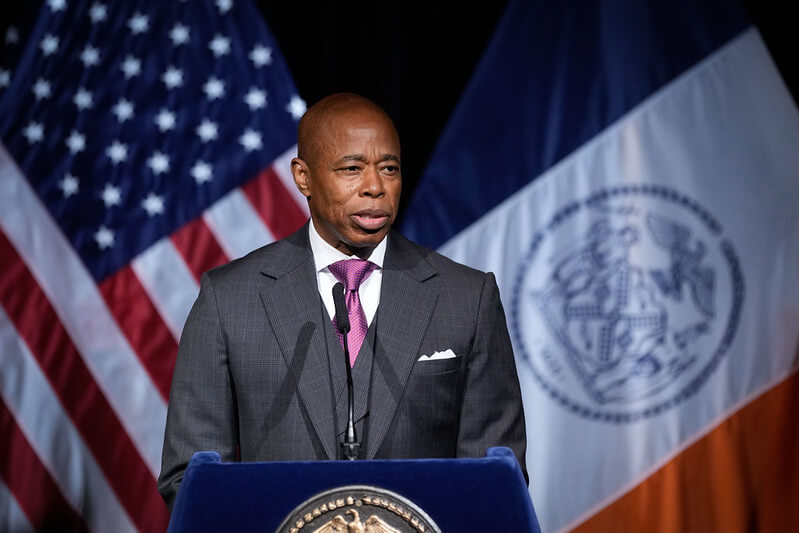

Mayor Eric Adams is pitching a new plan to address New York City’s dire housing crisis — aiming to invest in new mixed-income development in wealthier neighborhoods where affordable housing is particularly scarce.

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s (HPD) new “Mixed-Income Market Initiative” (MIMI) plan would leverage public dollars for the development of housing that mixes both market-rate and affordable units, a departure from HPD’s typical milieu of creating purely affordable housing.

Officials hope the mixed-income plan can lead to a greater number of units being built overall, including both income-restricted and market-rate dwellings, and ease pressure on the city’s housing market. They also contend subsidies for market-rate development would yield bigger returns due to their higher rents, allowing for more low-income development overall.

The MIMI plan, first reported Tuesday by the New York Times, is part of the administration’s effort to reach the mayor’s “moonshot” goal of 500,000 new homes over the next decade.

“Solving the housing crisis depends on new solutions and I’m proud of our HPD team who embraced the challenge to think outside the box,” said HPD Commissioner Adolfo Carrión Jr. “This bold new initiative goes beyond our limited resources and then steps outside conventional financing models to create affordable housing.”

Housing in New York is becoming increasingly unaffordable, to the point that the city’s population has shrunk 5% post-pandemic as low-and-middle-income residents seek more affordable living elsewhere.

More than a third of the city’s tenants are paying at least half of their income on rent, according to the Rent Guidelines Board, while the city’s homeless population is at a record high — with nearly 90,000 people residing in homeless shelters on a given day as migrants flood the city, and many more living on the street or couch-surfing.

Struggle to find solutions

Virtually everyone agrees the city is facing a severe housing crisis. What’s eluded New York’s political class is agreement on how to fix it.

Early this year, Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed what she called the “Housing Compact,” a plan to build about 800,000 new units of housing across the state largely by setting municipal growth targets and overriding local zoning in municipalities that failed to meet the mark. The plan met with furious opposition from suburban lawmakers, and the plan fell apart overall when state legislative leaders would not support the compact without new tenant protections and voucher programs for low-income New Yorkers. Hochul has since said she will not pursue the compact’s planks again.

In the meantime, the state’s 421-a tax break expired, eliminating a key program developers relied upon to finance affordable housing development even as many lawmakers and advocates derided it as a giveaway to wealthy real estate magnates. MIMI aims to pick up some of the slack that has been missing since 421-a’s expiration.

In the city, the mayor signed a bill this year that sets housing growth targets in every neighborhood across the five boroughs, and has also proposed sweeping zoning reforms to cut red tape that prevents dense housing development.

Under MIMI, at least 70% of a development’s units must be considered “affordable,” but the term itself has often been a source of controversy in the city over how it is calculated. With MIMI, income-restricted housing can be targeted to tenants making up to 120% of the “area median income (AMI);” this year, that means a family of four taking home nearly $170,000 in pay can qualify for income-restricted housing.

Nevertheless, MIMI specifies that a quarter of income-restricted units (about 17.5% of overall units) must be set aside for households making less than 50% of the AMI, or $70,600 for a family of four. Within the quarter, 15% of units must be set aside for formerly homeless New Yorkers.