The collection of music publishers and songwriters responsible for vast contributions to the “great American songbook” just became part of the great New York cityscape.

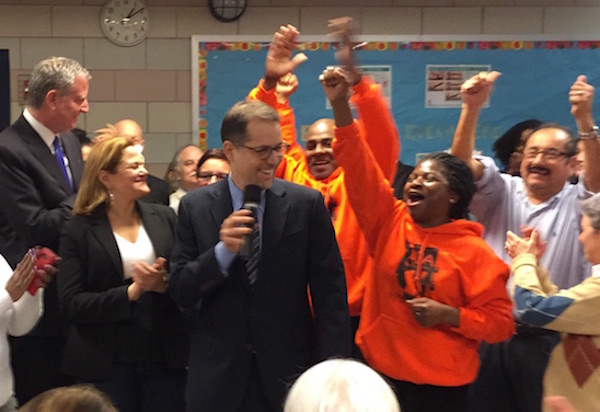

Preservationists, historians and Manhattan officials came together on Saturday to unveil the official Tin Pan Alley street sign at West 28th Street and Broadway commemorating the area of New York that became known as the birthplace of American popular music.

“This is the first place where artists could make a living by writing songs, which we take for granted now. That started here,” said Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine.

The area known as Tin Pan Alley was a locus of various sheet music publishers, composers, and performers who worked together in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to create what is now known as the beginning of American pop music. The area’s nickname was originally a derogatory reference to the racket made by the chorus of pianos playing different tunes, akin to the banging of pans in an alley. Its hits, some still common today, include “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “God Bless America.”

The new “co-naming” status of the historical district follows the designation of 47-55 West 28th Street as an official city landmark from 2019, which formalized the group of buildings into a Tin Pan Alley Historic District.

“The co-naming is a major milestone because now everyone in perpetuity who walks by … will see that it’s Tin Pan Alley and will know where it is. Tin Pan Alley is a global phenomenon. Not everyone knows that it was in one specific place,” said George Calderaro, director of the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project.

The musical styles of Tin Pan Alley range from waltzes and marches in its early days to the rise of ragtime.

NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission researcher Kate Lemos McHale talked about how the rise of Tin Pan Alley provided significant milestones for populations of Eastern European Jewish immigrants and the shift of many in America’s black population to New York beginning in the early 1880s.

“It brought ragtime to an international public, offered unprecedented opportunities for black artists and publishers to create mainstream American music,” Lemos McHale said.

She did not neglect to mention, however, that learning the history of the area also means acknowledging the existence of racist minstrel songs that were published by some prominent Tin Pan Alley songwriters in the reconstruction era of the industry.

John Reddick, a black historian who spoke at the event, added that the legacy of the music district also included new opportunities to Black performers and songwriters.

“It was the first time African Americans didn’t come to the street and just get paid for the song and become anonymous,” Reddick said.

In addition to remarks on the historical legacy of Tin Pan Alley, the event featured singing performances from the Jesse Breheney Trio with a vocal performance from Liora Michelle.

The effort to preserve the history of the musical district comes as a result of advocacy from the culture and historical organization the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project. In his remarks, Councilman Eric Bottcher, thanked its director, Calderaro, who was behind the push for the co-naming as well as the historical landmarking.

“Because of George’s efforts and the efforts of so many of you, Tin Pan Alley is gonna be here for generations to come,” Bottcher said.