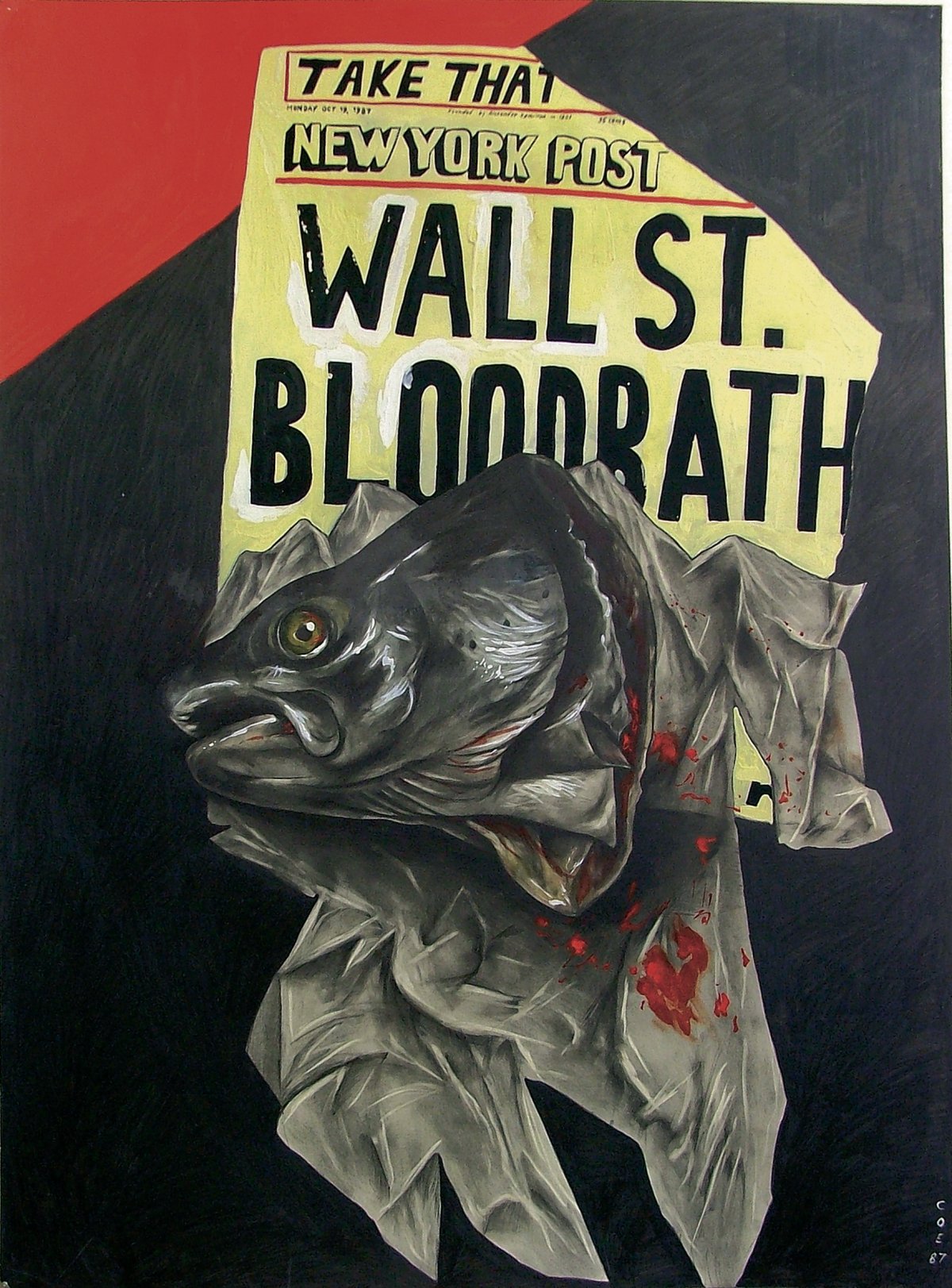

BY ALAN KAUFMAN | Last Gasp, legendary San Francisco publishers of underground comics and art, have just released my latest book, “The Outlaw Bible of American Art,” an anthology spanning more than half a century of underground visual culture.

Fourth in my “Outlaw” anthology series, which includes volumes on poetry, literature and essays, the “Outlaw Bible of American Art” contains a generous and even disproportionate number of visual artists from the Lower East Side, the East Village and the West Village, proving once more that the Village has been and continues to be the epicenter of underground art in America.

But just as significantly, the book offers a radical new take on the history of American art. It is an alternative canon — a roll call of often overlooked and forgotten creators — and an antidote to the soulless vacuousness of Andy Warhol, the vapid commercialism of a John Currin.

