Over the last ten years, I have spent a large part of my medical career attempting to identify innovative ways to improve care for violent trauma patients. Many are crime victims. I specifically focus on interrupting cycles of violence in individuals and communities by providing targeted care and multi-disciplinary interventions to both patients and at-risk individuals. Importantly, this provides lessons to change how we care for incarcerated individuals like those at Rikers Island. Incorporation of comprehensive supportive services at Rikers to better address underlying causes of both violent trauma behavior and victimization will help incarcerated individuals break the cycle of violence and recidivism.

Rikers Island has a documented history of sub-optimal conditions including reports of neglect, violence, and difficulty accessing medical and mental health care. From my experience with patients who have been previously detained there, the challenges at Rikers often stem from an overwhelmed system with limited resources and capabilities. Add on the psychological trauma incurred by those incarcerated at Rikers, and the result is poor physical and mental health outcomes.

Currently, 55% of the population at Rikers has a documented mental illness, with 20% reported as having serious mental health disease, sometimes requiring psychiatric inpatient admission. Over the past three years, at least 18 people have reportedly died by suicide, drug overdose, and other causes related to mental health at Rikers. In just six months in 2023, there were over 500 attempted suicides and instances of self-injurious behavior.

Short staffing at Rikers has led to many individuals missing their medical appointments, as no one can see a doctor without an accompanying correction officer. In 2021, an individual missed 26 medical appointments over seven months before committing suicide.

Simply put, despite the staff’s best efforts, providing adequate care or support to the individuals housed at Rikers is often impossible.

There needs to be a systematic, multi-level change to the experience of incarcerated individuals that encompasses a multi-disciplinary approach. The model we have established at the Bronx Stand Up to Violence (S.U.V.) program at NYC Health+Hospitals/Jacobi could serve as a model.

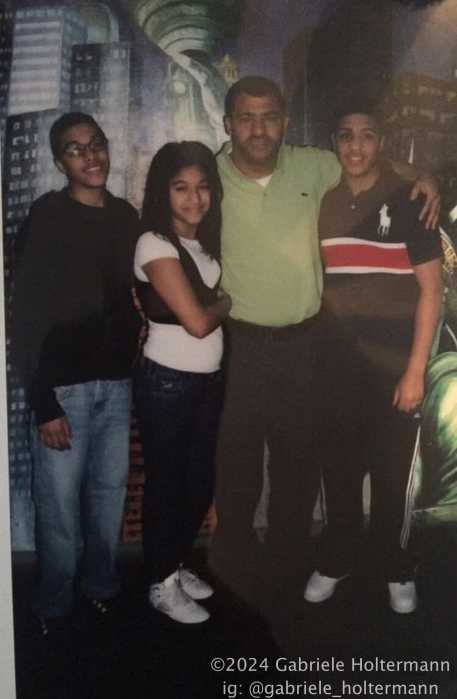

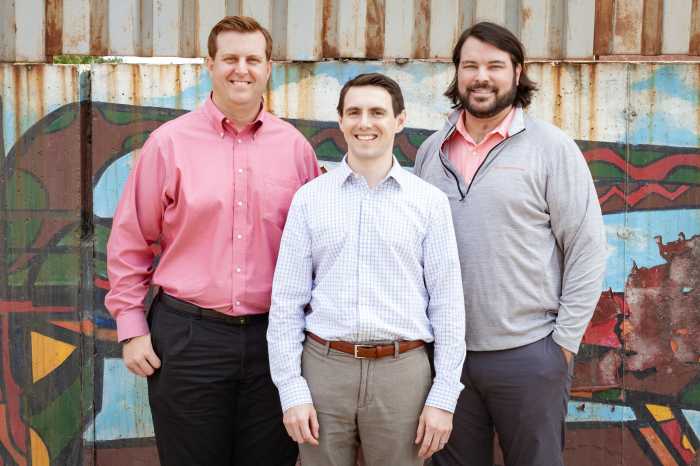

As the medical director of S.U.V., I have seen first-hand how our multi-disciplinary community and hospital-based approach to violence prevention significantly lowered rates of re-injury and recidivism in admitted violent trauma patients. We employ individuals from the community who are credible messengers, some of whom may have themselves been incarcerated, and provide them with an opportunity to be instruments of positive change. These credible messengers function as community outreach workers, hospital responders, supervisors, and mentors to high-risk individuals both in the hospital and the community. Members of our S.U.V. staff provide vital connections for crime and trauma victims to conflict mediation, mental health resources, economic support, job training, housing, and educational resources.

Over its now ten-year implementation, the S.U.V. program has helped break the cycle of retaliatory violence. In designated S.U.V. target areas in the Bronx, we have helped decrease the incidence of gunshot wound victims by 54%, and the rates of re-injury in admitted violent trauma patients by 59%. This success has led to S.U.V. being designated as a model site for possible expansion to other trauma centers statewide.

Now is the time to bring multidisciplinary approaches like these to sites of incarceration like Rikers. So often, people in Rikers were crime victims themselves before their incarceration or suffer violence inside the jails. To interrupt further violence, community-based organizations working inside Rikers could utilize community outreach workers, especially those who have changed their lives after similar experiences, to provide critical services just like the ones offered by S.U.V. The services and connections could continue after release. That will help reduce violence in Rikers, assist people’s transition back into society, and potentially decrease rates of recidivism.

But we should not stop there. Programs like S.U.V. must be part of a long-term, multi-faceted approach to increase access to care and improve outcomes. We need to transition as soon as possible from the sprawling, dysfunctional jail complex on Rikers to a more modern borough-based system to better meet the socio-emotional and medical needs of those held there. Those who have the highest needs could be moved to medically focused facilities, where specialized, tailored care would meet each individual’s unique medical and mental health needs. With dedicated medical staff for smaller groups, the quality of care would improve secondarily to improved availability of medical resources, and more personalized attention would be possible in adequately staffed settings.

In addition, being closer to communities will help ensure that neighborhood-based organizations can reach incarcerated individuals more regularly and help optimize the connection to available post-release services.

Beyond jail beds, we need secure access to mental health inpatient and outpatient resources throughout New York City. This will be a challenge given already existing limited and overwhelmed mental health services, but it is a challenge worth accepting by our city’s political, criminal justice, law enforcement, and public health leadership.

By improving the medical and mental health care available to the most disadvantaged and at-risk individuals, perhaps the cycle of recidivism can be interrupted, resulting in healthier and safer communities for all. This goal is a tall task requiring a multi-disciplinary commitment, but it can start with closing Rikers and transitioning to a borough-based system as soon as possible. Together, we can devise a comprehensive system to better care for some of the most vulnerable individuals amongst us who deserve better. We will all be better off when we do.

Dr. Noé D. Romo is the Director of the Pediatrics Inpatient Service at NYC Health + Hospitals / Jacobi, Medical Director of the Bronx Stand Up to Violence Program, Medical Director of the New York State SNUG Hospital Violence Intervention Programs and is a member of the Independent Rikers Commission.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/opinion/