“These suicides have been ridiculous.”

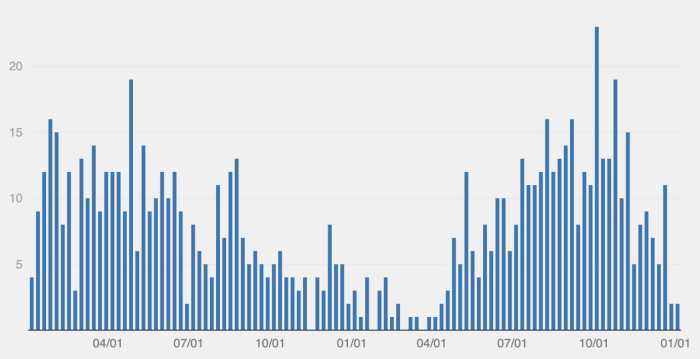

That’s what a retired NYPD lieutenant said of the nine officers who ended their lives this year, a disturbing high with consequences across the 36,000-member force, and lessons for law enforcement around the nation.

The lieutenant, medically retired due to an on the job injury, spoke on the condition of anonymity to talk candidly about the suicides. A lack of candid talk about the issue is at the heart of the problem, the lieutenant says. The mayor and police commissioner can plead with cops to ask for help and access various social programs. That doesn’t help the perceived stigma for officers who admit they’re struggling.

Not when cops are concerned that disclosure can threaten their careers. Not when there is a culture of sucking it up and silently suffering.

The lieutenant laughed a little bitterly about some of the department’s previous mental health campaigns. Like when they plastered the slogan “r u ok?” on precinct flyers and computer screens. It became the biggest joke, she said, a sign of the divide between brass and the ranks: “Great idea, not gonna cut it.”

We’re talking about a job where day to day, officers might encounter assaults, rapes, hideous injuries, deaths. Some cops numb themselves with alcohol or even drugs, says the lieutenant. Maybe a drink is self-medication, or loosens things up so you can talk about what’s going on in your head. But then you’re left without help, just a hangover.

The lieutenant had a friend in the department who killed himself. He had less than five years on the job.

What can be done? The NYPD has established a health and wellness task force. The department has come up with initiatives like a peer-support and training program, plus an app providing easy links to emergency mental health services on departmental cell phones. There also has been a push to make health care easier to access, though that requires people to actually access it.

The lieutenant suggests requiring all officers see a mental health professional once a year as not to single out any one. Officers inclined to treat it as a joke will do so, but for those who need it, “they’re gonna be so relieved,” the lieutenant says. Then there could be a way to continue talking confidentially. It would be a logistical lift for the nation’s largest police department, but mandated training is part of life for cops.

Another reason why cops who may need help don’t seek it is for fear of their NYPD guns and badges being taken away, which is sometimes done for their and others’ safety. But the lieutenant notes that cops without gear may be stigmatized. What if there’s a way for officers to retain badges while they go about duties that don’t necessitate their weapons, so it’s less obvious to peers that someone is dealing with mental health issues (some non-street police work is done without guns)? That’s also logistically difficult as flashing a badge in public, off the job or not, might put a cop in a situation where a gun is needed, but maybe there’s a way forward.

There are other ideas out there, to match the varied reasons cops might be driven to suicide or depression, including the end of a career. Retired NYPD transit chief Joe Fox, now a life-coach and a chief of staff at security company SilverSEAL, says that officers who are about to retire get financial counseling. Why not do the same for wellness?

It can be a difficult day when you get the bland letter from the department at age 62 saying you’re a year away from mandatory retirement. Fox wondered whether this could be done “face to face,” someone high up in the department, maybe even the commissioner, meeting briefly with the member around his or her 62nd birthday.

"The NYPD has a moral imperative to explore all options to support the mental health and wellness of members of service," says Det. Sophia Mason, an NYPD spokeswoman, in a statement. Mason says the new health and wellness task force "will consider all thoughtful input" on the matter.

Fox and the lieutenant both thought the police unions could also play a role in enacting some of these changes. That would be a different tack from the blunt message delivered by Police Benevolent Association head Pat Lynch in an August video message to cops contemplating suicide: “Don’t fucking do it, come on. It solves nothing,” he said in part.

The lieutenant called this "not helpful." Maybe it’s an attempt to speak in direct language, but you can’t just yell at people not to kill themselves. That’s just screaming.