By their nature, are police vice units inherently at risk for corruption and misconduct?

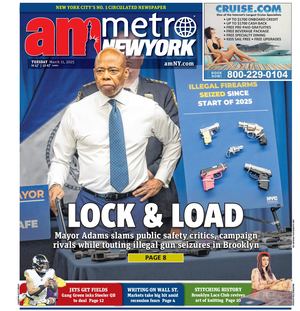

Consider recent revelations at the NYPD:

- On Sept. 13, retired vice Det. Ludwig Paz was charged with running a prostitution and gambling ring.

- In November 2017, a sex worker died while attempting to flee apprehension by vice officers in a raid on a massage parlor. The Queens district attorney’s report on her death offered no critical introspection on the impact of vice operations, labeling her a “criminal” who “engaged in a degrading and humiliating profession.”

- In June 2017, the Daily News reported that a vice officer faced disciplinary hearings after he allegedly had sex with women whom he later arrested on prostitution charges. The public still doesn’t know what, if any, disciplinary action was taken.

As lawyers who exclusively represent people charged with prostitution in NYC, we are not surprised to hear allegations of misconduct and corruption within the Vice Enforcement Unit, the primary enforcement arm of New York’s prostitution laws.

For years, the vice unit has operated with impunity. Time on the vice squad was the perfect training camp for Paz’s post-NYPD career as an alleged brothel owner. Indeed, this unit encapsulates many of the problems public defenders see daily. The NYPD targets marginalized communities, fails to improve community relationships, and hides mistakes and improprieties behind the blue wall of silence.

Our clients describe undercover officers exposing themselves, as well as grabbing clients’ breasts and buttocks, showing them pornography, calling them after arrests, and forcing them to dance provocatively while removing clothing. They also report being provided alcohol, and most disturbingly, having consensual and nonconsensual sex with officers.

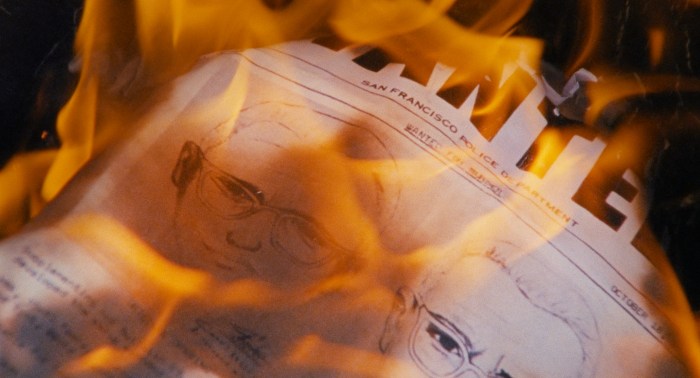

For decades, undercover officers have posed as “johns,” persuading arrest targets to exchange sex acts for a fee. Once an agreement is made, the undercover officers notify their backup team, which makes the arrest. The identity of the undercover officer is always protected.

The NYPD has refused our requests for transparency about its ethical guidelines. We and others in the field have reported misconduct to the Internal Affairs Bureau, district attorney’s offices, and Insp. Jim Klein, commander of the vice unit. We’re still waiting for an answer.

We call for an investigation into the practices of vice and to make public what undercover officers may and may not do when conducting a prostitution arrest. We ask that vice re-evaluate how community complaints are addressed. Finally, we call for an independent body that investigates and prosecutes sexual misconduct and allows complainants to come forward anonymously.

It is time to listen, to #BelieveHer, and to reform vice.

The writers work with the Exploitation Intervention Project at The Legal Aid Society.