BY ALBERT AMATEAU | The 105th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire drew a crowd of 400 on Wed., March 23, including relatives of victims who perished in the tragedy, labor union members, firefighters and neighbors.

They gathered at the intersection of Washington Place and Greene St., where a Fire Department company in front of New York University’s Brown Building raised its ladder to the eighth floor.

It was the highest that ladders could go on that tragic Saturday afternoon, March 25, 1911, when a fire that started in a waste bin engulfed the eighth, ninth and tenth floors of the then-Asch Building, now the property of N.Y.U.

Most of the 146 employees who died, ranging in age from 14 to 42 and most of them young women, worked on the ninth floor.

As each victim was named at the commemoration last week, a white carnation was laid on the sidewalk. Then red carnations were laid in honor of people who died over the years in garment factory fires in North Carolina, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Russia and elsewhere.

Among the neighbors at the event, members of the Washington Place Block Association distributed handbills denouncing a proposal by Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition to erect a memorial to the victims.

The proposal, for which Governor Cuomo has pledged $1.5 million, calls for three sets of reflective steel panels. There would be two horizontal panels, one at hip height and the other above head level, encircling the two street sides of the building. Names of the victims inscribed on the top panel would be reflected down to the bottom where they could be read by passersby. Another metal panel would run up the building’s southeast corner from the ground to the eighth floor.

Howard Negrin, president of the block association, said, “The proposal is garish and gimmicky. It belongs more on Times Square. It lacks dignity and dishonors the memory of the tragedy’s victims.”

Negrin also said the reflective panels would shine into the windows of residents across the street.

At a Community Board 2 town hall meeting in February, Joel Sosinsky, a spokesperson for Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, said the project would be illuminated by sunlight and LED lights at the top to enable reflections to reach down to the ground. The display would be visible from “several blocks away,” according to coalition statements at the meeting.

The coalition still has to raise about $1 million for maintenance and insurance for the project. Since the Brown Building is a designated city landmark, as well as a National Historic Site, the final plan must go to the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission for review.

Terri Cude, C.B. 2 first vice chairperson, said last week that the board would review the plan after it is submitted to L.P.C., probably by the end of the year.

Absent from the commemoration for the first time in the past several years was Michael Hirsch, an East Village resident and a recognized authority on the history of the Triangle Fire. He, too, is opposed to the proposed memorial.

“All you have to do is stand on the cobblestones of Greene St. at Washington Place and see a streetscape virtually unchanged from 1911,” he told The Villager last week. “There’s nothing like it in the city. History was played out there.

“Just around the corner was where the Stonecutters’ Riot broke out around 1834,” Hirsch said. “The stonecutters were protesting the use of prison labor to quarry and dress stone for public and private buildings.

“There’s no way that an eight-story-tall series of mirrors could do anything but deface this building. There should be something that supplements the plaque that’s already there.”

Hirsch, a professional genealogist and writer, began working on the history of the Triangle Fire several years ago, inspired by a 2003 book by David Von Drehle, “Triangle: The Fire That Changed America.”

Hirsch undertook the task of untangling the names of the fire victims and finding the identities of six previously unknown victims.

“It took four years to straighten it all out,” he said.

Hirsch tries to visit the graves of all 146 victims of the fire at least two times a year.

“It’s a mitzvah [Hebrew for a charitable act commanded in the Bible] for me, and I’m in touch with 90 percent of the victims’ relatives,” he said.

That means lots of visits to cemeteries, 16 of them, according to Hirsch.

