This is the third story in amNewYork Metro’s five-part series examining the proliferation of grocery delivery services across the city — and the impact they’re having on residents and brick-and-mortar business owners alike. Click to read parts one, two, four, and five.

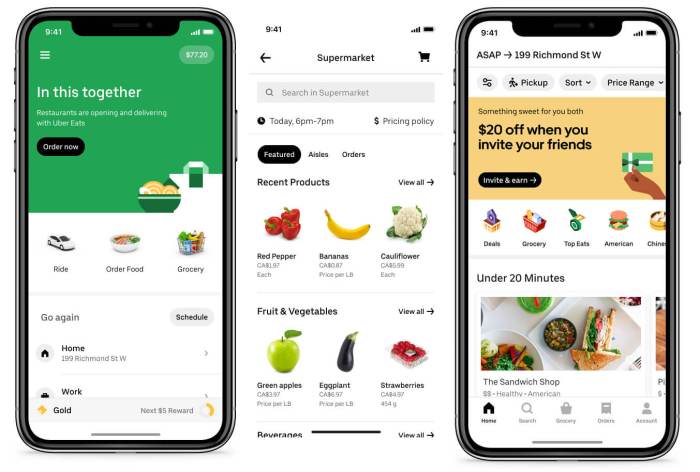

Quick-commerce grocery delivery services like JOKR, Gorillas, and Fridge No More have flooded New York City’s market this year, promising quick delivery and relatively low prices for everything from a full week of groceries to a forgotten dinner ingredient or evening ice cream purchase.

Where traditional grocery stores shell out for big pieces of the city’s pricey real estate to stock thousands of items and keep the store orderly and well-staffed, the apps operate out of “dark stores,” small warehouses carrying about 2,000 items.

The companies say spending less money on rent and dealing with food waste allows them to keep their prices low, about on-par with local grocery stores for most items, and delivery is free or low-cost, unlike more established apps like InstaCart or Fresh Direct.

Grocery stores aren’t the only businesses with something to worry about. For many of the city’s nine million residents, the local corner store is the go-to for a quick purchase. Stocked with the essentials, more than 10,000 bodegas serve their customers faithfully at all hours. In some parts of the city, bodegas are more than a quick stop — they’re the only food store nearby.

While it’s all still new, some grocery store and bodega owners, still recovering from months of lockdowns, are concerned about the disruption.

‘The American Way is done’

“Any bodegas that were in the busy commercial neighborhoods, they didn’t do too well,” said Youseff Mubarez, director of public relations at the Brooklyn-based Yemeni American Merchants Association. “Rents were high, not a lot of foot traffic. But the stores in food deserts, obviously they did their best to stay open and get as much product as they can, but they stayed in business because they were selling what most people in the neighborhood need every day.”

Muhammad Esa, who has been in the retail business for decades, learned the trade from his father and uncles. He has owned Farm Shop Deli on 5th Avenue and 4th Street in Park Slope for twenty years, and said the apps aren’t the first threat to business.

Long before the grocery delivery apps, the business changed when wholesale operators like Costco and BJ’s became open to the public.

“So we are just surviving on necessities that people just need and come and grab,” Esa said. “We’re not really, like, maybe 30 years ago, when we used to be just like a supermarket, we buy wholesale, we buy just like a supermarket. Then things started to change when the wholesale became available to the public.”

Small businesses don’t stand a chance against corporations like Costco or Whole Foods, he feels, because corporations have too much influence over politicians, which has chipped away on regulations that protected small business owners in the past.

“The American Way is done,” Esa said. “It’s just a thing of the past.”

Jose Bello, a Washington Heights native and founder of My Bodega Online, was encouraged by the city’s decision to cap marketing and delivery fees apps like Uber Eats and DoorDash can charge restaurants — but feels it’s unlikely regulations are in the works for new apps.

“This half a billion dollar industry was created in the last 18 months,” he said. “By the time that people realize the effect that they may or may not have —maybe either they burst as a bubble, or they take over everything — it’s too late, they are here.”

Mubarez said more hardship is coming for bodega owners and their employees as emergency grants run dry and the unemployment payments that were allowing customers to spend their money stop.

“Right now, all the businesses are like, ‘I’m making 25, 30 percent less than I was making last month, it’s getting tougher to stay open, and stuff like that,” Mubarez said. “It’s just the worst timing for lower-income communities, they’re getting less money, and then, you know, the more affluent people like landlords are saying, ‘Oh, it’s time to raise rent again, everything is back to normal.’ It’s just widening the gap.”

