Yippie, Stonewall leader, club impresario, activist

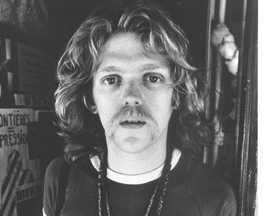

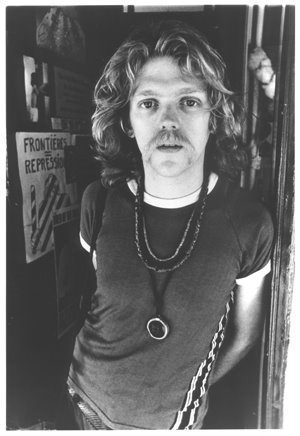

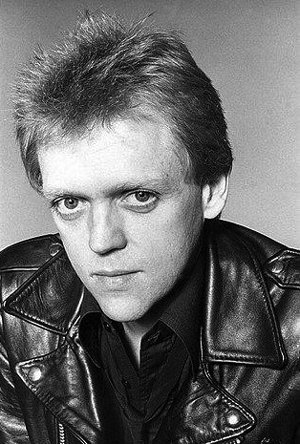

BY LORENZO LIGATO | A history maker: That’s how Jim Fouratt describes himself. The outspoken community activist has been part of the history of Greenwich Village for more than 50 years.

It was 1969 when Fouratt — then a long-haired, slender, aspiring actor from Providence, Rhode Island — took part in the watershed demonstrations at the Stonewall Inn that marked the birth of the lesbian and gay liberation movement.

A self-proclaimed cultural instigator, Fouratt has worn many hats since the old Stonewall days — from gay rights stalwart for the Gay Liberation Front to talent booker at the iconic Downtown nightclub Danceteria, to pop culture critic for Billboard and Rolling Stone magazines.

“I’m a single, gay man. I never wanted to act like a straight person, I never wanted to have children,” the activist said. “But all the gays and lesbians that are out because of what my generation did, they are all my children.”

I reached Fouratt by phone, just a few days before his 71st birthday. The activist was in San Francisco for the Frameline International LGBT Film Festival, the longest-running and largest film exhibition event dedicated to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender programming.

Three documentaries he was featured in would be shown at the festival, Fouratt said.

He talked fast, quite fast. His tone of voice was gentle yet confident and straightforward, while recalling the events that unfolded the night of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia-run dance bar on Christopher St. off of Sheridan Square.

“People that think we are past homophobia and intolerance need to get their heads out of places like the Village, L.A. and San Francisco,” Fouratt said. “But what happened in 1969 definitely changed how lesbians and gays see themselves.”

At the time, Fouratt was a 24-year-old hippie who worked as an assistant to Clive Davis at Columbia Records.

He grew up in the Providence suburb of Riverside, and had moved to the Village at age 15 to work his way into New York City’s avant-garde theater and music scene.

“It was a time where almost everyone in theater was gay or lesbian,” Fouratt noted. “But to the world outside none of us were gay or lesbian.”

Many actors and directors hid their sexuality, since, as well as prejudice, the legal system at the time was stacked against them.

“But some of us could never pass for straight,” the gay activist added. “I guess we were too pretty.”

In those days, he divided his time between the glittering world of Broadway and the Bohemian hubs of the Village artists, like the storied coffeehouse Caffe Cino. Yet, it was only in 1965 that Fouratt took up political activism, after being arrested in Times Square at America’s first Anti-Vietnam War demonstration.

Soon after, he co-founded the Youth International Party — better known as the Yippies, a youth-oriented countercultural movement — along with Abbie Hoffman and Paul Krasner.

The group became known for its farcical and highly theatrical actions, such as nominating a boar called “Pigasus the Immortal” for U.S. president in the 1968 race.

Fouratt prides himself on being the man who thought of sprinkling dollar bills onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in August 1967 as an antiwar protest.

On the night of the Stonewall riot, the gay activist had worked until midnight at his office at Columbia Records. After a nightcap at Max’s Kansas City, the popular nightclub on Park Ave. South, Fouratt was heading back to his apartment in the Village, when he noticed a cluster of police and onlookers in front of the Stonewall Inn.

“Police raids at gay bars were frequent,” Fouratt said. “But something was in the air that night.”

Suddenly, he recalled, the door of the bar opened and a police officer came out, dragging a very masculine-looking woman dressed in men’s clothing — “what we call a passing woman,” Fouratt noted. The woman, handcuffed, was put into the police van, but she somehow got out the other side and began to rock the vehicle.

“That was the moment — the moment when gays and lesbians became conscious that they had power,” Fouratt said.

“There’s a lot people say about Stonewall, but a lot of it isn’t true,” he noted. “What is true and relevant is the transformation of a silent, closeted, invisible community through the sense of self-empowerment and visibility.”

An uproar followed outside the bar and, while the cops requested reinforcement, a swelling group of people gathered outside of the bar. Soon, flocks of gays and lesbians were marching all over Greenwich Village, chanting “Come out!” and calling for change.

That was the beginning of the six-day uprising that went down in history as the Stonewall Riots.

“Yet, Stonewall was not a riot,” Fouratt pointed out. “A riot is when people are out of control and it’s scary. I like the world ‘rebellion’ better: A rebellion is about empowering.”