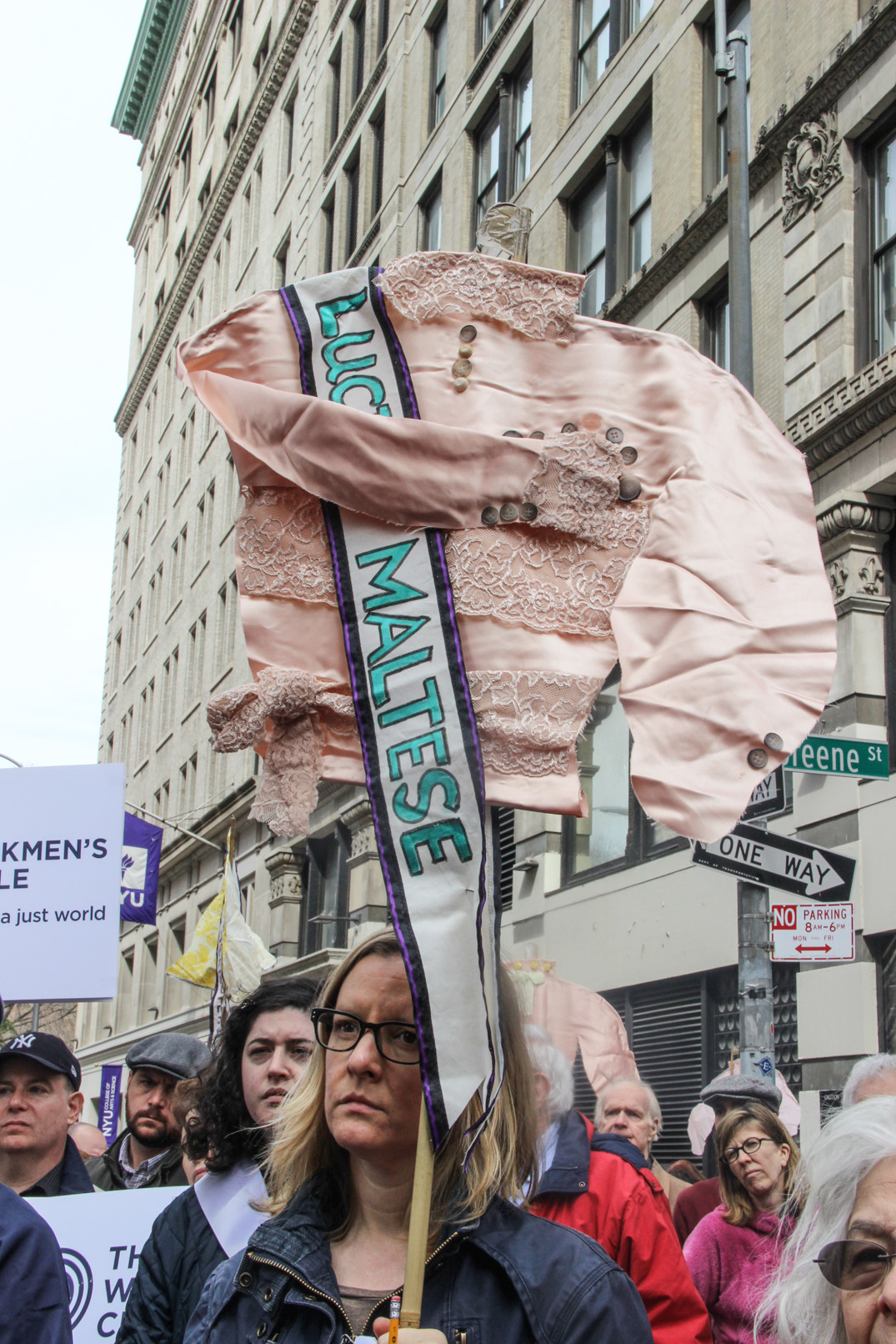

Some families lost more than one to the fire. Hirsch cited the Maltese family, which lost three members. The eldest, Caterina, was 30. Rosaria and Lucia were her younger sisters; all are buried in Calvary Cemetery in Maspeth, Queens.

The Weiner family lost Rosie, 19, but her sister Katie, 16, who also worked at Triangle, survived the fire. March 25 was a fateful date for the Weiners; eight years earlier, another sister, Esther Weiner, was killed in a March 25, 1903, streetcar accident in Lower Manhattan.

Sarah Brenman and her sister Rose, in the country only a few weeks, both perished in the fire.

“I found one victim, Lizzie Adler, who lived on my block on E. Sixth St.,” Hirsch said.

Rosa Grasso, 14, one of the three youngest victims, was buried in Calvary Cemetery without a headstone.

“I put an entry on my Facebook page a few years ago, saying I wished I could get a headstone for Rosa,” Hirsch recalled. “And Rachel Grant Meyer, one of the rabbis at Rodeph Sholom on W. 83rd St., saw the entry and convinced the synagogue to donate a headstone for her.”

The owners of Triangle Shirtwaist, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, were tried for manslaughter before Judge Thomas C.T. Crain. The all-male jury acquitted them. While the conventional wisdom holds the acquittal to have been a travesty of justice, Hirsch believes the jury was justified.

“The assertion that the doors on the ninth floor were locked was not based on reliable testimony,” Hirsch said. “The defense attorney, Max Steuer, did not have a hard job dealing with it,” he added.

Survivors who said the doors were locked appeared to be testifying according to a prepared script. There was testimony that when a ninth-floor door finally opened and before the eighth floor took fire, victims feared the smoke and ran up to the 10th floor. Panic prevailed and several people jumped to their deaths.

“The owners were in the building at the time, and two of the victims who died, Jacob Bernstein and Max Florin, were related to Blanck,” Hirsch said. “Esther Harris, said to be Isaac Harris’s favorite niece, was horribly injured in a fall down an elevator shaft. Although she survived and recovered, she died young.”