Retired subway signal maintainer Frank Tarulli is still processing his traumatic experiences of 9/11, when he rushed to the World Trade Center site after the Twin Towers collapsed and found the hellish scene covered in dark ash and a burnt smell.

“It looked like nighttime, it was so clouded and just looked so dismal down there,” said Tarulli. “It was almost like breathing in something solid, that’s how bad it was.”

The retiree was part of a convoy of hundreds of transit workers delivering safety equipment and heavy machinery to Ground Zero after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks.

Along with police and firefighters, employees from across the mass transit system were at the forefront of the 9/11 rescue efforts, transporting New Yorkers fleeing from Lower Manhattan to their homes and repurposing their heavy equipment and detailed knowledge of the city’s infrastructure to recover survivors from the rubble.

“Every time there’s a disaster, all city workers become emergency workers, and that’s what we were,” said Tarulli. “The cops and the firemen were the frontline, we understand that, but we were right there with them.”

System shutdown

Metropolitan Transportation Authority managers at the Subway Command Center (the subway’s nerve center in Midtown now called the Rail Control Center) decided to shut down subway service at 10:20 a.m., after the collapse of the South Tower and eight minutes before the fall of the North Tower.

The collapse crushed the Cortlandt Street station underneath the World Trade Center on the 1 line, with steel beams piercing through 7 feet of earth, through the brick and concrete ceiling, and onto the track bed.

“There were beams that pierced the tunnel like a needle through cloth,” said Kevin McCawley, a former transit communications technician who worked to set up communications in the days following the attacks.

“It was kind of creepy as you’re going along the subway tunnel, everything looked normal and then the wall looked a little caved in at the top and — boom — you just hit a wall of debris,” he said.

As people fled Manhattan and with the subways down, MTA rerouted its buses to pick people up and shuttle them to safety.

One of those drivers was Ron Gibson, who remembers throngs of dust-covered New Yorkers streaming toward him on the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge.

“They were coming, like thousands,” he said. “I tried to carry as much as I can, I didn’t care if they were on the roof.”

Confusion and comfort

For the MTA, it was much harder to communicate to riders quickly, unlike now when anyone can just look up train service immediately on their phones, said Rob Del Bagno, manager of exhibitions at the New York Transit Museum.

“It was terrifying to not know what was going on and to not know what you were supposed to do,” said Del Bagno. “You’re changing things minute-by-minute and yet you’ve got to be able to communicate that.”

The transit historian curated an extensive exhibit in 2015 at the Downtown Brooklyn museum about the transit agency’s response and recovery from crises including 9/11, the 2003 Blackout, extreme weather events, and Superstorm Sandy, called Bring Back The City, which is still available to view online.

He was one of thousands who walked from Manhattan over the Williamsburg Bridge and he remembered how, despite the chaos and uncertainty, the steady presence of public transit was a welcome relief to him and fellow New Yorkers when he got on a bus in the north Brooklyn neighborhood.

“They asked me where I was going and they told me what bus to get on. I ended up getting on a bus and getting a ride home, somebody handed me a bottle of water,” he said. “It was a very disturbing time but having the transportation systems being there for you was a comforting thing.”

In addition to the buses, ferries and other boats and ships set sail en masse to collect people from Manhattan’s piers and seawalls, as has been detailed in the 2011 short documentary “Boatlift.”

Within hours of the attacks, the first trains were back up, but bypassing Lower Manhattan. By the end of the day, almost two-thirds of the system was operating and, miraculously, no lives were lost on the subways that day, according to the Transit Museum exhibit.

Clearing the debris

In the days and weeks that followed, MTA transported first responders to and from Ground Zero and provided their heavy machinery previously used for moving subway tracks to help clear steel beams and other large debris.

“Transit were the first people on the scene with their structural equipment,” said former bus driver Gibson, who volunteered to bring cops and firefighters to Ground Zero for a year afterward. “They were the ones that had the equipment to move steel beams.”

Some workers joined the so-called Bucket Brigades, lifting smaller objects out by bucket and by hand to make way for emergency personnel looking for survivors.

“It was eerily quiet, except for the heavy machinery,” recalled Ray Miranda a retired lights maintainer. “I noticed there were no pigeons, no birds. It looked like a ghost town, like a nuclear bomb had gone off.”

The transit electrician helped install emergency generators to power the area’s traffic signals, lighting and computers, since much of the power and cell connectivity had gone down.

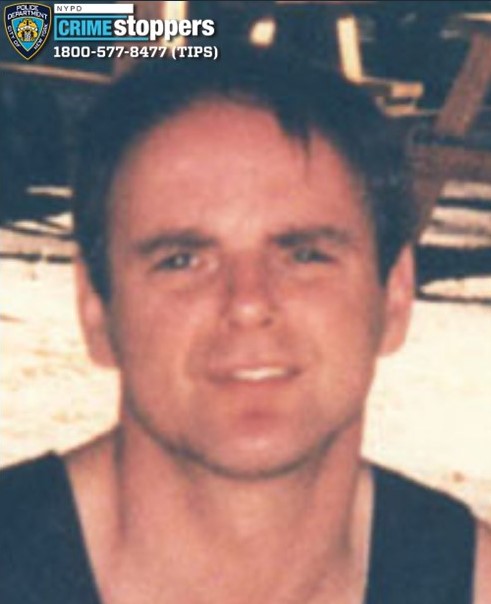

McCawley, the former communications technician, would put in 16-hour shifts clearing detritus until his arms tired out, joined by his late friend and co-worker Pete Foley, who passed away from a 9/11-related illness in 2012.

“We would shoot up to his place in the Bronx and sleep, put on the same clothes, and head back down,” McCawley said. “We didn’t change our clothes. If you were down there within a half an hour, you’d be covered with grey dust anyway.”

Back on track

Transit employees worked around the clock in the coming months to bring back service to the downtown 1 line, which resumed operations there by mid-September 2002.

The Cortlandt Street Station didn’t open until 17 years later, in 2018, rechristened WTC Cortlandt with an entrance to the Oculus Transportation Hub as part of the reconstructed World Trade Center campus.

As the 20th anniversary of that awful day approaches — and many first responders still suffer, or have died from, illnesses relating to the toxic ash-filled air at the World Trade Center — transit heroes like Miranda can’t help but relive the tragedy in their minds around September, while at the same time finding hope in the camaraderie of everyday New Yorkers they were a part of.

“I still pray for my co-workers and I hope their health continues to get better, I hope they find some solace and gratitude in the work that we did down there,” Miranda said. “The impact of 9/11 where everybody was just pulling for one another. It made me feel like the city was moving back, the service that we did.”