BY ALINE REYNOLDS | If someone were to see a person collapse on the sidewalk, it’s best not to check the victim’s pulse or apply mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Using hands-only chest compressions and or an automated external defibrillator are the most effective means of stabilizing a patient while an ambulance rushes to the scene.

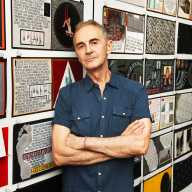

That’s what city Emergency Medical Service officials told a dozen Downtown residents and workers last Monday during a training session organized by the Tribeca Community Emergency Response Team (C.E.R.T.). The group was taught the basics of how to revive those who are suddenly thrown into cardiac or respiratory arrest, simply by pushing down approximately two inches onto their chest using the palms of one’s hands.

Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation can double or triple a person’s chance of surviving cardiac arrest, according to the American Heart Association, but recent studies show that less than one-third of victims receive it.

While the survival rate among cardiac arrest victims who receive chest compressions parallels that of those who receive mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, hands-only CPR has the advantage of being easier to remember and execute than is mouth-to-mouth breathing, according to the American Heart Association.

“I think people really are reluctant to touch people on the mouth, which has been a key component of the Red Cross training that we had taken,” said Jean Grillo, head of the Tribeca C.E.R.T. team. “When it was finally determined you can keep a heart beating through compression only, at least long enough to get the E.M.S. help there, it was really worth trying.”

At last Monday’s drill, Mike Koenke from the F.D.N.Y.’s CPR training unit instructed those present to confirm that the victim is unresponsive, call 9-1-1, and then perform two minutes of chest compressions, averaging at least 100 compressions per minute.

“Feel the burn!” Koenke exclaimed as the C.E.R.T. members rhythmically pumped mannequins’ chests to the beat of a techno song playing in the background.

Koenke added, “You’re looking for obvious signs of life, like normal breathing, eyes opening, or moaning.”

In the event of an actual emergency, Koenke advised the C.E.R.T. members to continue with the compressions even if they hear popping underneath the patients’ chests, signaling ribs fractured by the pounding.

“Broken ribs heal, but stopping compressions can ensure death,” according to a training video Koenke showed the group to reinforce the steps of the life-saving technique.

Next, the C.E.R.T. team learned how to use a defibrillator, which is equipped with a computer chip that detects ventricular fibrillation, a severe form of cardiac arrhythmia. A.E.D.s are found in many public facilities including schools, airports and arenas, and they will soon be installed in subway stations, according to Koenke. C.E.R.T. team members are distributing maps around the neighborhood that identify Downtown facilities that have the machine.

When used properly, the machine stops the heart and corrects its rhythm nearly instantaneously, similar to the way a computer reboots itself, Koenke said.

Koenke cautioned the group that those using the A.E.R. should not make contact with the victim’s body and should keep bystanders at a distance in order to avoid getting an electrical shock.

Those who participated in the drill, including Hudson Square resident Tricia Nash, found the C.P.R. training useful and are grateful to know how to rescue someone who is at death’s door.

Nash, a C.E.R.T. member for four years, said the session was a helpful refresher of skills she had acquired in a previous drill.

“It’s good just to be reminded, because it’s not something you practice,” said Nash.