The federal government granted New York City $117 million to design and build part of a High Line-esque “linear park” on an abandoned rail spur in Queens — but some advocates and elected officials worry the plan would forever foreclose the long-sought possibility of reactivating transit service along the corridor.

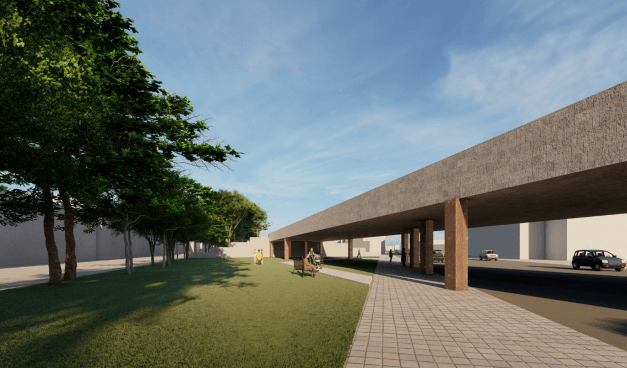

U.S. Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand announced the massive sum of funding for the QueensWay project last week, specifically to build the “Forest Park Pass” section between Union Turnpike and Park Lane South. When completed, the QueensWay will be a 3.5-mile, 47-acre linear park with pedestrian and cycling trails, which proponents say will connect residents to green space in areas between Forest Hills and Ozone Park.

“For many of the 2.3 million people who live in Queens, access to public parks and open space is limited, and in many cases, difficult and dangerous to access by bike or on foot,” Schumer said. “The QueensWay will provide much-needed green space and a new transportation corridor within walking distance of hundreds of thousands of residents and countless small businesses in Central Queens from Forest Hills to Ozone Park.”

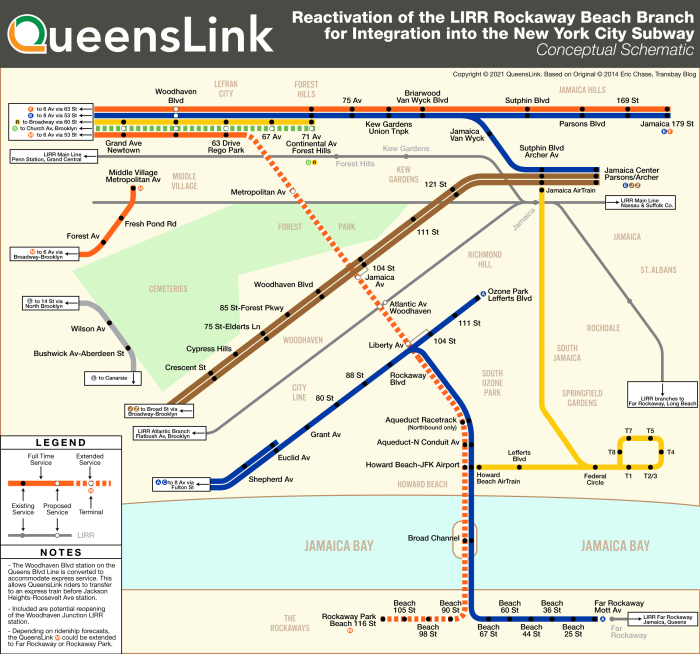

The park would be built along the Long Island Rail Road’s long-disused Rockaway Beach Branch, which once upon a time provided rail service between Rego Park and the Rockaway Peninsula. The southern half is still used by the A train between Ozone Park and the Rockaways, but the northern bit has sat abandoned since 1962 — with the rail infrastructure deteriorating and the right-of-way becoming overgrown with vegetation.

Because the right-of-way is already set up for rail, local pols and advocates have long called for reactivating the branch as a subway line, providing a new commuting option with a wealth of transfers for southeast Queens residents who brave one of the country’s longest commutes, as well as connecting them with the rest of their borough.

That proposal, called the QueensLink, would extend the M train south along the branch all the way to Rockaway. Advocates estimate about 50,000 riders would use the line, and it has support among a diverse set of Queens elected officials from Democratic socialist Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani to conservative Republican Council Member Joann Ariola.

QueensLink supporters say that their proposal would allow for the construction of both a new transit line and ancillary parks along the route, even as the QueensWay would only include parks. They also argue that building the QueensWay now would preclude the city from ever revisiting the QueensLink idea, because, as with the High Line, it would require ripping up train tracks that would be much harder politically to put back in once the park is up and running.

“If the city fails to design both transit and parks together, Queens will forever remain a divided borough and forfeit the economic growth that a new subway line would bring,” reads a March 12 statement signed by “the QueensLink Team.”

QueensLink supporters acknowledge the park would be a “boon for those who live nearby,” but say those living further south will get “nothing” out of the deal.

“These residents, who face some of the longest commutes in the city and lack nearby park space, will have no access to these improvements,” the statement reads. “Meanwhile, residents to the North will still have no convenient way to access the beach or JFK airport.”

Spokespersons for Mayor Eric Adams, a supporter of the QueensWay, declined to speak on the record, but contend that building the linear park would not preclude building transit if the MTA were to determine it is feasible.

In its 20-year needs assessment last year, the MTA estimated the QueensLink project would cost about $6 billion and opted to declare it not worth the money for the additional transit ridership, though QueensLink advocates have argued the MTA overestimates the costs.

But hope is not yet over for the QueensLinkers. In its one-house budget resolution last week, the state Senate included $10 million to fund an environmental impact statement for the transit project; if approved, it would be the first time QueensLink has ever received public money.

“What I’ve learned about government is that it ain’t over till it’s over,” southeast Queens state Sen. James Sanders told Streetsblog. “God willing, you’re able to show them the incredible opportunity to maximize not just that one thing, but to have two beautiful, major things,”

Read more: Historic Tunnel Marks Diamond Anniversary