By Sarah Ferguson

When Lincoln Anderson proposed writing a monthly column for The Villager, I thought, Of course, but how to find time? Ever since the birth of my son, Christopher Zen, I’ve been struggling with how to resume writing and chronicling life on the Lower East Side. My work had been solitary, consuming and barely remunerative. How then to revive my craft amid the chaos of caring for a 2-year-old at a time when writing earns scratch and journalism has been reduced to a nonstop Twitter feed?

“Life Without Compromise,” a new documentary by Suzan Al-Doghachi about three East Village women artists, provided a much-needed kick in the butt.

Shot between 2002 and 2007, the film takes you deep inside the creative process that propels these three women: Australian painter and performance artist Theresa Byrnes, who opened a storefront on E. Fourth St. in 2000 and now has a new gallery called Suffer on E. Ninth St.; sculptor Barbara Monoian, who curated the “Musée de Monoian” in her tiny studio apartment on E. Sixth St., and painter Agni Zotis, who transformed her E. Second St. storefront into a freewheeling salon from 2005 to 2009.

These are women who live art. They make art not against all odds, but because “it is what we do,” as Zotis told me when we gathered at Theresa’s studio apartment, squeezing in among the scores of canvases and paintings tucked into every crevice of the place.

“When people whine, ‘Oh, I have no space to create,’ I want to scream —‘You have a brain!’ ” Byrnes says. “Make video, make anything! If you want to create, you will find space," adds Byrnes, who hosted a jam-packed screening of the film at Suffer earlier this month.

Al-Doghachi says she hopes her portrayal of these women will convey the “spirit and energy” of the East Village. And indeed, it’s significant that all three created salons to interact with the community around them, bravely carrying the torch of East Village bohemia at a time when so many others have fled the coop.

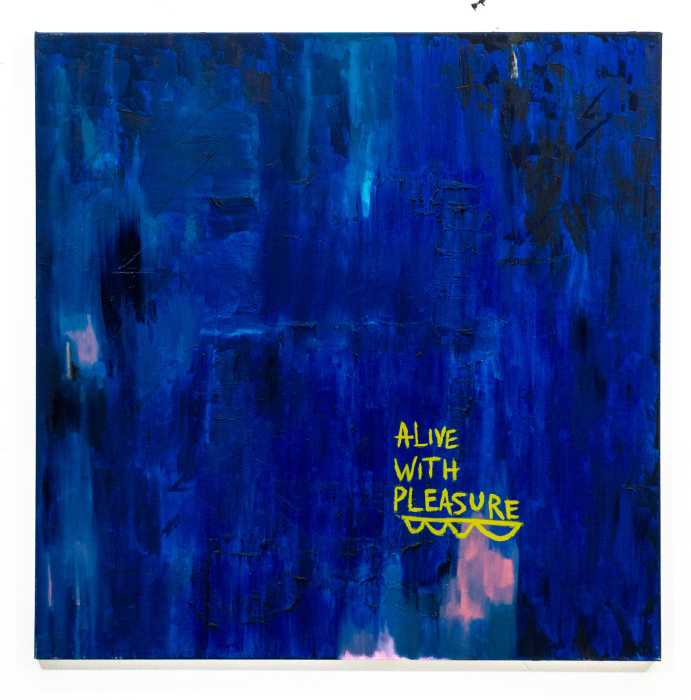

Al-Doghachi, who recently left the East Village for the remote mountains of Belize, says she got inspired to make the documentary after meeting Byrnes in 2002. It’s easy to see why. The film opens with Byrnes talking about how she works in a near “constant state of euphoria,” driven by ideas that “unfold” like scrolls in her mind. As she speaks, the camera pans over a prodigious array of abstract paintings and portraits that fill Byrne’s former studio in Chelsea. Byrnes “suffers” from a degenerative nerve disease called Friedreich’s ataxia that destroys muscle control. I say "suffer" in quotes, because the film underscores her indomitable drive to make art and express herself regardless of any physical limitation.

“Life Without Compromise” captures the intense physicality and vulnerability of Byrnes’s performance art. We see her strung upside down like a gutted carcass in a piece connecting meat-eating with war. Or drizzling ink over her crotch in another “eco-feminist” work about women and war. Later we see the dribble of ink that pooled under her crotch mounted and framed as a delicate ink abstraction. “There are no accidents,” Byrnes says.

