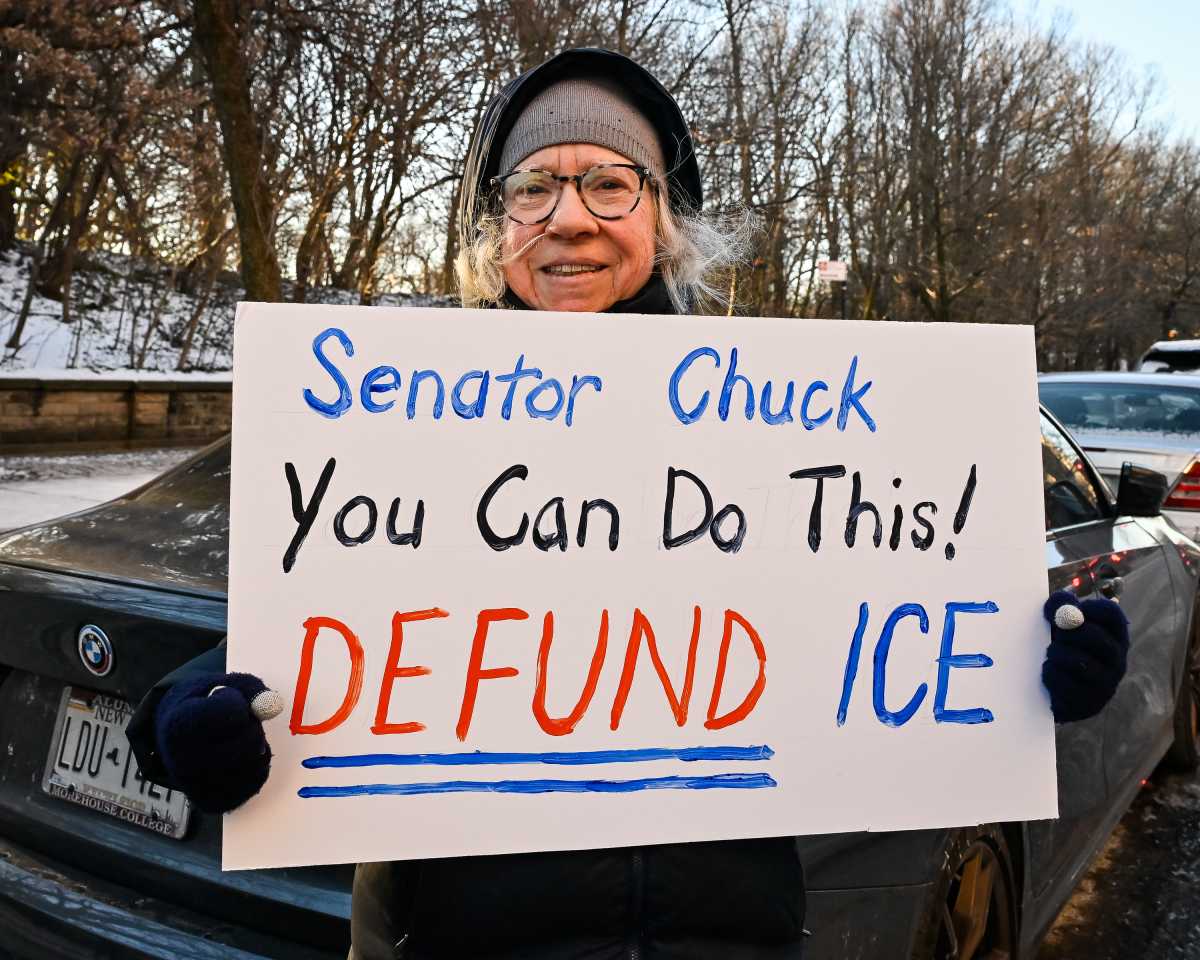

A cadre of anti-surveillance activists have joined forces with progressive lawmakers in Albany seeking to curtail the proliferation of “Big Brother” as government and corporate surveillance become an increasing part of everyday life.

