I got into Stuyvesant High School because I bought a Kaplan book and studied for the Specialized High School Admissions Test.

It was a hard test and doing well on it was the first concrete goal I ever had. I remember there being nice but hot weather the summer before the test, and that I would have liked to go to the beach or play baseball in Marine Park. But I stayed home, closed the door and did practice tests. The hum of the air conditioning was quiet and I lost myself in multiple choice questions. I was surprised to find the test-prep vaguely interesting, like a puzzle. I worked hard, I became disciplined, and then I got in.

Actually, come to think of it, I didn’t buy the Kaplan book. My parents bought it for me. I remember it being weirdly expensive, way more than any book I’d ever received. I was in the bookstore with my parents and wanted to buy yet another Star Wars hardcover. They bought me that, but also the Kaplan book.

Also, I didn’t study unprompted. My parents mandated progress. One more chapter. One more, and then you can go outside.

Now that I mention it, I don’t think I was all that good at the test questions at the beginning. But my mother, a math teacher, had a blue shoulder bag of “manipulables”: toys, essentially, that she used to explain concepts in geometry and probability. The blue bag was always in the foyer, as if she might need it at the last minute while escaping a fire or running late for work. My father, who taught English, discussed the books I was reading, even (despite his love of realism) the Star Wars spin-offs. When I got stuck on a test-prep problem, they were happy to help and had time to do so.

But back to my trajectory: I worked hard, and then I got in. I attended one of those middle schools where they passed around 10-page test-prep booklets a week or two before the Specialized High School Admissions Test, then shrugged and said good luck. Lots of my classmates didn’t know what the test was or that you could go to a high school that wasn’t Midwood or Madison. This thing isn’t exactly wonderfully advertised. But I did well on the test as did a bunch of my friends, fellow strivers.

It’s funny though: All those friends had parents who bought the test prep books or were extremely serious about grades and school. Funnier still, I knew those kids from being in the same gifted-and-talented classes since kindergarten. And actually, our middle school had a gifted program, too. We had some teachers, often lifers, who really cared. It was pretty stable and pretty safe.

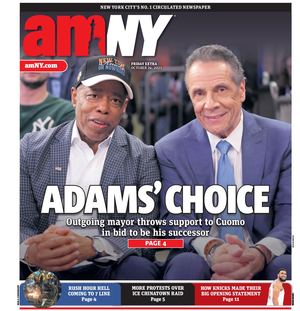

I’ve been thinking about these trajectories and caveats and the stories we tell ourselves about our successes and failures, since Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed eliminating the test that is the sole means of entry to Stuyvesant and seven other specialized schools. In the test’s place, he’d like the State Legislature to create a process by which seats are reserved largely for the top 7 percent of each middle school, as defined by grades and state tests and perhaps other factors that may emerge down the road. The main point is to even out the racial disparities in specialized high school admissions, which are stark: Stuyvesant’s incoming freshman class of more than 900 students, for example, includes 10 African-American students.

The proposal has lots of people in a tizzy because there will be winners and losers. Among the biggest losers — with fewest alternate options — might be the Asian-American test-takers, many of them first- or second-generation immigrants, often from families with incomes below the poverty-line, who grasp at the test as a clear, explicable means out of the city’s worst educational morass. They represent a sizeable group. Stuyvesant is currently 73 percent Asian from a variety of countries and 41 percent of its students are defined as in poverty, a fact that’s easy to forget.

De Blasio’s critics have questioned whether there will be new ways to game the system, not to mention how the test change does little beyond symbolism to alter the instruction in woefully underfunded or unsuccessful elementary and middle schools around the city.

But it’s worth remembering that few and far between is the Stuyvesant or Brooklyn Tech kid who didn’t have some form of help to make their schools, help that wasn’t available to other New Yorkers with complicated home lives, whose parents were less aware of test dates or had less of an appetite for test prep, while the students were stuck in desperate middle schools that didn’t make other options particularly obvious, to name a few disadvantages. Maybe the admissions change will be the help or at least the belated chance those students need.