The slim Yippie activist with the blond mane quickly turned into one of the leaders of the Stonewall revolution. On the third night of the demonstrations, Fouratt helped found the Gay Liberation Front, the first of many lesbian and gay liberation movements that sprouted across the country in the following months.

“There were about 250 people at the first meeting,” the activist recalled. “It was an incredibly diverse group: young, old, white, black, women, all in the same room.”

Once the turmoil of the 1960s came to an end, U.S. politics took a new turn — and so did Fouratt. After a brief sojourn in Los Angeles, the veteran of Stonewall returned to the Village and became an impresario for a series of nightclubs and discos, including Hurrah’s (“the first Uptown disco that became a scene for the younger generation,” he noted), the New Peppermint Lounge (a replica of the popular ’60s dance club that launched the Twist craze) and the legendary Danceteria.

First opened on W. 37th St. by Fouratt and his business partner, Rudolf Pieper, in 1980, Danceteria moved to a three-floor location at 30 W. 21st St. the following year. It became a haven for Downtown dance and rock music artists. Composer Philip Glass, alt-rockers R.E.M. and the then “club kid” and up-and-coming star Madonna were just some of the names that performed at the popular nightspot.

“Danceteria was the last great club where everyone crossed over and came to,” Fouratt said. “I proposed that I would turn it into a successful disco, and I did.”

Even after his nightlife phase came to an end, music and entertainment remained at the center of Fouratt’s life. In the following years, the ex-Yippie became an influential pop culture voice, writing for a series of music and lifestyle magazines, including SPIN, Billboard, Rolling Stone and Attitude. Meanwhile, in his unwavering commitment to political and social activism, Fouratt continued to be involved in progressive politics.

When asked to discuss local and national issues, the Stonewall veteran — who is a member of the Village Independent Democrats club — turns into a real chatterbox. The ex-Danceteria talent booker said he’s a feminist, and was discontented with President Barack Obama’s hesitation to give full support to gay marriage.

“I’m not a single-issue person,” Fouratt noted. “It’s not just about gay and lesbian issues; those are critical matters, but not the only ones I look at when I decide who to support. And when I look at Obama, there are a lot of reasons why I’m disappointed in him.”

An experienced music and film critic, Fouratt never minces his words — especially when it comes to local leaders.

“The kind of politics that is going on in the Democratic Party in New York City disgusts me,” he said.

The activist then proudly admitted that he has voted in every single election since he was legally eligible.

“Even when the only viable choice was to write in my own name,” he added.

Although he rejected the label “politician,” Fouratt took part in the Democratic primary against City Council Speaker Christine Quinn in 2009. He said he raised $20,000 in two weeks, but later withdrew.

When asked about the upcoming City Council Third District election — to succeed Quinn, who faces term limits — he answered that he hasn’t yet decided which candidate he’ll support, but has no plans himself to be on the ballot this time.

Yet, he hoped Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, would run.

“Then you will have three lesbian or gay candidates, and the issues — not their sexuality or gender expression — will be central,” he said. “As the young people say: May the most progressive queer win.”

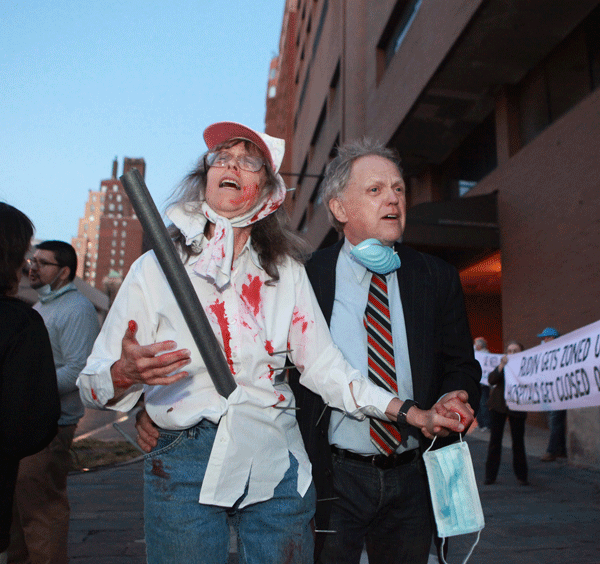

Denouncing the “cheap talk of many politicians,” Fouratt said he’s hoping that leaders will address the local needs of the community. Among the issues he said must be addressed are the planned high-pressure gas pipeline from New Jersey to Gansevoort Peninsula and the restoration of medical services to Greenwich Village in the wake of St. Vincent’s Hospital’s closing.

Fighting to save healthcare in the Village was one of Fouratt’s main planks when he challenged Community Board 2 Chairperson Brad Hoylman for Democratic district leader last year.

The former Yippie also condemned the Village’s ongoing gentrification, responsible, he said, for transforming what used to be a mixed, vibrant community with a diversity of incomes and cultures into a “rich-people-only” territory.

“The Village — and, in general, the whole city — has changed. The artists are gone, many of them died or moved to Brooklyn,” Fouratt said. “That’s very sad for someone like me who remembers the vitality, spark and creativity of the Village’s nightlife and cultural life.”