[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

- A portrait of Gen. Horatio Gates painted by Gilbert Stuart around 1793-1794 hangs in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Stuart painted Gates long after the Battle of Saratoga, which took place in 1777 and which the American forces won under his leadership.

BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new galleries of American painting and sculpture, which debuted on Jan. 16, Downtown residents can come face to face with some of the people who once walked Lower Manhattan’s streets.

George Washington emerged from the American Revolution as a totemic figure, but his preeminence was not always assured. Gallery 753 holds three portraits of Washington and one of his subordinate and adversary, Horatio Gates.

Both men, at one point in their lives, lived in Lower Manhattan. Washington came here at the end of the war, was inaugurated here as the first U.S. president in April 1789 and served the first months of his presidency here until the capital moved to Philadelphia. Gates lived in New York City at the end of his life and is buried in Trinity churchyard at Broadway and Wall Street, in an unmarked grave. Horatio Street in Greenwich Village is named for him.

In the early years of the war, Washington was disastrously defeated at the Battle of Brooklyn and was again trounced in and around Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Gates with the help of the brilliant general Benedict Arnold, who ultimately betrayed the Colonial cause, defeated the British in upstate New York at the Battle of Saratoga in September and October of 1777. Some people wanted to demote Washington and put Gates at the head of the Continental armies. That didn’t happen, of course, and Gates may or may not have been an active participant in that plan. No one knows.

The portraits of Gates and Washington in the Met are probably good likenesses. The same cannot be said of a statue of the 21-year-old Connecticut schoolmaster Nathan Hale, who undertook the dangerous mission of entering British-held New York City in September 1776, trying to gain information for George Washington. Hale was caught and hanged as a spy. His last words were, “I regret that I have but one life to give for my country.”

In 1893, the Sons of the American Revolution in the State of New York erected a statue of Hale in City Hall Park. A miniature version of the work by sculptor Frederick MacMonnies is in the Met. MacMonnies had no idea what Hale looked like. He depicted him as a handsome, young man — his eyes closed as a shield against his impending fate.

Aside from these specific references, the American galleries at the Met display furniture, silver, glassware, china and even complete rooms from the era before, during and after the Revolutionary War. Under construction, the streets of Lower Manhattan often yield fragments from that era. The Met galleries show gleaming and whole what otherwise could only be pieced together or imagined.

The American wing of the Met is a permanent installation, but the exhibit of drawings, “Rembrandt’s World,” which opened at the Morgan Library & Museum on Jan. 20 will only be there until April 29. Four remarkable Rembrandt drawings are in the exhibit. The rest are by his contemporaries.

Rembrandt van Rijn was born in 1606, three years before Henry Hudson, sailing for the Netherlands, entered what is now New York harbor. The Dutch relinquished control of Nieuw Amsterdam to the English in 1664 — five years before Rembrandt died. So the span of the great artist’s life — and the years covered by this exhibit, roughly coincided with the founding of what is now New York City and its growth under Dutch rule.

“Rembrandt’s World” shows what the colonizers of Nieuw Amsterdam left behind — the buildings, the markets, the frozen canals in winter where they skated, the ships they used to fight the Spanish and the English, and to explore the world. It shows windmills, churches, bridges and ordinary homes. It shows how people dressed and what they celebrated. It even shows what they looked like.

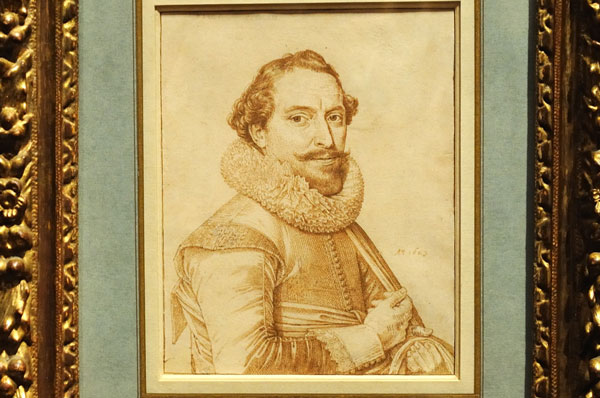

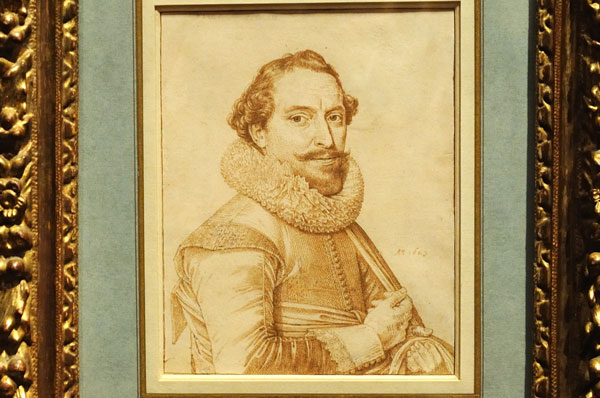

One portrait in the exhibit is of a merchant and politician named Cornelis Bicker (1592-1654) by an artist named David Bailly, who also depicted Bicker’s wife, Aertgen Witsen. The description reads, “They both descended from old patrician families in Amsterdam, where their fathers were successful grain merchants and mayors. Cornelis and his three brothers came to dominate world trade, controlling goods coming in and out of the Netherlands from the Americas, East Asia, and the Mediterranean.”

So this well-dressed man with intense, dark eyes, only in his early thirties but already with a crease in his brow, would have been among the wealthy investors in the Dutch West India Company that financed Nieuw Amsterdam and who profited from the riches that this and other colonies returned to the mother country. This wealth, in turn, financed the artists whose drawings of contemporary life were eagerly collected by the newly affluent Dutch burghers.

For more information about visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is on Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street, go to www.metmuseum.org

For more information about the Morgan Library & Museum, and the special programming of lectures and films associated with the exhibit, “Rembrandt’s World,” go to www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/exhibition.asp?id=58. The Morgan is at 225 Madison Ave.