The coalition plans to unveil on Monday a 10-point blueprint to make New York a “sanctuary state” against surveillance, starting with bills to ban “geofence warrants” and prohibit police from using fake social media accounts to ensnare suspects.

The campaign, which will be unveiled at a press conference outside the State Capitol in Albany, launches one day before Governor Kathy Hochul, newly inaugurated to a full four-year term, is scheduled to deliver her State of the State address.

The move comes as surveillance by government and corporate entities becomes ever more pervasive and entrenched in American life. Americans are now watched and listened to at nearly every moment of the day, through surveillance cameras on street corners; location trackers on their phones; smart speakers set to listening to every word they say in the home; advertisers tracking their web activity through cookies; and landlords seeking to require facial recognition for tenants to access their own homes.

Even as the tech world shed trillions in market capitalization last year, the surveillance tech sector continues to grow, with companies and government agencies shelling out billions for the latest spy gizmos.

And although public opinion still suggests wariness of surveillance, it’s becoming increasingly normalized. For instance, Hochul announced plans to install cameras on every subway car by 2025, comparing the policy to “Big Brother,” the totalitarian leader constantly watching the populace in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

“You think Big Brother’s watching you on the subways? You’re absolutely right,” Hochul said in September.

A spokesperson for the governor said Hochul “will review the [anti-surveillance] legislation if it passes both houses of the Legislature.”

Mayor Eric Adams has arguably gone further in favorable references to the dystopian classic, telling Politico last month that extensive camera and facial recognition surveillance should not scare New Yorkers, but in fact make them feel safe.

“It blows my mind how much we have not embraced technology, and part of that is because many of our electeds are afraid. Anything technology they think, ‘Oh it’s a boogeyman. It’s Big Brother watching you,'” Hizzoner told the outlet. “No, Big Brother is protecting you.”

Now, lawmakers and advocates hope to rein in tactics they consider highly troubling infringements on New Yorkers’ civil liberties, especially as authorities in conservative states seek to use surveillance tech to punish women getting abortions or teens seeking gender-affirming care.

Police in recent years have increasingly utilized “geofence” warrants to track suspects; if approved by a judge, cops can compel companies like Google to turn over data on who was using their phone in a given area at a certain time. Police can also execute “reverse keyword” warrants forcing Google to disclose who searched for given keywords at certain junctures.

The practices have been decried by privacy advocates who see the warrants as violating the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure.

Activists say it’s not a matter of theory, either: in Florida, a man was deemed a suspect in a burglary after riding his bike past the house and getting ensnared by a geofence warrant. In Arizona, a man was wrongfully accused of murder and jailed for six days after turning up on a geofence search.

The move to ban them in New York has the support of Google, and precedent was set against them last year when their use in catching a bank robber was declared unconstitutional by a Virginia judge. Even if the momentum appears on activists’ side, however, the ubiquity of the tech, and the fast-growing use of it by law enforcement, means action is needed with haste, they say.

“The ubiquity with which they’re being used is the reason why it’s so urgent,” said David Siffert, legal director at the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (STOP), an anti-surveillance group pushing the legislative package. “It’s affecting a lot more people. The police are getting enormous troves of data on enormous quantities of New Yorkers.”

Lawmakers supporting the package are also calling to prohibit law enforcement from using fake social media accounts to entrap suspects, and to ban the NYPD’s DNA database and government use of facial recognition software.

Another bill would ban law enforcement from “DNA phenotyping,” whereby DNA samples are used to create hypothetical mugshots of unknown suspects that are then distributed publicly, despite little evidence of their reliability. Yet another bill would ban the sharing of OMNY data with law enforcement, as advocates worry the new tap-to-pay system could make it easier to track people throughout the subway system.

Ultimately, supporters hope that the package can start turning the tide away from an increasingly new normal.

“Surveillance isn’t safety. These technologies have by and large not been used to keep people safe,” said Siffert. “They’ve been used to track undocumented people, they’ve been used to track Muslims, they’ve been used to keep communities of color under watch. A lot of this technology is inherently biased, facial recognition technology is substantially more inaccurate for people of color than it is for white people…These are ongoing problems that are actually affecting real people, they’re not just theoretical problems.”