Summonses for fare evasion this week were nearly double what they were in the same period last year as the city and state flood the subway system with cops, MTA Chair Janno Lieber said on Monday.

Fare evasion summonses were up 81% this week over the same period last year, with more than 1,500 people cited for jumping a turnstile, while total quality-of-life summonses are up 118% and arrests are up 95%, an MTA spokesperson said. Lieber has justified the crackdown and “omnipresence” of cops by arguing they lead to both more apprehension of suspects and more deterrence against lawbreaking.

“It’s deterrence, it’s faster apprehensions, and it delivers the public a greater sense of confidence in safety in the system,” Lieber said at an Oct. 31 press conference at Grand Central Terminal. “What our riders tell us in surveys, the number one thing that makes them feel safer is to see a uniformed officer. We’re delivering that, and we think it’s starting to have positive effects.”

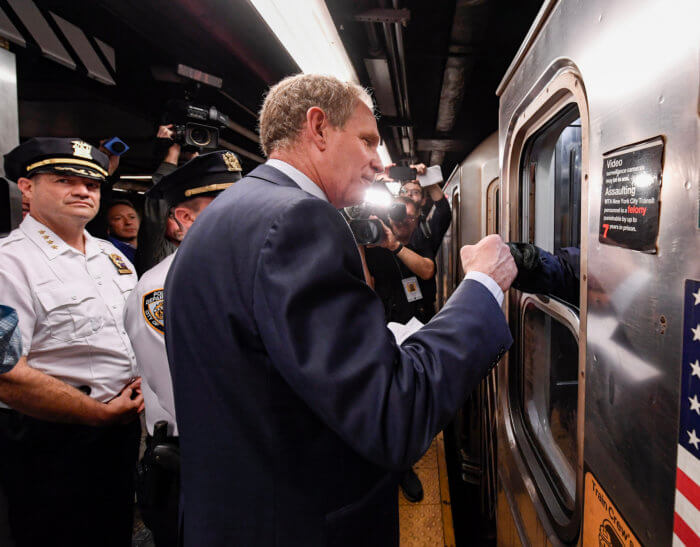

Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul announced the surge last week amid one of the subway system’s most violent months in memory, with the state paying for 1,200 additional daily overtime shifts for NYPD and MTA Police officers in the aim of having cops patrolling more than 300 stations at a time during peak hours. The agency has also tasked train crews to announce to passengers if police officers are present in a given station.

The MTA is also beginning to bring on unarmed security contractors to stand at turnstiles as a deterrent against fare evasion, and to act as “eyes and ears” to help cops catch bad guys. The authority is onboarding about 50 guards per week, Lieber said, and deploying them to major stations facing consistent issues of fare evasion.

The guards, who lack the authority to detain suspects, will be stationed near emergency exits to deter “opportunistic” fare evasion like walking through an open exit door, or to stop scams like breaking vending machines and selling swipes. Should someone jump the turnstile in their presence, they can notify the NYPD, either by alerting the ticket booth or nearby officers.

Lieber says that heavier enforcement against fare evasion prevents higher-level crimes, positing at the MTA board last week that “not every fare evader is a criminal but…virtually every criminal is a fare evader.”

“That is part of the strategy,” Lieber said Monday. “Once they stop someone for fare evasion, they’re checking warrants, and it’s leading to the recovery of weapons very successfully.”

Nine people have been murdered in the subway system so far this year, with three of those murders coming just in October. High-profile incidents of random attacks, like sucker punches, stabbings, and shoves onto the tracks, have left many straphangers on edge.

But the jury remains out on whether enforcing low-level offenses like fare evasion actually deters and prevents violent crime, with many advocates deeming fare evasion a non-violent “crime of poverty.”

Historically, New Yorkers stopped for fare evasion have disproportionately been people of color: a 2017 report from the Community Service Society found 90% of those arrested for jumping a turnstile were Black or Latino, and arrests were heavily concentrated in neighborhoods of color. Two years later, the Daily News found the rate to be 86% Black or Latino.

“It’s needle in a haystack policing,” said Danny Pearlstein, a spokesperson for the straphanger advocacy group Riders Alliance. “They may occasionally find someone who was gonna commit a crime. But overall it’s a distraction from the work of keeping platforms and trains safe.”

Lieber says that the crackdown could continue indefinitely until crime is down in reality and in perception. Earlier this month, a poll from Quinnipiac University found New Yorkers’ most pressing issue in the upcoming race for governor is crime, and the issue has come to dominate that race.

“The MTA is not gonna stop until both the perception and the reality of safety in the subway system is corrected,” Lieber told reporters. “New Yorkers need to know that when they’re going about their business — they’re going to school, they’re going to work, they’re going to job interviews, they’re going to healthcare — that they are not at risk of being the victims of crime.”