It is, too, a course correction to the corporate commodification and self-betrayals of the co-opted underground itself, in which, say, a skateboarding wheatpaster like Shepard Fairey willingly courts his own commercial appropriation in order to become a designer brand.

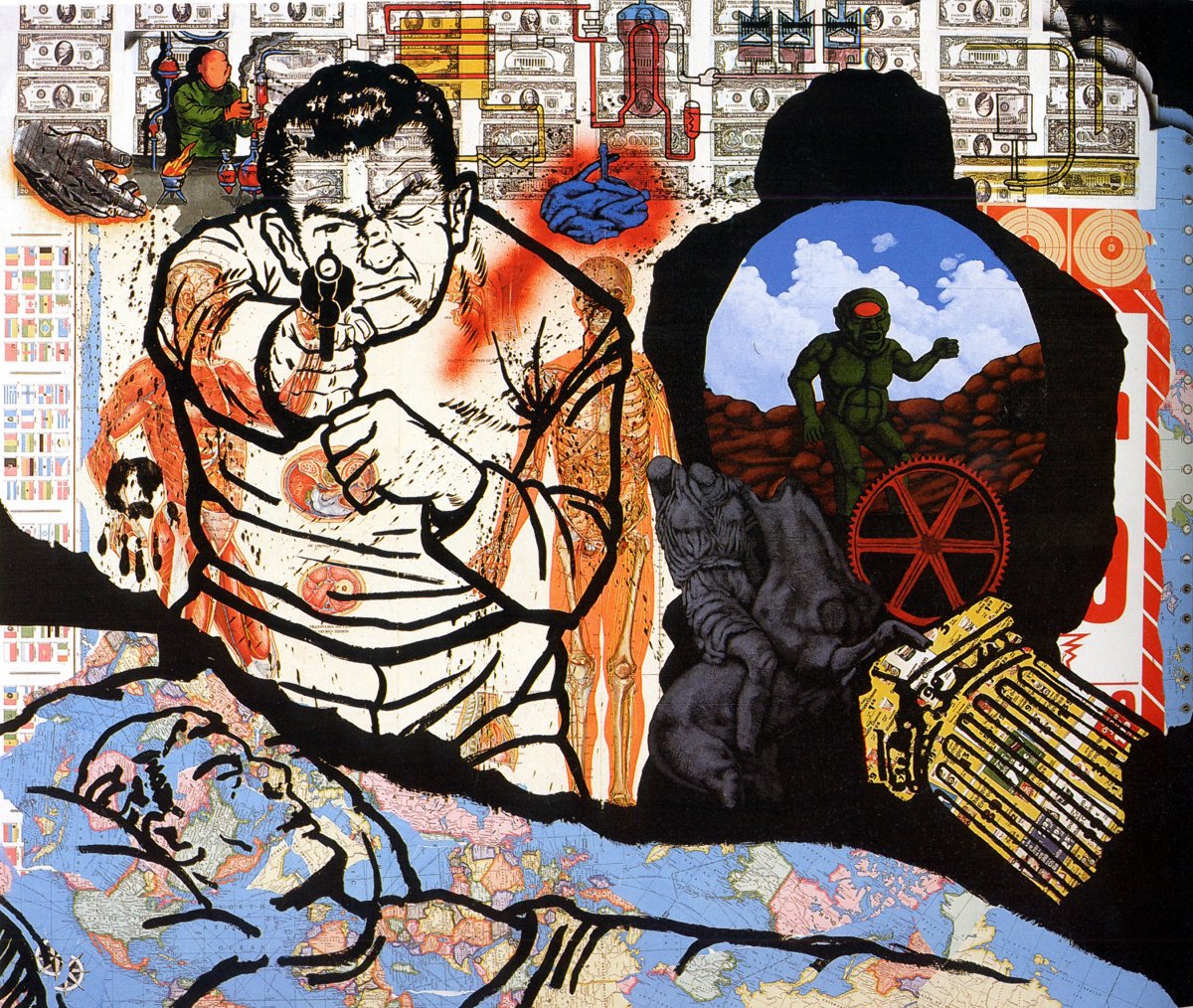

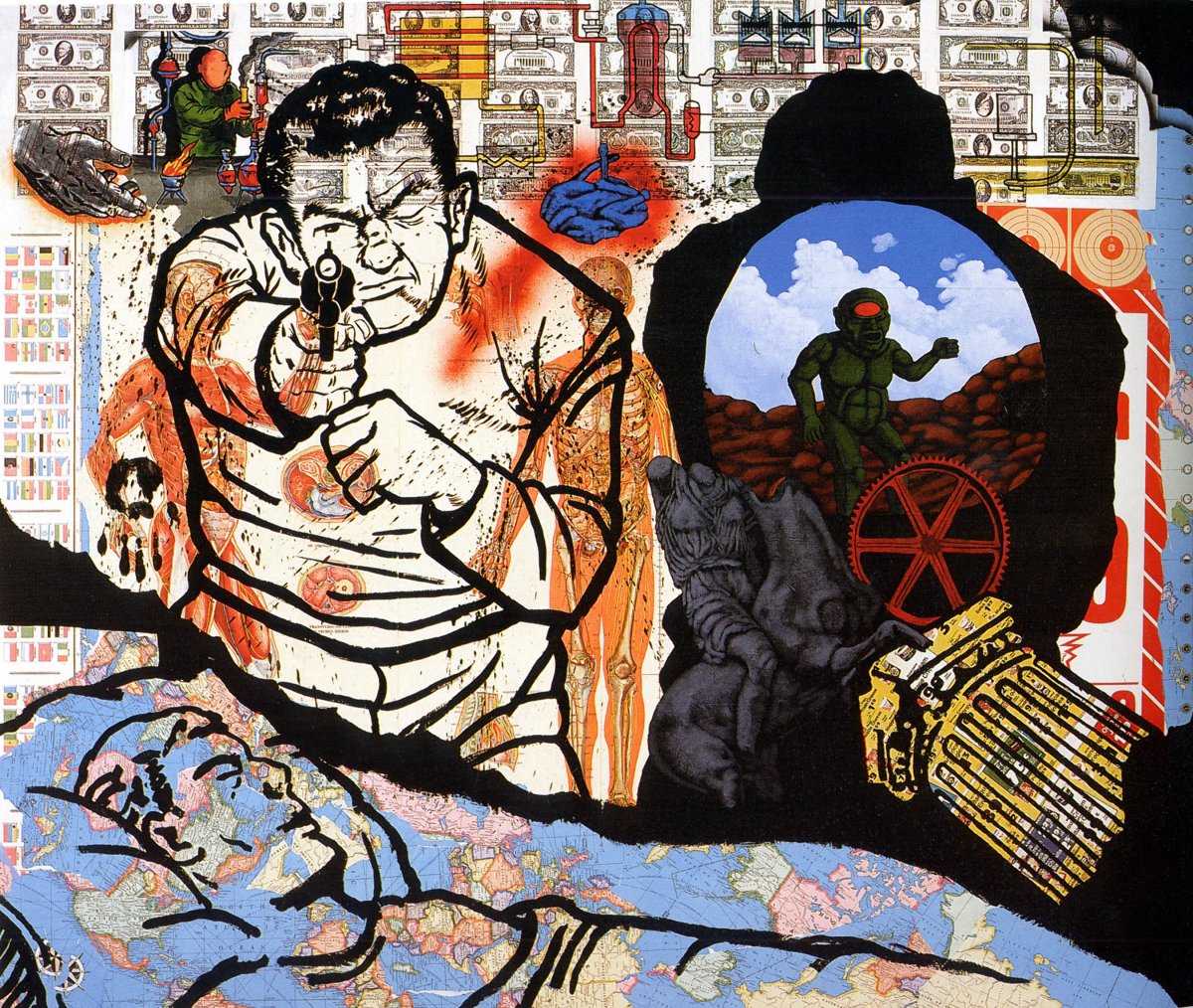

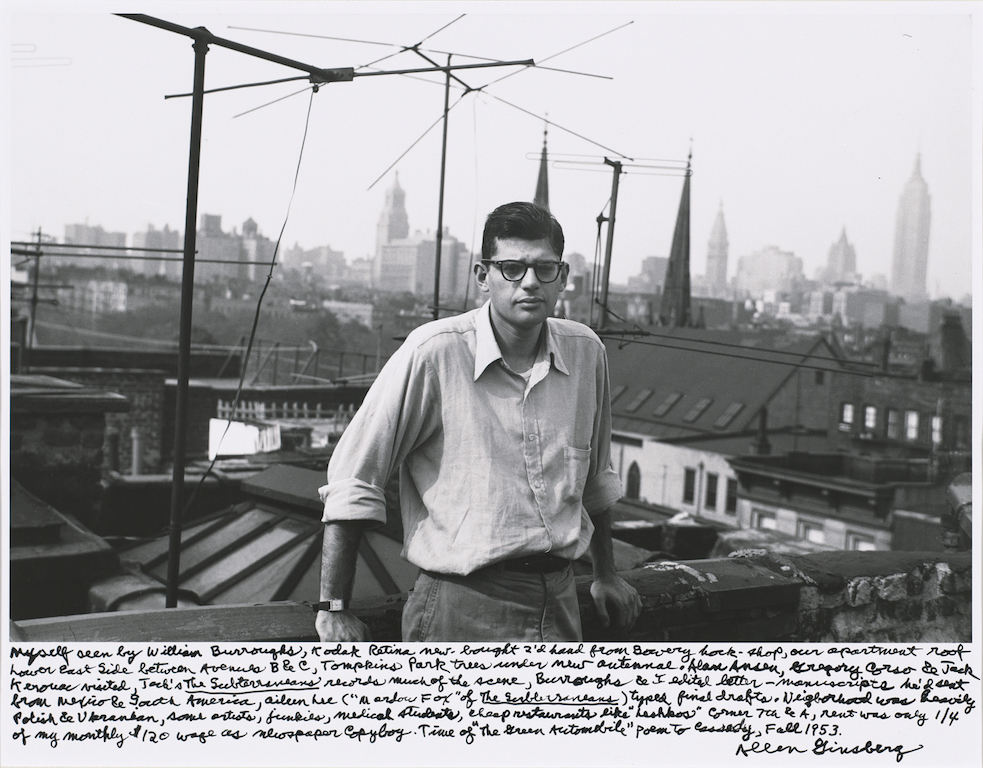

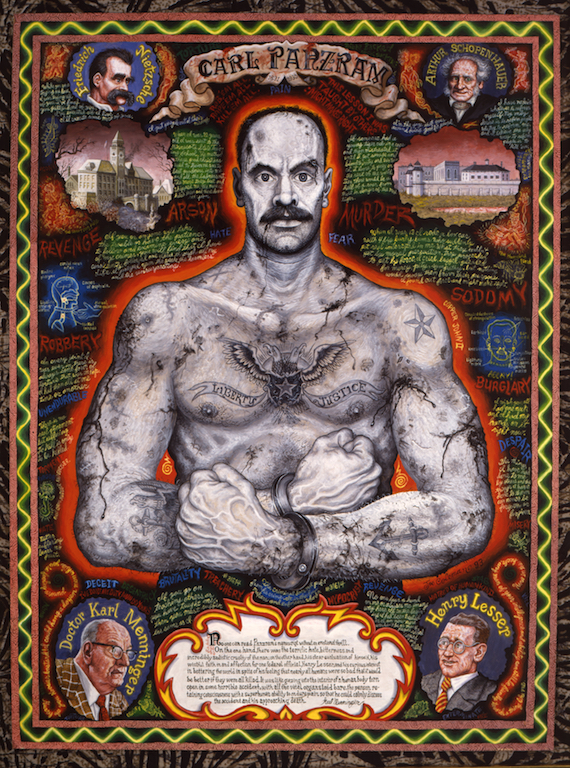

Outlaw art cannot be commodified. Its refusal is too vehement, its esthetic terms too volatile. Artists like Boris Lurie, a Buchenwald survivor who launched the NO!art movement, or David Wojnarowicz who battled on the front lines of ACT UP!, or Annie Sprinkle, who made her body the Bunker Hill of a sexual revolution, or Clayton Patterson, who weathered repeated incarceration over the Tompkins Square Riots to defend the Truth, or Ana Mendieta or Sue Coe or Joe Coleman or Thomas Nozkowski, could and will not be soiled because their art is stamped with refusal and freedom, a rejection of limits and embrace of possibility that strike me as succinctly Outlaw.