The potential to adapt

Bello launched My Bodega Online, a delivery platform for bodegas, last year. Many were already delivering informally, he said, when customers would call up wanting something and they’d send out an employee who wasn’t busy on a bike or e-bike.

The app makes ordering and delivering easier and more efficient for bodegas and their customers, and makes the process a little more official for customers who might not be used to calling up to place an order.

Adapting to the new reality and keeping up with technology is critical if bodegas want to stay competitive, Bello said.

“They are so big,” he said of the new delivery services. “Bodegas are not seeing what is coming. Because they’re going to, if not destroy, they’re going to modify the bodegas. Bodegas, if they don’t disappear, they will be kind of the daily sandwich kind of thing, you go to buy lottos, that kind of thing, but the grocery part will not be as strong there.”

Ten years ago, Bello said, taxi services — not just yellow cabs, but private companies who riders would call when they needed a ride — were an integral part of the fabric of New York City, a longtime and iconic part of its streets. But the advent of cheaper ride-hailing apps like Uber and Lyft turned that upside down.

“They had capital, they were the famous people in our parades, they were on every corner of the city,” he said. “And they disappeared. There are a few here and there, they’ve even tried putting out an app, but they kind of disappeared in the influence, in the numbers, and we all use Uber or Lyft.”

“That is coming, it’s upon us.”

Members of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance have been gathering outside City Hall every day since September, protesting what they call a lackluster plan proposed by the city in March to relieve crushing debt accrued when medallion prices soared and made worse when ride-hailing apps changed the fabric of the business. Many of those drivers have been on a hunger strike since Oct. 20.

Needs not met by software

While they’ve expanded quickly, Bello noted that most of the apps are sticking to the same areas within the city – Manhattan, though most don’t broach the island’s northernmost neighborhoods, parts of Queens like Astoria and Long Island City, and Brooklyn neighborhoods like Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn.

“I understand, it’s low-hanging fruit, you want to go where there’s higher income, better users of technology and whatnot,” Bello said.

Mubarez said the bodegas in those areas are the ones most likely to take a blow to business as the apps expand and become more popular — and those stores are also the ones that were already struggling with fewer customers and less revenue during the pandemic.

“When you’re talking about food deserts and low-income neighborhoods, I don’t think these websites accept EBT or food stamps or anything like that,” he said. “Again, it’s not going into the neighborhoods the bodegas are serving.”

A large number of corner stores are immigrant-owned and operated, and they’re a cornerstone for many families, Mubarez said.

“They’re coming here, they’re looking for a job, owners of bodegas are looking for people to hire,” he said. “It’s a simple job, but it pays well, and it comes with enough work to keep you busy. If you’re talking about specific Yemeni immigrants, that’s the only option they have. They barely know the language, they don’t know what to do, and their cousin or their brother has a store, and it’s the first thing they jump into.”

Bello used one of the apps after he stayed overnight in Williamsburg recently, he said, and he was impressed.

“In 14 minutes, I got my product,” he said. “I lost, I lost the game. The only thing that could be different from that experience is that the guy that is coming from the bodega, I know the guy, and that is powerful.”

“The sandwiches, the coffee, the gossip,” he said. “You go to the bodega to know what’s going on on the corner, right, there’s a community component. How do you create a substitution for that? Maybe I’m a romantic, but the bodega is part of the fabric of New York.”

Jay Son, who owns Green Ivy Organic in Gowanus, isn’t too concerned about the grocery delivery apps.

The store, which offers an array of fresh fruits, vegetables, and fresh flowers, is slightly larger than a regular bodega, and is only a block away from the R-train subway stop. Park Slopers headed home from work like to stop in after they get off the train, he said.

Son thinks that the grocery delivery apps don’t carry as many items as his store does. He also believes that customers like to pick out groceries for themselves and enjoy the human interaction.

“People still wanna come and check out the products,” Son said. “And then some people enjoy shopping. This is real life. Those apps aren’t real life. People want to come and talk to the cashier about their day.”

‘The sleeping giant’

Mubarez said bodegas are hardy, but not invulnerable — and he hopes the companies themselves or the city will take action to protect them.

“I’m not going to say we’re not worried, I’m getting a lot of people who are sending me these links, that’s why I’ve heard of JOKR,” Mubarez said. “They have these maps of like, coverage areas that they have, and whenever they come out the deli owner sends them to me, he’s like ‘This is in my area, what should I do?’”

“We have to make sure they’re taking our people into consideration, if they’re not, they’re facing the sleeping giant who is no longer sleeping.”

Next week’s installment of The Race to Deliver series will focus on real estate and transit impacts of the grocery delivery apps.

An earlier version contained the incorrect byline. We regret any confusion which may have resulted.