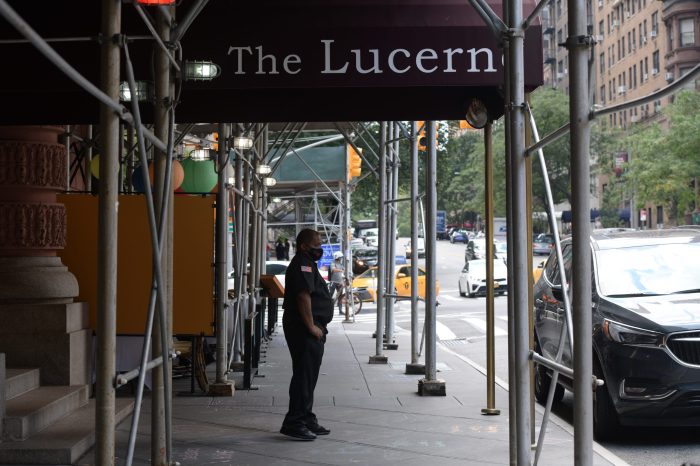

Close to 60,000 men, women, and children spend their nights in the New York City shelter system each evening – including a record number of single adults.

Solving this emergency will require an interdisciplinary focus that goes beyond the way we typically think about and discuss the homelessness crisis and attacks the problem at its institutional root causes. That starts by understanding the ways in which the crisis is linked not just to soaring housing costs but also to our overall system of incarceration and criminal justice.

The good news is that we are starting to see the conversation change. Osborne Association is a member of the expansive United for Housing coalition, which includes more than 90 organizations with wide-ranging expertise in affordable housing and other related issues, including in criminal justice.

The group makes explicit the link between homelessness and institutional touch-points like hospitals, foster care, and incarceration, and calls for robust investment to tackle this crisis, including doubling city housing spending to $4 billion.

The potential for new resources creates an opportunity for the next mayor to make criminal justice reform an essential component of the strategy to end homelessness by providing resources right where they’re needed most: the families impacted by the current system.

The fact is that the current system of incarceration causes an incredible amount of harm to everyone involved. It severs family ties, promotes isolation, makes re-entry into the community nearly impossible for the recently released, and promotes homelessness. Consider that more than 50 percent of all formerly incarcerated individuals released from state prison immediately enter the New York City shelter system—an unstable environment that does not support successful reentry or offer durable pathways to long-term success.

But it does not have to be this way. By providing material support to incarcerated individuals and their families, we can create better outcomes for individuals, families, and communities. For some people leaving prison, ensuring there are housing options and housing assistance will be enough. But in many cases, we must also work with families directly to ensure they have and can offer a strong and stable support system. Many families foster real concerns about welcoming a formerly incarcerated family member back into their home upon their release – a trend that increases the longer the person is incarcerated, accelerates the inefficient prison-to-shelter pipeline, and hurts our city overall.

We need to build programs that provide those family members with the financial support they need to bring another person into their household as well as provide social service support to help overcome any additional challenges. We also need to provide resources to the currently incarcerated and their families to restore and maintain family relationships during their incarceration. This combination will produce dramatic outcomes, including reducing reliance on the shelter system and reducing our homeless population.

This is the work that we do each and every day, particularly in a new pilot Kinship Reentry Program that will conclude at the end of 2021. Through grant funding from Trinity Church Wall Street, the evaluation of this pilot will allow us to build on the structure outlined above and help inform a better, more humane approach to reentry. And it will show us how to do it on a citywide scale.

With a robust commitment to housing investment, we have an unprecedented opportunity before us to think outside of the box regarding both homelessness and criminal justice. Making resources available to provide material support to some of New York’s most vulnerable individuals will not just help us reduce homelessness and promote better outcomes for the formerly incarcerated. It will also help us live up to our ideals as the most progressive city in America.

James S. Rubin is CEO of Meridiam NA and Board Chair of the Osborne Association, a nonprofit criminal justice reform and direct service organization that serves more 12,000 New Yorkers each year.