By Jacquelyn Kilmer

In his State of the State address on Monday, Governor Andrew Cuomo closed on a hopeful note, listing a series of our achievements as a state in the face of people telling us “it can’t be done.” One of the achievements he mentioned was ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Surprising, since we haven’t ended the epidemic yet.

We have made steady progress since the Governor’s Blueprint to End the HIV/AIDS Epidemic was unveiled in 2015. In New York City, once the epicenter of the AIDS crisis, new HIV diagnoses were down 8% from 2018 to 2019, and 70% since 2001. These are impressive numbers, but progress has been uneven across communities, and we need to do more to ensure the remaining Ending the Epidemic efforts are carried out equitably.

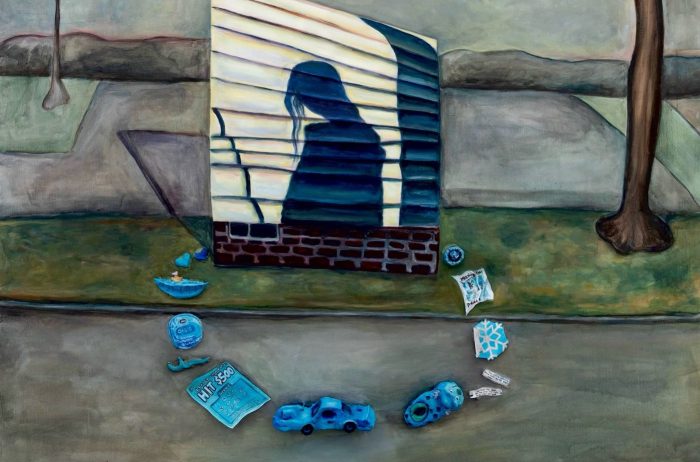

COVID-19 offers us another hard look at the persistent health disparities that cut across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines. The same communities that have been devastated by the pandemic have experienced slower progress towards our Ending the Epidemic goals. In 2019, of all the new HIV diagnoses in New York City among men who have sex with men (MSM), 80% were Black or Latino. 50% of New Yorkers newly diagnosed with HIV in 2019 live in high-poverty neighborhoods. Clearly, there is still work to be done.

The Governor’s rhetoric during the State of the State about addressing health disparities and his stated goal of ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York don’t align with the New York State Department of Health’s plan to change how Medicaid recipients access their pharmacy benefit.

The proposal would “carve-out” the pharmacy benefit from Medicaid managed care plans and move it under a one-size-fits-all bureaucracy managed by the state. This would disrupt care, causing uncertainty for the most vulnerable New Yorkers, particularly those in low-income communities of color and those living with chronic conditions like HIV.

States like New York justify the carve-out based on the belief that the bargaining power of the state, negotiating on behalf of millions of Medicaid members, can lower prescription costs and get a higher drug rebate rate from manufacturers. But studies suggest this isn’t true. The Menges Group recently released a report examining the impact of implementing the pharmacy carve-out in New York. According to the report, the carve-out is highly likely to result in large-scale increases in Medicaid costs. The study estimated that the switch would cost New York State $195 million during the first year of implementation and $1.9 billion during the first five years.

The results would be catastrophic for safety-net health providers, like community health centers and hospitals, who would no longer be eligible for pharmaceutical company discounts, known as 340B revenue, when purchasing medications for their patients. Instead, the state would be taking this revenue directly. This is akin to robbing Peter to pay Paul.

This would cost providers an estimated $250 million annually, forcing them to lay off frontline staff and cut services to the most vulnerable New Yorkers. The timing of this shift is particularly egregious as providers are trying to meet the challenges and fallout of the COVID pandemic, and are being relied upon by the state to distribute the COVID vaccine in the hardest hit communities. Community health centers play a crucial role in the Governor’s plan to vaccinate those disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

The communities they serve are suspicious of the health care system in general and medications and vaccines in particular. Providers must have the ability to spend time talking to their patients about the vaccines, listening to their concerns, answering questions, building trust and encouraging them. While there is reimbursement for administering the vaccine, there is no reimbursement for the time spent in those conversations. Revenue from the 340B program will be essential to allow providers to spend that critically important time with their patients.

The arguments supporting the carve-out are based on faulty math, and the policy change is nothing more than a cynical revenue grab. For a change that will result in certain disruption to the health care system and harm to safety-net care, this attempt at dubious savings is penny-wise and pound foolish. New York can end the HIV/AIDS epidemic and tackle health disparities in communities of color, but only if those efforts aren’t being undermined by the Governor and the Department of Health.

Jacquelyn Kilmer is the CEO of Harlem United.