Jump-cut to Monoian paddling a canoe with her pit bull mutt in a misty inlet in southeast Alaska. Monoian began working as a commercial fisher in Alaska in 1988 to help pay for college — and then her art. But clearly it is the overwhelming beauty and intensity of this immense natural environment that sustain her.

We see her sinewy hands cracking open king crabs on the deck of her old fishing trawler in Alaska. Then a close-up of these same strong hands rinsing out hog intestines in the sink of her East Village apartment. Monoian stretches and splays the intestines to create unearthly orbs and mummy-like figures. Other sculptures feature deerskin, antlers, bones, rock and tightly bound feathers.

From 2003 to 2007, Monoian transformed her tiny, 260-square-foot apartment into a gallery for her work and then opened the door to others, eventually displaying more than 300 pieces by some 90 artists, most from the East Village. The place was like a curio box full of energy-charged creations, yet amazingly uncluttered.

Somehow she also managed to cram a lot of people into the place. The documentary captures an opening, with scores of folks spilling out into the building’s stairwell and partying in the backyard. “I love living in New York, I can’t even believe the people I’ve met,” Monoian enthuses.

Agni Zotis, who grew up in Queens but spent her youth hanging on the L.E.S., comes off as a more traditional artist, working canvases with feverish intensity. But it is her compulsion to create that fascinates. She describes painting as a spiritual and metaphysical practice — a means of “finding oneself and making peace with that” — or even guiding one’s destiny. “I’m fascinated with the energy of God,” she says in the film, “with energy forms and molecular structure.”

Clearly she tapped into some kind of morphic field when she took over the storefront at 127 E. Second St. — formerly home to Ajax Films, which Al-Doghachi shared with her husband and filmmaking partner, Robert Flanagan. I remember meeting Zotis there around 2006, and feeling amazed that she could sustain such a place in this era of soul-crushing rents. The studio was light and airy and filled with colorful paintings and Hindu and Buddhist icons. Zotis was incessantly creating. But she left her doors open to passersby — hosting openings and performances that brought together accomplished artists alongside folks like Dusty, a homeless jazz saxophonist who used to busk outside the Second Avenue subway.

“Life Without Compromise” captures that raw energy. There’s one ecstatic scene when Zotis stages a live-action painting accompanied by bassist Christian McBride and poet Gary Glazner. “I’m having so much fun!” she screams, swooning before the crowd in an off-the-shoulder gown splattered in paint. You have to relish her triumph.

But like all East Village stories, this cannot last. At the end of the film, Zotis bids farewell to her East Village salon — her “lover” she calls it — riding off into the sunset on a pink cruiser bicycle. “My lease was up and I realized if I kept the space, it would take so much energy to sustain that I wouldn’t see my son grow up,” Zotis told me. “My gallery needed so much energy to be. It was like a magic box. To manifest it needed a lot of intention. I was producing a tremendous amount of work. But it took all my sweat and blood. I don’t feel that young anymore. At this point I want the art to actually pay for it,” adds Zotis, who is now painting and making video works from her apartment in Chelsea.

Similarly, by 2008 Monoian had lost her rent-stabilized lease and decamped for Pittsburgh, where her sister had purchased a Victorian row house along the Allegheny River. She’s currently creating a new “musée” of East Village artists in exile — adding new works to her collection, like pieces of Eddie Boros’s former tower in the Sixth Street Community Garden, which she managed to collect just as the Parks Department was tearing it down.

“I needed space, real space, and now I have it,” Monoian says. Yet she makes frequent trips back to the East Village to “refuel” her psyche. “I still miss the pulse of the city,” she says.

Byrnes, on the other hand, has expanded her East Village presence since the film was made. Last winter she left her Chelsea studio to open Suffer, just up the street from her storefront apartment on E. Ninth St.

“I felt like I needed to come home,” Byrnes explains. “In Chelsea, I had more space and light, so I could go big and my work became lighter. But I missed waking up and rolling out of bed and into my work. In a way, I had to leave the East Village to grow and to realize my work — and to realize I wasn’t missing anything.”

“Life Without Compromise” will be screened again on Sat., March 26, at 7 p.m. at Suffer (616 E. Ninth St.) — where works by all three women will be on view through Sun., April 3.