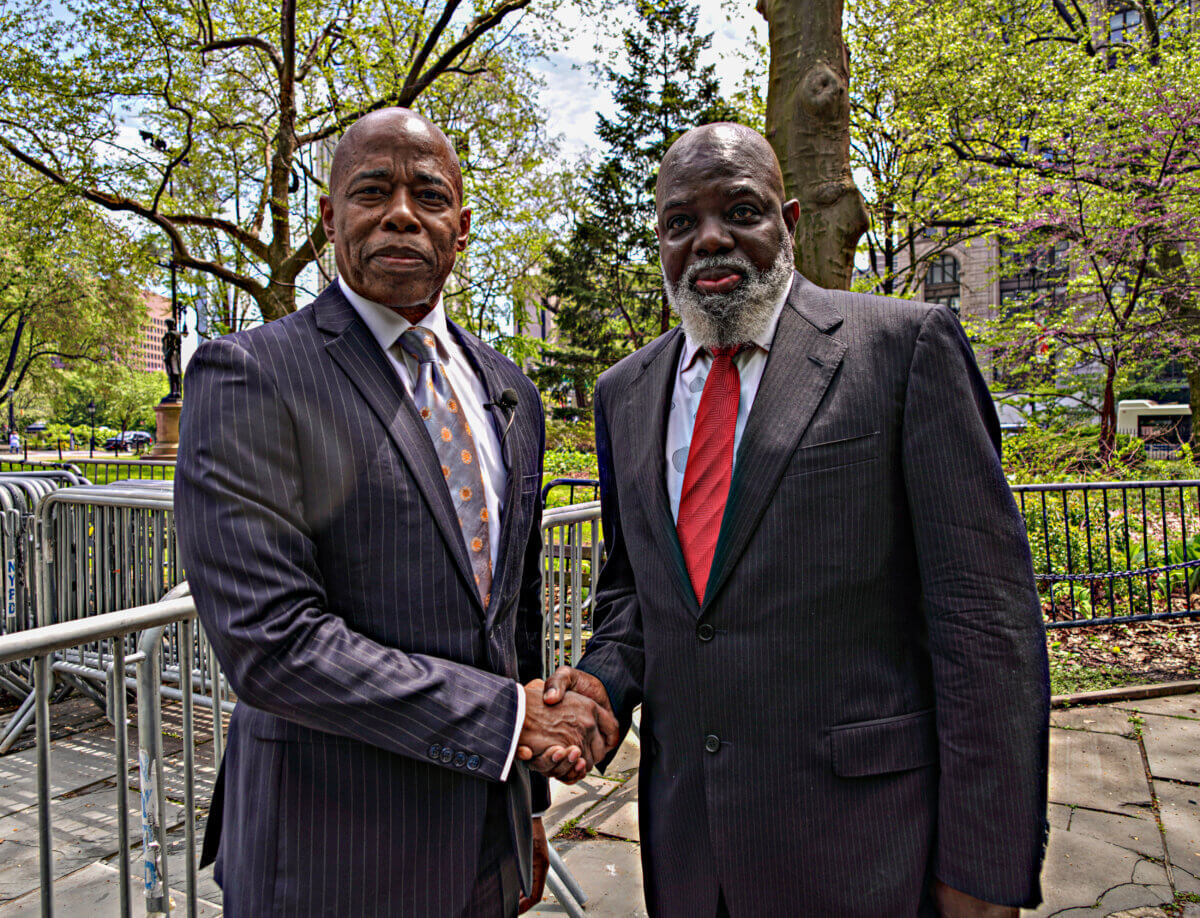

Edward Caban, the NYPD’s acting commissioner following the resignation of Keechant Sewell, brings with him three decades of experience on the force — but also a series of misconduct complaints.

Caban, who had been serving as first deputy commissioner, will remain chief on an interim basis until a permanent replacement for Sewell is named, which Mayor Eric Adams said will take place within the new few weeks. Caban could ultimately get the permanent nod, though that’s not a certainty.

Regardless of whether he becomes permanent commissioner, Caban has the distinction of being the first Latino to lead the NYPD, acting or otherwise.

“Until we name a permanent replacement, Eddie Caban has taken the helm as acting police commissioner,” Hizzoner said in a July 1 statement. “Commissioner Caban is a consummate professional with over three decades of service in the NYPD. I know the hard-working men and women of our city’s police department have a strong leader in place until a more formal announcement is made in the coming weeks.”

Caban joined the NYPD in 1991, following in the footsteps of his father Juan, who served as a Transit Police detective and as president of the Transit Police Hispanic Society. He began his career as a patrolman in the South Bronx and steadily rose through the ranks, getting promoted to sergeant in 1994 and lieutenant in 1999 before landing a position as captain of East Harlem’s 23rd Precinct in 2005.

He moved immediately north to head the 25th Precinct the following year, becoming a deputy inspector in 2008 and a full inspector in 2015. Prior to joining the department’s top ranks, he served as adjutant of the Brooklyn North patrol borough.

Caban was named First Deputy Commissioner, the NYPD’s second-highest post, in early 2022 by Mayor Adams. In that post, he has focused on policy development, personnel management, recruitment, training, and supervision of discipline, according to the department.

