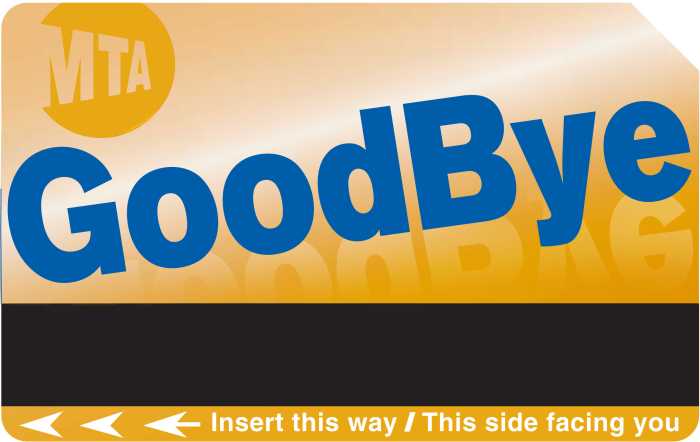

The MTA is moving forward with plans to redesign its subway turnstiles, taking the first steps to procure a replacement for fare gates that officials say are too easy to hop over.

The transit agency on Tuesday put out a “request for information” (RFI) from vendors interested in designing a new, modernized turnstile to replace the one long in use at the city’s 472 subway stations. The RFI solicits firms to present ideas for “secure, accessible, and modern fare gates” that “meet the MTA’s goals for ensuring fare compliance and preventing fare evasion, enhancing accessibility, and improving the customer experience.”

Interested firms must present plans for both “wide-aisle” gates that are accessible for wheelchair users, people with strollers, or anyone else needing extra room, as well as standard turnstiles that are still accessible for people with disabilities, while also being harder to jump over than the existing, low-to-the-ground twirlers.

“The safety of all New Yorkers is my top priority,” Gov. Kathy Hochul said in a statement. “These new fare gates will improve the safety and accessibility of the Subway system, while ensuring riders have an easier time entering and exiting stations.”

MTA officials say the existing turnstile is “too porous” and easily gamed, either by jumping over, “back-cocking,” or simply strolling through the emergency exit gate that’s often opened by passengers arriving at their destination. Agency bigwigs say fare evasion cost the agency $700 million in 2022, a figure that’s grown significantly since the COVID-19 pandemic and could grow larger still.

A number of international firms have already publicly expressed interest in what is sure to eventually be a lucrative contract for redesigning thousands of turnstiles across the five boroughs.

In May, the MTA opened up Grand Central Terminal to showcase firms’ vision for the turnstile of the future, with demonstrations from U.S.-based Conduent, Germany’s Scheidt & Bachmann, and French firms Easier and Thales. All of their proposals were relatively similar, featuring a fare gate that opens middle-out and is far more difficult to scale than the current clockwise twirler.

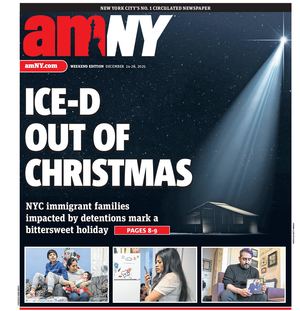

The subway system remains years away from a full-scale turnstile redesign, but fare evasion is a contemporary problem. So in the meantime, the MTA’s answer has been to significantly step up police enforcement. Fare evasion arrests and summonses have skyrocketed this year, with more than 90% of enforcement against Black and Latino riders. Summonses in general have also gone up.

Gothamist reported that overtime expenditures for policing in the subway has increased this year to $155 million, up from just $4 million last year. Late in 2022, the city and state announced funding for 1,200 additional overtime hours every day for cops in the subway system after a series of high-profile crimes underground.

But the issue on the subway pales in comparison to the bus, where MTA officials estimate more than a third of riders do not pay the fare. The answer to the question on buses is not as cut-and-dry as on the subway, though; the MTA has expanded its “Eagle Teams” of inspectors who board buses to check that fares have been paid. Formerly the sole domain of Select Buses, Eagle Teams have been expanded to local routes as well as bus stop “hubs” where many lines converge.