After fighting to close the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island during the 1970s and 1980s, Willie Mae Goodman continues to fight for her developmentally disabled daughter — now in her 60s — to get the right treatment in facilities in New York.

Now, with the problems of Willowbrook seemingly far behind, Goodman said there remains neglect from the government in the form of funding. This deficiency manifests itself in the form of a staffing shortage, and she indicated the real victims are residents of groups homes who depend on that care.

“As a parent, I fear that — I always pray to God that he takes Margaret first,” Goodman said. “If I pass away, the service that she gets in there, she wouldn’t get. It’s because I’m involved.”

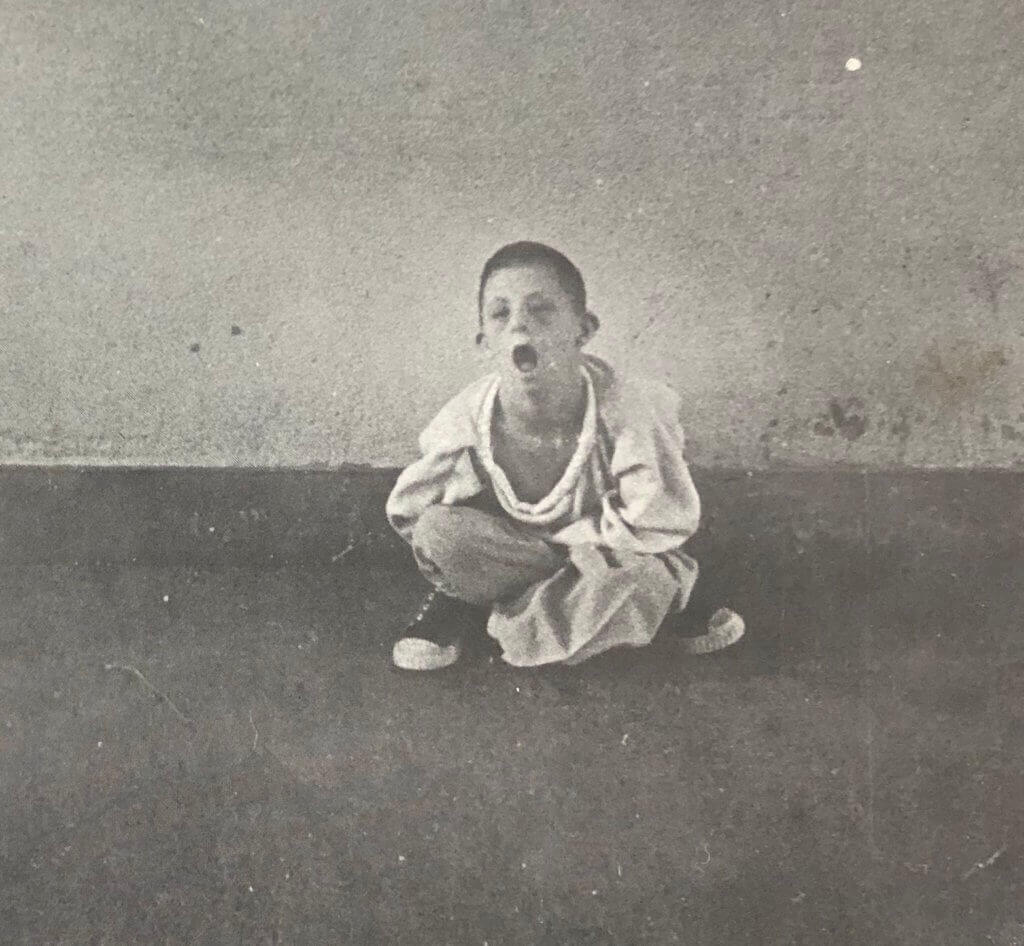

Margaret, due to her condition, cannot communicate and is wheelchair bound. But it’s been a long journey for the mother and her daughter. After the movement to close Willowbrook — with the help of Governor Hugh Carey and activists, along with the reporting of Geraldo Rivera, Margaret was moved into another state school on the Lower East side.

Eventually, 14 care facilities would open up in Manhattan, one of which being just blocks from where Goodman has lived in East Harlem for 67 years.

