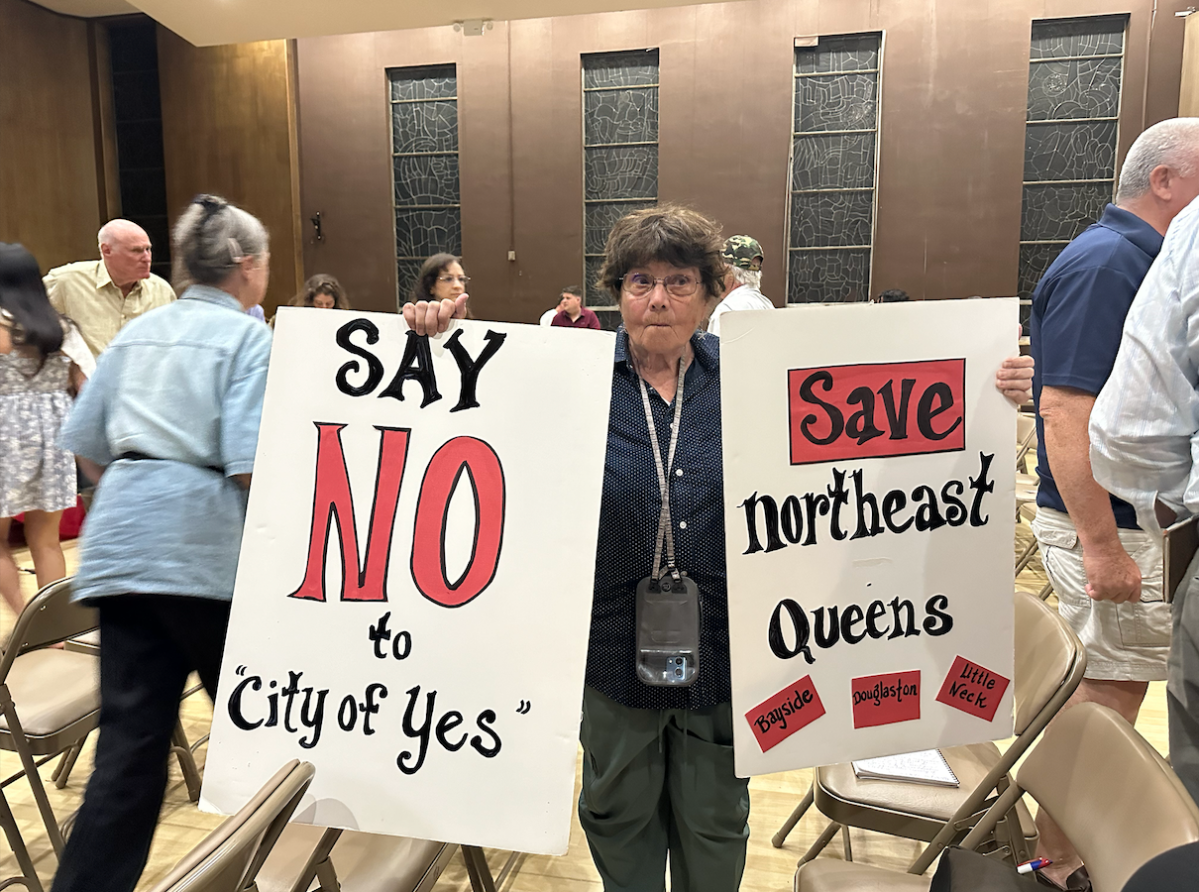

Mayor Eric Adams has proposed three sprawling amendments to the city’s zoning code that he says would transform the Big Apple from a mess of red tape to a “City of Yes.”

The amendments are aimed at making it easier for the public to do business in the city, along with spurring housing development and easing the transition to clean energy. The proposals range from eliminating restrictions on rooftop solar panels and electric vehicle charging infrastructure, to removing antiquated dancing restrictions, to limiting existing parking requirements for new residential development.

“The City of Yes proposals are designed to speed up our recovery, and to create a healthier and more affordable city, so we are excited to begin the public conversation,” said Dan Garodnick, chair of the City Planning Commission, in a statement this month. “We are starting this process early, while we are still drafting the plan, in order to ensure robust community engagement. We hope people turn out to share their views.”

The first public information session on the wide-ranging proposals is set to take place virtually on Monday night, Oct. 17, at 7 pm.

The proposals are only in their infancy and have not yet been fully fleshed out. The contours align with the mayor’s campaign pledge to cut red tape, though they will still, of course, have to go through the city’s red tape-laden public engagement process before approval and implementation.

New York City’s current zoning resolution dates back to 1961, and has been amended innumerable times since then, its advanced age means the foundation of the document does not address present-day challenges of city planning, such as the impact of the climate crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and increasingly unaffordable housing. The 1961 resolution effectively limited the amount and density of housing that could be built in most of the city as policy wonks of the time forecasted permanent explosive growth of the suburbs and automobile commuting.

Previous efforts to replace the aging code with a new one have failed, and so instead, the 1961 resolution has been amended over and over mainly by rezoning certain areas, and occasionally with citywide efforts like 2016’s Zoning for Quality and Affordability, which shepherded the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing program.

“I think there’s maybe one or two people living with a real understanding of the zoning cabal,” said Marcel Negret, a senior planner at the Regional Plan Association, which is optimistic about the administration’s zoning reform efforts but awaiting further details. “All these generations of tweaking and adding to it, it’s turning into almost a monster.”

The administration says that the relaxation of certain residential zoning rules would allow for greater proliferation of housing and, in turn, more affordable housing. The proposal calls for axing red tape around converting old office space into residential units, and would allow any development that includes affordable housing to be built larger than market-rate buildings, a privilege that currently only applies to senior affordable housing.

Most notably, the housing proposal calls for reducing parking requirements for new residential developments across the city, which have long been criticized as hindering housing development and effectively encouraging car ownership in dense pockets of the city.

To meet another 21st-century need, namely reducing and eliminating carbon emissions, the proposal would make changes to the zoning code integral for New York to meet its goals, and mandates, to reduce carbon emissions by 80% come 2050.

The changes would put the kibosh of zoning rules that stand in the way of buildings meeting new energy efficiency standards, and would ease existing limits on installation of rooftop solar panels and electric vehicle charging infrastructure, the latter intended to facilitate both electric cars and micromobility like scooters and e-bikes.

As for commercial red tape, the most eye-catching proposal would cause all restrictions on dancing to sashay on out of the zoning code. The city in 2017 repealed its infamous 1926 Cabaret Law, which had banned dancing in city bars and clubs without a cabaret license and was enforced in a discriminatory manner against people of color and LGBTQ+ New Yorkers. but dancing restrictions live on in the zoning code and ipso facto still prohibit dancing in areas of the city not zoned for it.

Adams, well-known for his proclivities towards nightlife, wants New Yorkers young and old to “get up and dance at a bar” anywhere in the city knowing they are not breaking any laws.

The reforms aim also to liberalize zoning districts restricted to only certain commercial activity, and enable more efficient “adaptive reuse” by loosening rules requiring new business tenants to renovate their spaces if former tenants conducted substantially different commerce.