BY ALEXANDRA JAFFE

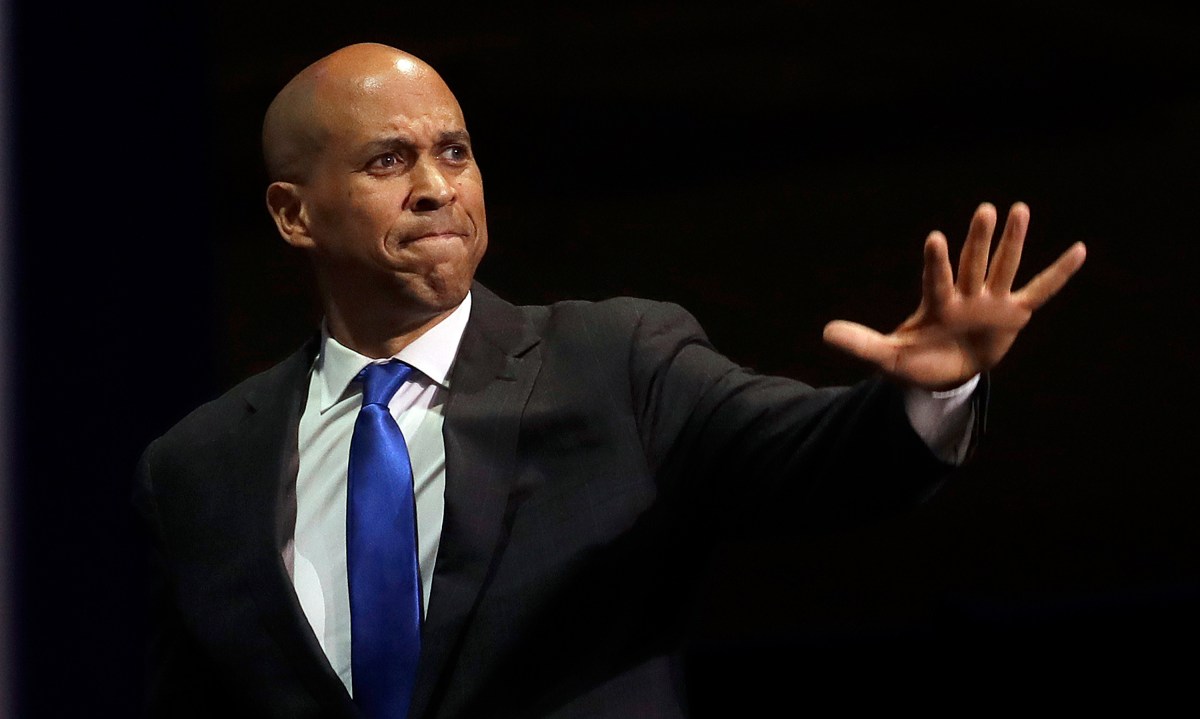

Democrat Cory Booker dropped out of the presidential race Monday, ending a campaign whose message of unity and love failed to resonate in a political era marked by chaos and anxiety.

His departure now leaves a field that was once the most diverse in history with just one remaining African American candidate, former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, who is struggling to register in the polls amid a late entry into the race.

Since launching his campaign last February, Booker, a U.S. senator from New Jersey, struggled to raise the type of money required to support a White House bid. He was at the back of the pack in most surveys and failed to meet the polling requirements needed to participate in Tuesday’s debate. Booker also missed last month’s debate and exits the race polling in low single digits in the early primary states and nationwide.

In an email to supporters, Booker said that he “got into this race to win” and that his failure to make the debates prevented him from raising raise the money required for victory.

“Our campaign has reached the point where we need more money to scale up and continue building a campaign that can win — money we don’t have, and money that is harder to raise because I won’t be on the next debate stage and because the urgent business of impeachment will rightly be keeping me in Washington,” he said.

For African Americans, Booker’s exit is more meaningful than just being one less option to consider.

“It means that we don’t count,” said Helen Moore, a member of the Detroit-based Keep the Vote-No Takeover grassroots organization. “Now, we can’t look forward to any black candidate being considered from now until it’s time to vote. They are completely out of the picture.”

Booker had warned that the looming impeachment trial of President Donald Trump would deal a “big, big blow” to his campaign by pulling him away from Iowa in the final weeks before the Feb. 3 Iowa caucuses. He hinted at the challenges facing his campaign last week in an interview on The Associated Press’ “Ground Game” podcast.

“If we can’t raise more money in this final stretch, we won’t be able to do the things that other campaigns with more money can do to show presence,” he said.

In his email to supporters, Booker pledged to do “everything in my power to elect the eventual Democratic nominee for president,” though his campaign says he has no immediate plans to endorse a candidate in the primary.

It’s a humbling finish for someone who was once lauded by Oprah Winfrey as the “rock star mayor” who helped lead the renewal of Newark, New Jersey. During his seven years in City Hall, Booker was known for his headline-grabbing feats of local do-goodery, including running into a burning building to save a woman, and his early fluency with social media, which brought him 1.4 million followers on Twitter when the platform was little used in politics. His rhetorical skills and Ivy League background often brought comparisons to President Barack Obama, and he’d been discussed as a potential presidential contender since his arrival in the Senate in 2013.

Now, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren has mastered the art of the selfie on social media. Another former mayor, Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, is seen as the freshest face in the field. Former Vice President Joe Biden has built a strong base of support with black voters. And Booker’s message of hope and love seemed to fall flat during an era characterized perhaps most strongly by Democratic fury over the actions of the Trump administration.

An early focus on building out a strong and seasoned campaign operation in Iowa and South Carolina may have hampered his campaign in the long run, as the resources he spent early on staff there left him working with a tight budget in the later stages of the primary, when many of his opponents were going on air with television ads. That meant that even later in the campaign, after he had collected some of the top endorsements in Iowa and visited South Carolina almost more than any other candidate, a significant portion of the electorate in both states either said they were unfamiliar with his campaign or viewed him unfavorably.

On the stump, Booker emphasized his Midwestern connections — often referencing the nearly 80 family members he has still living in Iowa when he campaigned there — and delivered an exhortation to voters to use “radical love” to overcome what he considered Trump’s hate. But he rarely drew a contrast with his opponents on the trail, even when asked directly, and even some of Booker’s supporters worried his message on Trump wasn’t sharp enough to go up against a Republican president known for dragging his opponents into the mud.

Booker struggled to land on a message that would resonate with voters. He’s long been seen as a progressive Democrat in the Senate, pushing for criminal justice reform and marijuana legalization. And on the campaign trail, he proposed establishing a $1,000 savings account for every child born in the U.S. to help close the racial wealth gap.

He was among the first candidates to release a gun control plan, and at the time it was the most ambitious in the field, as it included a gun licensing program that would have been seen as political suicide just a decade before. He also released an early criminal justice reform plan that focused heavily on addressing sentencing disparities for drug crimes.

But he also sought to frame himself as an uplifting, unifying figure who emphasized his bipartisan work record. That didn’t land in a Democratic primary that has often rewarded candidates who promised voters they were tough-minded fighters who could take on Trump.

Booker’s seat is up for a vote this year, and he will run for reelection to the Senate. A handful of candidates has launched campaigns for the seat, but Booker is expected to have an easy path to reelection.

Booker’s exit from the presidential race further narrows the once two dozen-strong field, which now stands at 12 candidates.