The Metropolitan Transportation Authority finally released the possible tolls and exemptions for its planned congestion pricing charge to drive into Manhattan’s central business district.

Motorists could have to pay anywhere from $9–$23 to enter the borough below 61st Street and the MTA expects the fee to cut vehicle traffic by up to one fifth.

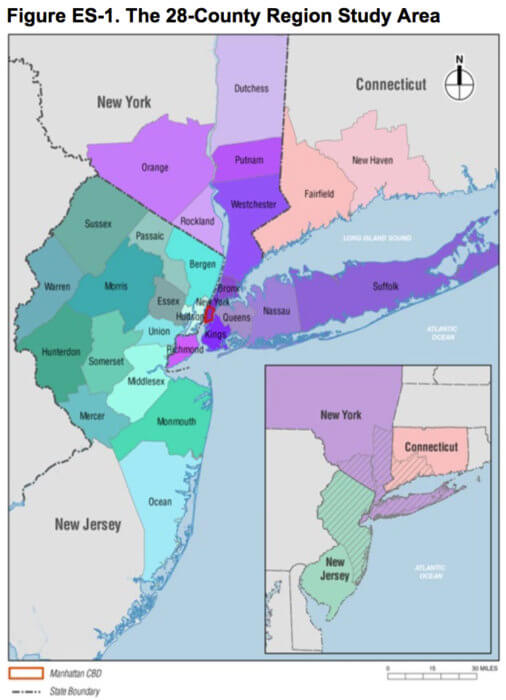

The agency released the details as part of a federally-supervised so-called environmental assessment, in which the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, along with the state and city Departments of Transportation, looked at several scenarios and their effects on New York City and the larger commuter belt.

Senior MTA officials gave amNewYork Metro and other city news outlets an early look at the assessment’s 38-page executive summary Tuesday ahead of its full release Wednesday morning.

The document revealed long-awaited specifics on how the project may shape out once the MTA activates the tolling infrastructure scheduled for late next year or early 2024.

Officially called the Central Business District Tolling Program, or CBDTP, the program is the first of its kind in the United States, but other cities like London, Stockholm, and Singapore have successfully implemented a similar tax on drivers for years.

The MTA expects the toll to bring in about $1 billion in revenue a year, against which transit bigwigs plan to bond $15 billion to fund a large chunk of its five-year capital plan to modernize its aging mass transit system.

The study looked at how the toll could impact commuters from a whopping 28 counties around Manhattan, stretching as far as Connecticut and the suburbs of Philadelphia and affecting 22.2 million residents.

“The tremendous detail included in this assessment makes clear the widespread benefits that would result from central business district tolling,” said MTA Chairperson and CEO Janno Lieber in an Aug. 10 statement.

“Bottom line: this is good for the environment, good for public transit and good for New York and the region. We look forward to receiving public feedback in the weeks ahead,” Lieber continued.

The proposal became law three years ago, but has been slowed down by the pandemic and bureaucratic slogs between the Empire State and the federal government, with Washington most recently demanding answers for more than 400 technical questions and comments.

Transit boosters hailed the program’s progress, saying it was long overdue.

“Congestion pricing and the money it will bring in are critical to the MTA’s capital programs, to signals, tracks, stations, rolling stock — all of the things that riders rely on to get them where they need to go,” said Lisa Daglian, Executive Director of the agency’s in-house rider advocacy arm, the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee. “It’s also critical to reducing greenhouse gases and the intense congestion in the central business district, it will make it easier for buses, emergency vehicles, deliveries, and drivers who do enter the congestion zone.”

Varying tolls

The price of the tolls and their impacts on traffic differ depending on who gets exempt from the charge or receives discounts.

Under the congestion pricing law passed in Albany in 2019, qualifying emergency vehicles and drivers transporting people with disabilities are already absolved of the fee, and residents of the central business district making less than $60,000 can get a state tax credit against the tolls.

The MTA plotted seven different scenarios with exemptions for different classes of vehicles, from cars, motorcycles, and commercial vans, to yellow taxis, for-hire vehicles, trucks, and buses — including the agency’s own transit vehicles.

They also looked at discounts in the form of daily caps, and credits that drivers could get to offset other tolls on bridges and tunnels that directly connect to the Manhattan business zone from the other boroughs and New Jersey.

Those crossings include the Queens-Midtown, Hugh Carey, Lincoln, and Holland tunnels, and the Robert F. Kennedy, Henry Hudson, George Washington bridges.

Without any further carve-outs beyond the law, dubbed the “base plan,” the tolls would be the lowest, set at $9 during peak hours, $7 in the later evening, and $5 overnight.

Those prices rise to up to a high scenario of $23 during the day, $14 in the later evening, and $10 at night.

Trucks will pay more with smaller, single-unit vehicles shelling out anywhere from $12-$65, and larger multi-unit heavy haulers paying $12-$82.

Tolls could also go up during the city’s gridlock alert days, the busiest times of the year for traffic, such as when the United Nations meets and over the holiday season between Thanksgiving and the New Year, according to a senior MTA official.

Exhaustive impacts

The goal of the toll is to discourage driving and reduce congestion in the city’s downtown, moving more trips to mass transit and making it easier for those who have to travel in a private vehicle. Higher tolls mean fewer car trips, though traffic patterns would shift if certain toll bridges and tunnels get credits.

Depending on the height of the price, the assessment forecasts between 15.4%-19.9% fewer vehicles entering the congestion zone, decreasing worker car trips by between 12,571–27,471 a day.

The share of daily truck trips through the central business district would drop even steeper at 55%-81%, or 4,645–6,784 fewer journeys daily.

Officials expect transit ridership grow by 1%-2% compared to pre-COVID levels, however the MTA and other transportation agencies have been struggling to recover their full 2019 daily trip numbers two-and-a-half years into the pandemic.

Less noise and air pollution are also an important goal of congestion pricing.

The number of harmful particulate matter could be cut by 11% in the central business district and nearly 9% uptown, according to MTA.

Taxi travails

One of the main negative impacts of the toll would be the extra charge on taxi and for-hire vehicle drivers, who already pay a fee of $2.50 and $2.75, respectively, while operating at or below 96th Street.

The tolls could reduce the number of miles yellow cabs and ride-share operators drive by up to 16.8%, and would disproportionately affect low-income people of color who predominantly work in those industries.

The extra charges could lead to lost income and some drivers going out of business, however the industry would survive, according to the MTA.

“While this could adversely affect individual drivers… the industry would remain viable overall,” reads the assessment.

The transit agency plans to create a program encouraging cabbies and drivers for services like Uber and Lyft to work for the MTA, and the agency plans to make more professional drivers eligible to provide Access-A-Ride services, which has suffered a shortage of staff.

Next steps

The MTA will hold six virtual public hearings on the environmental assessment at the end of the month, starting on Thursday, Aug. 25.

A six-member panel known as the Traffic Mobility Review Board will look at the feedback and the study to come up with a recommended toll for the MTA board to vote on.

Then, the agency can start setting up the infrastructure at its river crossings and south of Central Park over the coming year.

For more information on the Central Business District Tolling Program and the upcoming meetings, visit new.mta.info/project/CBDTP.