While fully aware of the tradition of mainstream art, their art flies in the face of conformity, to express the inexpressible, articulate the unacceptable, or voice the outrage that lies buried deep within the soul under the conditions of modern life. Outlaw artists are, as Sartre said of Baudelaire: “Not revolutionaries but men [and women] in revolt.”

Why art? And why do I call it “Outlaw”?

My mother, a Holocaust survivor, imparted to me the sense that civilization is

not to be trusted; that beneath the surface of seemingly normal existence dwell monsters awaiting their turn. Those whom she saw most willing to defy those monsters were often outlaws — armed partisans, Communists, artists, Zionists, renegade priests, even criminals. One thinks of Samuel Beckett, who served in the French resistance during the war, or Albert Camus, who edited the underground newspaper Combat.

Today, new monsters walk our earth from Trump to Putin and Kim Jong-un. In this strange, hostile world, language is subordinated to digital pyrotechnics. A disaffected population walks facedown in their iPhone screens.

Images, to be meaningful to them, must have the depth of language, the power of “War and Peace.”

In the work of Outlaw artists there is that and more. And though some of these works are probably 50 years old, they still seem freshly avant-garde, works produced in drafty cold-water lofts by artists grappling not just with art but with existence itself. Corrupting art world success has not ruined such efforts. It’s all there still and will be forever: the struggle to be alive, the quest for deeper meaning, the fury and sublime inspiration of the Outlaw Artist.

“The Outlaw Bible of American Art” (Last Gasp), 688 pages, color and black-and-white images throughout, $39.95. Kaufman’s other books include “Drunken Angel” and “The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry.”