To Goodman, the Cuomo administration failed to acknowledge the developmentally disable publicly while letting funding stagnate, leaving group homes such as the one on 119th Street in Manhattan where her daughter Margaret lives becoming less maintained and primed for mishaps from overworked staff.

As the funding has stagnated, facilities have struggled to cope with clients living longer than ever before, according to Tom McAlvanah, executive director of the InterAgency Council of Developmental Disabilities Agencies.

“The average age of death for a person with intellectual developmental disabilities was somewhere in the 40s when I started in the field back in the 1970s,” McAlvanah said. “Now it’s just a few years shy of the general population somewhere maybe in the 60s, or 70s. So, because the health care, because we’re putting money into helping support them with good staffing, it’s intensive services. Around the clock services that [Goodman’s daughter] gets, it’s pretty intensive, it’s costly; but it’s the right thing to do as a society and it costs less than an institution.”

At 91, Goodman’s daughter turned 66 on Oct. 26, but at the time of Margaret’s birth, doctors had said she wouldn’t make it to the age of two.

Along with the breakdown in funding, communication between the state Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD), the state and activists like Goodman and McAlvanah has suffered. Goodman recalls commissioners to OPWDD being available by phone in the past and sending staff to handle sensitive matters in prompt manner. That communication has not existed since Cuomo took office in 2010.

There are other parents who feel the same, that we got to a better place and now we’re seeing it slip,” McAlvanah said.

Now, they can only hope that Governor Kathy Hochul brings some sense of peace for parents, especially those who fought close Willowbrook. Things seem to be going in a somewhat positive direction for the activists with the new administration, with former OPWDD Commissioner Theodore Kastner being among officials ousted under the new state leadership.

Where does the OPWDD get it’s funding?

Up to 95% of its 121,000 clients in 2020 had the services of group homes covered by Medicaid, a demographic that has increased 13% since 2014. The OPWDD received up to $8,348,961,777 from Medicaid in 2020, according to data.

The agency says that in recent years, there have been efforts to increase wages for service provider staff in the form of two 2% increases in 2015, two 3.25% increases in 2018 and another round of two 2% increases in January and April of 2020.

Employees of not-for-profit service providers also received a 1% cost of living adjustment increase as part of the 2021-2022 budget, OPWDD told amNewYork Metro.

“As with all human services fields nationwide, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on an already shrinking field of available direct support workers and OPWDD is taking an active role along with our providers of services on finding solutions to the workforce issues faced by our field,” the agency said in a statement. “We recognize that our direct care workforce is the backbone of a strong service delivery system, which is why New York State has made substantial and ongoing investments in wage increases for our direct care workforce over the past several years. OPWDD has an additional opportunity to make investments in our workforce through the one-time American Rescue Plan funding and are currently awaiting final approval from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on our proposed spending plan.”

OPWDD clarified that these contributions to contractors are ultimately allocated at the service providers discretion and are expected to balance it across their organization.

Jose Rivera, an unofficial “son” of Goodman, also had a brother in Willowbrook before it was shuttered in one of the biggest scandals in state history.

As an activist, Rivera says the challenges of the pandemic have only exacerbated the impact of the staffing issues on group homes, not only for the illness on concentrated living conditions of all kinds.

“Those challenges have been made worse over ten-plus years of neglect in terms of state funding,” Rivera said. “Coincidentally the state tends to pay more than the not-for-profits are able to, so the not-for-profits are at a greater disadvantage… They’re doing the same work, by the way.”

Double and triple shifts are worked by direct support professionals to make up for a lack of help in facilities.

“We’re struggling to make sure that the state is providing adequate funding to allow for people to have a decent living wage,” Rivera added. “We’re now paying the piper, so to speak. The fact that there is such a manpower shortage should not be surprising when you haven’t funded these services. This isn’t something someone can choose to access, these are services that people in our communities require.”

In May, state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli issued a report that OPWDD was among three agencies in representing about 25 of the state’s overtime pay to workers. DiNapoli stated that $156 million had been paid out to its nearly 20,000 employees under OPWDD in the year 2020.

According to Goodman, there are only about five of the Willowbrook families who are active in trying to maintain the gains made over the decades. But age is more than a state of mind, and new generation of parents will need to step into their shoes.

Goodman is not certain of whether or not there will be a succession there, with many parents possibly finding unadvisable comfort in the standards won in the Willowbrook fight. Goodman fears her life’s work could be taken for granted.