But despite that, Caban himself sports a history of discipline and alleged misconduct within the department.

CCRB complaints

In March 1997, the Civilian Complaint Review Board, a police watchdog agency, substantiated charges against Caban, then a sergeant, that he had abused his authority by failing to provide the identities of two officers to a woman seeking to file a complaint against them. Caban received “command discipline,” which means the matter was resolved internally at the precinct — in a manner not subject to public disclosure — instead of going through the formal departmental disciplinary process.

Nine years later, then-Captain Caban of the 23rd Precinct was hit with a slew of misconduct charges related to a stop-and-frisk incident against an unnamed man in East Harlem.

The man was standing on the street at 1:20 a.m. on Aug. 4, 2006, waiting to pick up his daughter from her boyfriend’s house, when Caban and two other officers pulled up beside him in their patrol car and started questioning why he was there. The man refused to identify himself when questioned, telling Caban it’s a “free country” and he could stand on the sidewalk without explaining himself, questioning what he had done.

According to the man, Caban then said “motherf—ker I asked you nicely, now I’m going to have to do this the hard way,” as well as “I am a f—king Bronx Puerto Rican and I don’t take any s—t.” Caban then allegedly pushed the man face-first into the patrol car and hit him in the lower back, in a move described as an “open blow” to the spinal column. Caban then allegedly kicked the man’s legs apart and cuffed him.

When the man complained of being hit, Caban allegedly told him he was “getting ready with the broomstick,” an apparent reference to the infamous 1997 incident when Abner Louima was savagely beaten by several police officers and raped with a broken broomstick.

Rifling through the man’s pockets, Caban — who repeatedly called the man a “motherf—ker” — found his ID and allegedly exclaimed, “this is why I’m arresting you, you don’t live in this neighborhood.”

When the man complained that Caban’s behavior was akin to a “totalitarian state,” Caban allegedly replied, “yes, there they would have cut your f—king head off, but I’m not going to do that just yet.”

Later, Caban claimed that the man he arrested had fit a preexisting pattern of “black or Hispanic males who were 5’6” to 5’8” and between 160-180 pounds and were committing robberies in the area.” The captain said that coupled with the man’s evasiveness in answering questions, he “feared for his safety” and arrested the man for disorderly conduct.

In 2006, over 500,000 people were stopped by the NYPD, often on flimsy pretenses; 90% of them were found innocent. Approximately 82% were Black or Latino.

Caban was nonetheless cleared by the CCRB of most complaints lodged against him for the incident, with the use of force allegation and broomstick threat deemed “unfounded.” But the watchdog did substantiate a complaint that Caban had issued a “retaliatory summons,” for which he was punished with “instruction,” wherein a cop is retrained on proper police procedure.

After sitting in a holding cell, the man was released with a summons for disorderly conduct, under the guise that he had congregated in a public place and refused to comply with orders to disperse. Caban allegedly admitted he arrested the man just to see if he had open warrants, and even told him the ticket was “bulls—t” and accurately predicted it would be dismissed by a judge. The man refused to shake Caban’s hand as he left the cell.

In 2011, Caban was fined $428 and docked 20 vacation days for using a department vehicle and EZ-Pass for personal reasons, and for transporting civilians in a police vehicle without authorization.

Caban’s record also includes a 1994 complaint where he was accused of excessive force by shoving someone, abusing his authority in a vehicle search, and cursing, though the details and resolution of that complaint are not publicly available.

“Caban is a living example of how extensive complaint histories, even substantiations for serious misconduct, don’t slow down careers in the NYPD,” said John Teufel, a lawyer and former CCRB investigator.

Many officers on the force for decades have multiple misconduct cases on their records, even those who rise to the top of the ranks. Former Police Commissioner Dermot Shea, for one, not only had abuse of authority charges substantiated against him, but was named in lawsuits against the department that resulted in the city shelling out over $100,000 to complainants.

Last year, the New York Post reported Caban was accused of cheating on his NYPD Sergeants’ exam in 1994, but was cleared for lack of evidence.

The mayor’s office declined to comment on Caban’s disciplinary history, pointing amNewYork Metro to an earlier prepared statement where Hizzoner praised him.

The NYPD did not return a request for comment.

Caban ascends to the top of the NYPD after the abrupt resignation of Sewell last month. Sewell hasn’t shed light on the reasons for her departure, but the New York Post reported she was frustrated with alleged micromanaging by City Hall. Sewell’s power was also often overshadowed by Deputy Mayor Phil Banks, who holds weekly press conferences on public safety and is a close ally of Mayor Adams.

The City reported last week that Sewell was personally asked by the mayor to not impose discipline on Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey, who was hit with misconduct charges for his role in voiding the arrest of a former underling who had allegedly menaced teenagers with a gun. Sewell went forward with disciplining Maddrey, who has opted to challenge the recommendation.

Sewell reportedly was stripped of her ability to approve promotions within the department after opting to discipline Maddrey, The City reported, at which point she realized the end of her tenure was near. It’s unclear whether Maddrey will still face discipline under Caban.