanding and tolerance of immigrants and helping newcomers establish roots in America. The Tenement Museum does this by interpreting the urban immigrant experience through the lives of families that lived at 97 Orchard St., and linking those histories to pressing contemporary immigration issues, such as affordable housing and sanitary living conditions, assimilation, labor and social and economic justice.

For Abram and Jacobson, it was slow going at first. Only the two basement-level storefronts of the five-story tenement were in use when they discovered it. They moved into one in 1988, then the other the following year, producing historical theater and a neighborhood walking tour while taking prospective donors through the upper floors, which housed the uninhabited apartments that would become the museum’s centerpiece.

Built in 1863, with 20 apartments measuring approximately 325 square feet each and no indoor plumbing, ventilation or light, 97 Orchard St. was home to an estimated 7,000 immigrants from more than 20 countries before the owner closed it as a residence in 1935 rather than abide by a new city ordinance requiring that the hallways and stairwells be fireproofed.

According to Abram, it took five years to convince Halpern to let the museum purchase the building, and another three to persuade donors to start giving.

“We had paid tribute to both the rural pioneer and farmer experiences in this country, but never before had we memorialized the urban working class and immigrant poor,” said Abram. “A tenement museum was anathema at the time. People were not sure what to make of us.”

That began to change in 1994, when the first of what is now five restored apartments depicting the lives of families who inhabited them opened to the public. Currently, visitors can learn about a German Jewish family, the Gumpertzes, who survived the Great Panic of 1874; the Levines and Rogarshevskys, Eastern European families who worked in the area’s burgeoning garment industry around the turn of the century and during World War I; the Sephardic Jewish Confino family, who emigrated from Greece; and the Baldizzis, Italians from Sicily who were some of the building’s last Depression-era residents.

Recognition came to the museum four years later when it was designated a national historic site, and its growth continued unabated as locals and tourists came to understand its importance among historic sites. Last year, the museum hosted nearly 125,000 visitors from all 50 states and more than 30 countries. And though it now has 40 full-time staff along with part-time educators and volunteers and an annual budget of nearly $5 million, the museum regularly turns away people hoping to take its hour-long apartment tours, which are given every 20 minutes, seven days a week.

To meet the demand, the museum is launching two new exhibits: a re-creation of the fourth-floor apartment inhabited by an Irish immigrant family in 1869, slated to open next spring, and a re-creation of a German saloon that occupied one of the basement storefronts from 1864 to 1886, which will open in 2009. The museum received $1 million from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation for the projects in March, part of $27.4 million in grants the L.M.D.C. awarded to 63 Downtown cultural institutions.

Steve Long, the Tenement Museum’s president of collections and education, says the exhibits fill important historical gaps.

“The Irish were an important immigrant community in New York City, and the family we’re depicting, the Moores, moved four times between 1865 and 1870, which reflects the transience of many immigrant families who moved through this neighborhood,” he said. “They also had eight kids, with half of them succumbing to disease before they were a year old.”

According to Long, the saloon, opened by German immigrant John Schneider, tells another important story, since it was a hotbed of political activity in its day.

“The German Reform Club, of which Schneider was a member, and the 8th Assembly District both held meetings in the space,” he explained. “Saloons were a central community center for German immigrants on the Lower East Side.”

In addition to apartment tours, the Tenement Museum produces an award-winning Web site featuring virtual installations by contemporary immigrant artists. It also offers language and civics classes to new immigrants, nearly 1,400 of them last year alone.

Making the connection between generations of immigrants was central to Abram’s conception of the Tenement Museum.

“History has a purpose,” she said. “The point of understanding the story is to relate the past to contemporary issues and help people in the present. As a famous Sierra Leone history keeper says: ‘What’s the point of telling a story if it doesn’t help people transcend?’”

That spirit led the Tenement Museum to team up with other area preservation organizations early this year to form the Lower East Side Preservation Coalition and push for the creation of a 20-block historic district in the neighborhood, a portion of which had already been placed on the New York State and National Register of Historic Places in 2000.

Abram thinks a city-designated historic district is crucial to memorializing the immigrant experience properly.

“To tell the story of immigration in this area, one building doesn’t do it,” she said. “This was a whole landscape of people here in these tenements. The home and community life of immigrants was, and is, central to the history of this country. This would be the first historic district in the U.S. to commemorate immigrant history and affordable housing.”

