When the novelist Angela Flournoy first moved to New York over a decade ago, she told her Harlem landlord that she was a writer.

Excitedly, he informed her of a literary landmark just down the block: on 127th Street, the house of Langston Hughes, who wrote of dreams deferred and American possibilities.

So Flournoy made a pilgrimage that a lot of young black writers come to New York to make. “I just went to stand in front of it,” she says. “It certainly looked like it could have used some cheer.”

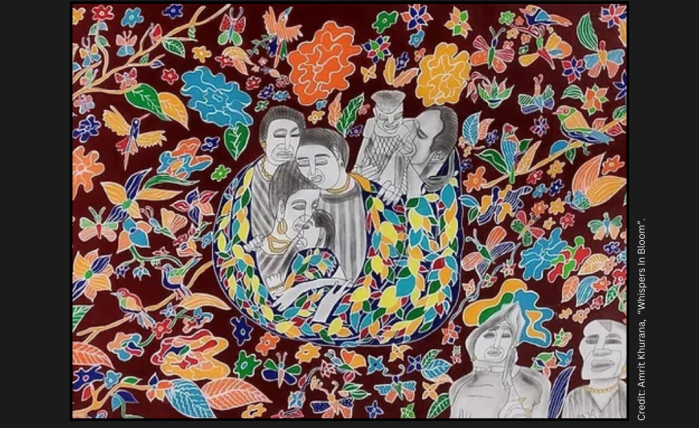

She wasn’t alone in that belief: in July of 2016, children’s book author Renée Watson launched a campaign to preserve the house where Hughes lived for twenty years and open it to the public, so Hughes would have an enduring presence in the neighborhood whose bard he became. The campaign succeeded, crowdfunding $150,000 to lease the historic brownstone, and the house opened as the I, Too Arts Collective on Hughes’ birthday on Feb. 1 of last year.

A new neighbor with big shoes to fill

Since then, the collective — named after a line from one of Hughes’ more famous poems — has tried to make the house a welcoming center for Harlem and New York artists, which might have made Hughes proud.

The poet came to New York in the years after WWI for classes at Columbia, which he left before graduating.

He was a footloose artist, traveling the country and even spending time in the Soviet Union. But “Harlem was just his heart” says the collective’s program director Kendolyn Walker.

The house on 127th Street was shared by Hughes and family members from 1947 until Hughes’ death in 1967. Hughes paid for it largely through his artistic success, with the windfall from his play “Street Scene,” and the house played host to his continued artistic career. Visitors can view his typewriter, and the piano where Hughes wrote and played — he even at one point wrote a song for Nina Simone.

Hughes was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, as mentor and magazine editor and writer, and the house’s location is a fitting homage to that era, Walker says. It’s in the middle of the block in the very center of Harlem, its structure mostly undisturbed since Hughes lived in it.

Walker says that neighbors sometimes wander in and see the wide unbroken main floor, marvelling at what the area’s housing stock looked like before floors got broken up into smaller rooms. Hughes and his aunt and uncle had tenants when they owned the house, and relatives of those tenants have returned for a look as well.

The local community was important to Hughes, Walker says, noting that the writer tended a small (vanished) garden in the front of the brownstone with neighboring children. And his writing was imbued with the spirit of African-Americans struggling in and around the city at a time when much writing about African-Americans followed upper class characters and concerns, Flournoy notes. Today Hughes is the bard of elementary school memorization and hopeful endurance, but at the time he was radical for his portrayal of his peers often ignored by other writers.

Trying to connect to the neighborhood

Coming up on the anniversary of their first year at the site, the collective has tried to replicate that community spirit, bringing the neighborhood and wider city to Hughes’ home. In an already-storied neighborhood, it’s not an easy task: “Harlem’s bigger than I thought,” Walker says.

The group has tried to open its doors when staff is available. The first floor is open to the public three days a week. The collection of Hughes material is small but interesting to quickly peruse. And there are poetry salons every third Friday of the month; every third Tuesday, “Semple” happy hours named after one of Hughes’ fictional characters, the Harlem barfly Jesse B. Semple. The building hosts workshops and art intensives for students and adults, plus outside events open to the public, such as an upcoming celebration of Penguin Classics’ republication of Hughes’ first novel, “Not Without Laughter.” It’s the story of a provincial youth peering at life in the big city — not New York, though Hughes had already put down roots here and would continue to for the rest of his life.

Flournoy, who wrote an introduction to the new edition, will be speaking at the event at the old house on Wednesday. This time, she’ll be inside.