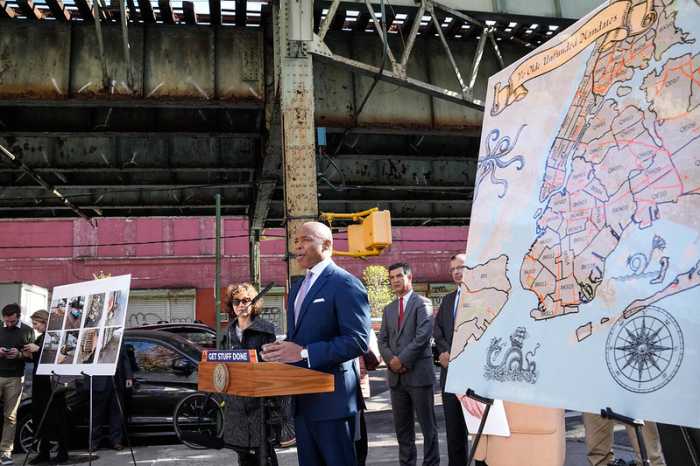

Three months after Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to ramp up involuntary commitments for the severely mentally ill, he rolled out what he billed as the “second phase” of his mental health strategy on Thursday, in the form of a three-pronged effort to tackle youth mental health, overdose deaths and severe mental illness.

The plan, titled “Care, Community, Action: A Mental Health Plan for New York City,” would put $22.8 million toward funding initiatives to tackle parts of the city’s ongoing mental health crisis that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

It includes launching of a telehealth program for high school students, rolling out a youth suicide prevention pilot program at city hospitals, adding more “overdose prevention centers” and expanding the number of “Clubhouse” spaces across the city — among other initiatives.

The mayor said his administration has come to a “deeper understanding” of the importance of addressing gaps in the city’s mental health care system as it continues to recover from the pandemic.

“As we recover and rebuild, we have come to a deeper understanding that we must focus on the brain as much as the body,” Adams said. “We must address the whole person, the whole system.”

“We realized that this mental health crisis started long before the pandemic and that we will have to change the way we approach mental health as a city, as a community,” he added. “That change begins now, with us.”

Adams said the plan was crafted over the past year using input from several city agencies across his administration.

“This plan is the result of an intensive interagency effort over the last year, one that drew on every part of our city government,” the mayor said. “From our healthcare experts to our first responders, and our educators, we looked for gaps in care and ways to get people mentally healthy and physically healthy.”

The overall $22.8 million in funding for the plan breaks down into $12 million for the youth telehealth program, $7 million over the next four years for expanding Clubhouse spaces and another 3.8 million for “single access sites” where individuals with mental illness can access services, according to a mayoral spokesperson. The mayor said he’ll also seek additional dollars from Albany and Washington.

The first area of the plan focuses on youth and family mental health, the mayor said, due to the trauma and isolation young people experienced throughout COVID. Adams pointed to the fact that 9.2% of New York City high school students reported attempting suicide in 2021 to underscore the urgency of the issue.

That’s why the city is creating the telehealth program for high school-aged teens, which will be the largest of its kind in the country, according to city Health Commissioner Dr. Aswin Vasan.

“With technology that they’re used to, teens can connect with a specialist fast, right when they need it, not after the problem has spun out of control,” Vasan said.

The suicide prevention pilot, Vasan said, is a hospital-based interruption program, where peer counselors and social workers can be with youth who’ve attempted suicide during the first 90 days after the attempt, when children are most likely to try again.

Vasan said the Department of Health will also be doing a survey in the coming months to get a better understanding of the youth mental health crisis across the city. Plus, he said, they’re going to work to better understand the negative effects of social media on the city’s young people.

“Exploring pathways to reduce their negative exposure, the same way the city has done with other toxins like tobacco or air pollution,” Vasan said.

When it comes to tackling overdoses, the mayor stated an ambitious goal of reducing overdose deaths by 15% over the next two years. One way the plan intends to do that is by opening five new overdose prevention centers — sites where people can use drugs under the supervision of medical professionals — by 2025.

Under the plan, the city also aims to expand 14 of its 15 syringe service providers, which provide services to drug users, into so-called “Harm Reduction Hubs.” In addition to addiction services, the hubs will provide a resting place, medical and mental health services.

“The goal is to reduce overdose deaths by 15% by 2025,” Vasan said. “We must have more overdose prevention centers in order to reach that goal. And I think what’s important for readers to understand and the public to understand is that overdose prevention centers are also built around all of the other supportive services that are input into those sites.”

The plan seeks to tackle severe mental illness partially by building out the capacity of clubhouses, spaces where those with severe mental illness can receive services whether or not they’re insured. Those spaces provide severely mentally ill individuals with social interaction and meals as well as educational and employment services.

The mayor also proposed building an additional 8,000 units of supportive housing.

The ultimate goal of all these measures, Vasan said, is to make it so people suffering from mental illness or addiction never get to the point where the city has to involuntarily commit them to a hospital for evaluation.

“The goal of this plan is to ensure that as few people as possible ever end up in the need for that kind of care,” he said. “There are 250,000 people living with serious mental illness in our city, 40% of those people are not in treatment — 96,000 people. All of those people are at risk, if we don’t surround them with care, of ending up in crisis. And the goal of this plan is making that number is as small as possible.”