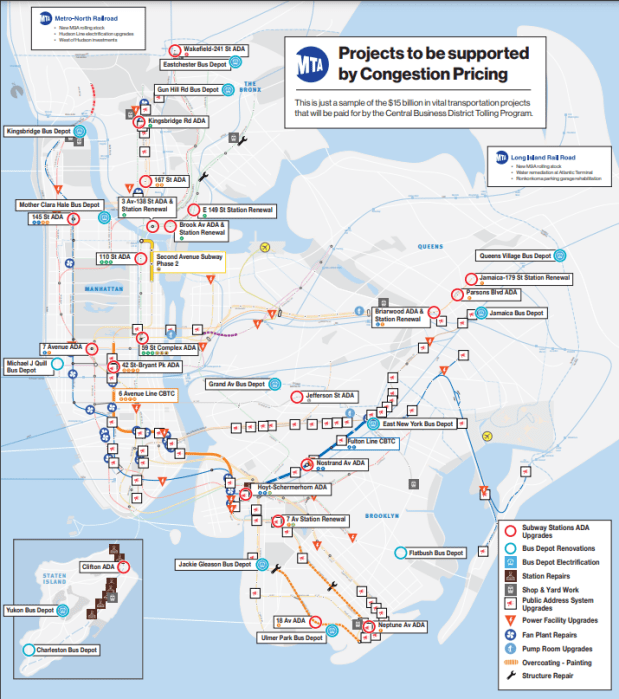

Gov. Kathy Hochul’s eleventh-hour decision to halt New York’s congestion pricing program put a big question mark on $15 billion in mass transit capital improvements the MTA planned to undertake over the next few years, many of which the agency says are urgently needed.

The governor announced on Wednesday that the toll — which would have charged $15 to most motorists entering Manhattan south of 60th Street and was set to begin June 30 — would be indefinitely postponed, arguing that she could not impose an added cost on already-struggling New Yorkers. It was a dramatic about-face for the governor, who until Wednesday had sung the praises of the program — which is intended to reduce punishing traffic in Manhattan and clean up the city’s air.

More to the point, though, the plan would raise billions of dollars for critical improvements to the MTA transit system, which is more than a century old and showing its age. Congestion pricing is projected to generate $1 billion per year in revenue, enough to leverage the issuing of $15 billion in municipal bonds for a huge slew of capital projects.

These projects are, at least for now, in limbo as Hochul considers alternative funding options.

What’s in limbo

Phase 2 of the Second Avenue Subway, extending the Q to 125th Street, is now in limbo, even after the feds agreed to disburse $3.4 billion in infrastructure money to the project. That money was predicated on the MTA being able to pay its own share of the financing — which is dependent on congestion pricing.

Further, the future of the Interborough Express — the proposed light rail line between Brooklyn and Queens that Hochul has described as her “baby” — is up in the air.

The MTA also intended to use the money to replace Great Depression-era analog train signals with modern Communication-Based Train Control, which allows trains to run closer together and has contributed to a surge in reliability where it’s been implemented on the L and 7 lines. The MTA is now unable to re-signal the A and C lines in Brooklyn and the B, D, F, and M lines in Manhattan.

Decades of deferred upgrades to signals were arguably the primary cause of the 2017 “Summer of Hell,” which convinced lawmakers to get onboard with congestion pricing in the first place.

The agency also cannot complete planned upgrades to 39 subway stops and 9 Long Island Rail Road stations to make them accessible for people with disabilities, nor purchase 250 electric buses or upgrade 11 bus depots to be capable of electric charging.

It can’t buy new R211 subway cars to replace aging rolling stock on the rails, some of which date back to the Gerald Ford administration.

There’s also plenty of even less sexy items critical to maintaining the system that would have been funded — painting century-old outdoor subway structures to prevent steel corrosion; repairing ventilation, public address, and water pumping systems; fixing electrical substations serving 15 subway lines; and replacing elevators and escalators at dozens of stops.

All of these projects were expected to support more than 20,000 jobs across the New York region, the MTA has said.

On Thursday, the city’s Independent Budget Office said the abrupt postponement “will complicate the long-term competitiveness of New York City.”

Capital plans in jeopardy

The MTA’s capital plan is distinct from its operating budget, which is funded by fares and government subsidies and goes towards things such as payroll for 70,000 employees and electricity to power the subway’s third rail.

The capital budget, meanwhile, finances long-term construction projects that keep the transit system in working order, as well as those that expand its ability to serve New Yorkers. They include mega expansion projects like the Second Avenue Subway, modernizing train signals, making subway stations accessible for people with disabilities, and replacing diesel buses with electric ones.

Unlike the operating budget, the capital program is funded through debt from bond issues. For the current $55 billion capital plan, most of the bonds were backed by taxes on e-commerce goods and on high-end real estate, but $15 billion was to be backed by congestion pricing revenue, which transit officials also contended would be a stable source of revenue for future plans.

Without congestion pricing, the MTA is not able to complete these projects. Bonds can only be issued against a revenue stream once, and new bond issues must be approved by the Legislature.

That would also pile even more uncertain debt on the MTA’s $50 billion outstanding load, explained MTA researcher Rachael Fauss at Reinvent Albany.

“The only way they can keep the capital plan alive is coming up with another pot of money,” said Fauss. “And it does not appear that there’s a political will to do so.”

Hochul on Wednesday said her administration had set aside money to “backstop” the capital plan, but did not specify how much money there is, or from where it would come.

Manhattan state Sen. Liz Krueger, chair of the powerful Finance Committee, said she is “not aware of what she is referring to or where she believes that money will come from.”

Making up ‘Plan B’

Hochul reportedly wants to pass a new payroll tax increase on New York City businesses to replace the funding, but there appears to be little appetite for that in Albany especially after last year’s bump to rescue the MTA’s slumping post-COVID operating budget. Business leaders have also expressed distaste at any potential payroll tax increases.

As such, transit leaders have said that there is “no plan B” for transit investments should congestion pricing not go through. And since the MTA is not an executive agency but a public authority, there are questions of whether board members would be violating their fiduciary duty to the organization by allowing the governor’s plan to go through.

“I think that if the Legislature doesn’t give them any alternate funding, they can’t exercise their fiduciary duty,” said Fauss. “I can’t see how they square their duty to protect the financial interests of the MTA, which is set in law, with defunding themselves of $15 billion.”

The board is nominally independent but is effectively controlled by the governor, who appoints the plurality of members and largely controls the purse strings. But several board members have publicly expressed shock and dismay at the governor’s move.

Midori Valdivia, one of Mayor Eric Adams’ appointees, suggested in a LinkedIn post that the decision should come to a vote by the MTA Board, which next meets on June 26.

“If you care about jobs — from engineering, construction, and good-paying union jobs, this is the moment,” said Valdivia. “To say I am disappointed is a true understatement.”

The MTA had already inked a $500 million contract to install, operate, and maintain the network of cameras that would levy tolls to enter the central business district. Now, that network is functionally useless.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/