Transit ridership in the Big Apple continues to languish at around 60% of pre-pandemic levels, even as car and air travel have rebounded almost completely to Before Times rates, according to a new report from City Comptroller Brad Lander.

Average weekday subway ridership in September stood at 61% of the average recorded in September 2019, according to the Comptroller’s monthly economic and fiscal outlook for September. Ridership on MTA buses and Metro-North commuter railroad were both at 64% of pre-pandemic ridership, while the Long Island Rail Road stands at 66%.

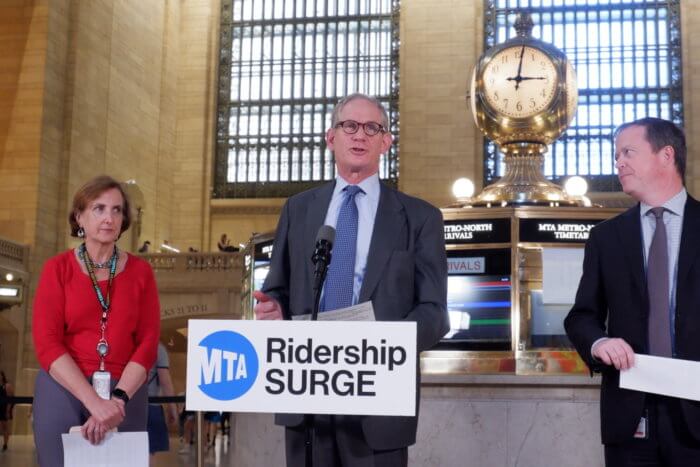

MTA honchos have touted growing post-pandemic ridership numbers showing an increasing return of riders to the system; subways set a COVID-era record of 3.88 million riders on Sept. 21.

But the good times may cease to roll when looking at other statistics in Lander’s report: automobile commutes have almost completely rebounded to 2019 levels, with passages through bridges and tunnels in September at 99% of their numbers in the same month of 2019.

“As the city’s employment reaches near pre-pandemic levels, the shift away from public transportation to personal vehicles puts our commitment to reducing transportation emissions in reverse. In addition, the heightened level of traffic violence has set 2022 to be the deadliest of NYC streets in nearly a decade,” Lander said in a statement to amNewYork Metro.

“If we are truly committed to a post-pandemic recovery that prioritizes the needs of all New Yorkers, we must seriously look at ways to fund a robust mass transit system through congestion pricing to get people back on the trains and buses while strengthening the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program to deter reckless driving,” the Comptroller continued.

Also nearly fully recovered is air travel into and out of the Big Apple: passenger volume at New York area airports last month was just 6% below the same month in 2019. In fact, air travel in the New York metropolitan area is recovering faster than the national average, where passenger volume stands 9% below pre-pandemic numbers.

In July, the number of passengers traveling internationally to and from New York airports crossed the 4 million mark for the first time since the summer of 2019.

The main reason for languishing weekday ridership is the rise of working from home, MTA Chair Janno Lieber has said. With so many former office employees now firmly entrenched in the work-from-home lifestyle, those who once dutifully rode the train to an office in Midtown Manhattan have attuned themselves to filing quarterly earnings reports wearing pizza-stained sweatpants.

Also notable: weekend ridership is at a substantially higher pre-pandemic proportion than its weekday counterpart. This past Saturday, Oct. 8, subway ridership stood at 73.4% of a comparable day in 2019; the next day, it was at 72.1%. That suggests New Yorkers working from home are choosing to take mass transit to their non-work activities, the MTA says, even if they no longer engage in a daily commute.

Where people go on their commute may also have seen a change: earlier this year, the MTA released data showing that in some residential, working-class areas of the city, particularly in the boroughs, transit ridership had rebounded to pre-pandemic levels; in some places it had even exceeded it. The most notable lag has come in office districts with lots of white-collar workplaces, though passenger numbers at those stations are growing.

“Most of the recent ridership surge is attributable to white-collar workers returning to their offices more frequently, along with tourism and school reopenings,” Lieber said at the MTA Board’s September meeting. “[But] I never want to forget the blue-collar and essential worker neighborhoods which have continued to rely on mass transit right through the pandemic, and have grown back to much higher levels than everywhere else.”

Transit leadership has warned that lagging ridership could result in financial calamity once $15 billion of pandemic relief funds run out, which is expected to take place in 2024. In the absence of revitalized ridership or other new streams of funding, the authority could be forced to make painful service cuts, lay off employees, or raise fares in order to cover its multi-billion dollar deficit.

To lure riders back to the system, the authority has tried schemes like “fare capping,” where after 12 rides paid for via OMNY, straphangers can get on the train for free for the rest of the week.

In the longer term, honchos hope to finally implement congestion pricing below 60th Street in Manhattan, which they estimate will bring in billions in new annual revenue. If it goes to plan, the tolls, which could reach up to $23, would reduce automobile traffic in Manhattan’s central business district and increase reliance on a transit system newly flush with cash.