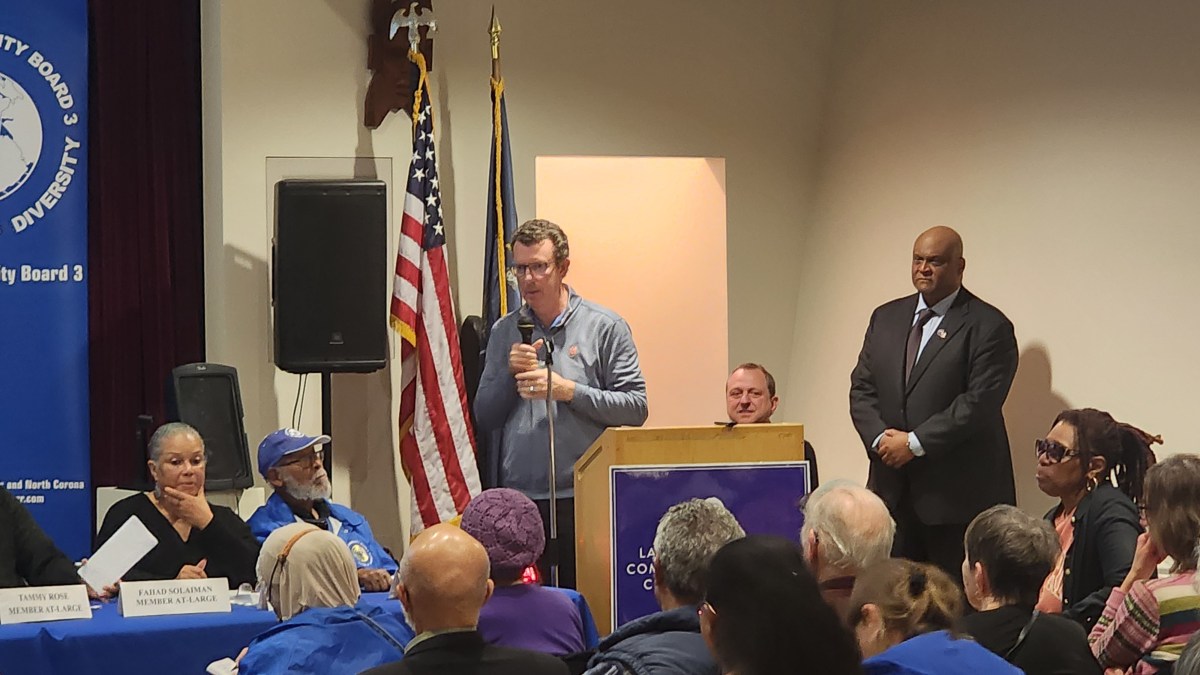

But the coalition, whose proposal met with stiff resistance from property owners at a heated Community Board 3 meeting in March, appears to have its work cut out for it. Sion Misrahi, a prominent Lower East Side property owner and a vocal opponent of the historic district, echoes the sentiment of many when he says, “Pick two or three blocks, but not the whole area.”

He adds that, with landmarking, “changing a window will cost $20,000 and put owners through a lousy bureaucracy,” plus would lead to de facto height restrictions that would result in “short, squat, dark buildings. We should allow for some taller buildings that are narrower and have windows all around,” he said. “They don’t [let you] use an entire lot and [then] allow more space for more light, not to mention balconies.” When an area is designated a historic district, the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, in effect, decides whether a vertical addition to an existing building, for example, is appropriate and how high the addition can be.

Misrahi’s alternate plan would allow for new taller buildings to dot, but not overwhelm, the Lower East Side landscape, achieving a balance, as he sees it, for owners and preservationists alike.

“Every so often, you can have a taller building like the Rivington St. Hotel. They bought the air rights from surrounding buildings, which will stay short forever,” he said, adding, “That’s one way to keep what’s there and still bring new development.”

In August, the coalition submitted an application to Landmarks, which will hold a public hearing if it decides the proposal merits consideration. Either way, Margaret Hughes, director of the Tenement Museum’s immigrant heritage project, emphasizes that the coalition is at the beginning of the process, and has been actively seeking input from property owners and is working hard to address their concerns.

“We’re offering to work with people to develop flexible guidelines on the [preservation] master plan so they can modernize the inside of their buildings and still preserve the historic character of the neighborhood, like Jackson Heights did,” said Hughes. “And we want to figure out a way to create an expedited process to get through the bureaucracy.”

Roberto Ragone, executive director of the Lower East Side Business Improvement District, has talked to both Hughes and area property owners and sizes up the proposal debate this way: “My general sense on the proposed historic district is that there’s caution, some confusion and a need for more information,” Ragone said, referring back to the contentious March community board meeting. “The challenge for the coalition is to demonstrate that the proposal has merit, and that they want to do outreach and build ownership and consensus. It seems like they want to, so we just need to wait and see what happens.”

Meanwhile, coalition members are hopeful as they attempt to reassure area residents and building owners.

“This is not about stopping change in what is a dynamic and evolving neighborhood,” said Amy Milford, deputy director of the Eldridge Street Project, a member of the L.E.S. Preservation Coalition. “No one can stop the market, but it’s important to balance this and preserve many of the buildings that speak to the history and people here.”