The Adams administration has proposed zoning changes allowing casinos to be sited in wide swaths of the city with few limits on their footprint, amid a furious bidding war for one of three rare licenses for a downstate New York casino.

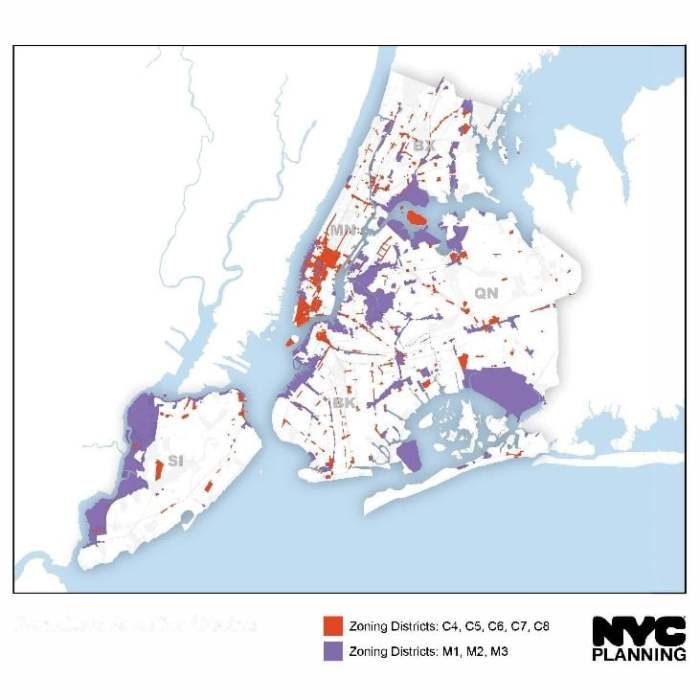

The zoning proposal would allow casinos to be sited within any manufacturing district and all but the lowest-density commercial areas, and includes no restrictions on their size. The proposal would also allow developers to include related uses in the footprint of a gaming hall, like restaurants, hotels, bars, and performing arts venues.

Administration officials say the sweeping zoning changes are necessary to ensure smooth regulatory sailing for whoever wins a highly coveted license to operate a casino in New York’s downstate region, whose untapped potential for the gambling market has long occupied the dreams of the industry. Specifically, officials believe the zoning amendments will make the city a more competitive option for the licenses compared to its surrounding environs, since casinos are not currently a permissible use in the city’s zoning code.

“As the state considers proposals for casinos downstate, it’s important that we create a level playing field for applicants within New York City so they can compete for this opportunity,” said Dan Garodnick, head of the Department of City Planning and the City Planning Commission. “This text amendment would avoid duplicating the state’s rigorous licensing process…while setting up a rational framework for consideration within our zoning.”

Despite that, most of the publicized casino bids seek to build within the city, gunning for easy access to gambling by the city’s 8.8 million residents. Real estate and gaming giants have proposed building casinos at Times Square, Hudson Yards, the United Nations, Coney Island, Citi Field, and the former Trump Links golf course at Ferry Point Park, to name a few. The only major bid for a brand new casino outside the city is at the Nassau Coliseum site on Long Island.

Industry insiders consider the region’s two existing “racinos,” at Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens and Empire City Casino in Yonkers, to have a leg up in the competition, since they already have casino footprints at racetracks with video slot machines, but not table games like poker, blackjack, and craps.

That has only made the competition for the remaining license more fierce, as bidders do everything from sponsoring local sports leagues to launching free shuttle bus service between casino sites and mass transit — to say nothing of their expenditures on lobbying and campaign contributions.

The overarching zoning proposal must snake through the city’s land use review process, getting advisory approval from local community boards where bids are submitted, as well as the Borough Presidents and Borough Boards, before statutory nods from the City Planning Commission, City Council, and Mayor. But approval of the zoning amendment would mean whichever projects are chosen for the licenses would not need to go through that same process, which is notoriously lengthy, complex, and expensive.

Before being selected by the state Gaming Commission, a proposal must get two-thirds approval from a “Community Advisory Committee” made up of representatives of the governor, mayor, and the local state Assembly Member, state Senator, Borough President, and City Council Member. Bids that secure such approval in their communities can then be considered for a license by the Gaming Commission.

The community input component could spell doom for some bids with considerable local opposition, like the one in Coney Island. It’s unclear when the Gaming Commission will proclaim its final decision.

The zoning change would only apply to the three licenses currently being deliberated, and would not be in effect for any future bids, according to documents filed online last week.

Some civic gurus found the bare-bones proposal to be puzzling, placing few restrictions on a massive gambling and entertainment complex when the smallest changes to one’s property can get people caught up in vast amounts of red tape.

“This is very unusual for New York City not to be very specific,” said Layla Law-Gisiko, the land use chair at Manhattan Community Board 5, which includes bid locations at Times Square and atop Saks Fifth Avenue. “It says nothing.”

Law-Gisiko was recently at the center of a fight to limit the length of Madison Square Garden’s special operating permit, which ultimately was renewed for five years, less than the Adams administration and the Garden wanted. She contrasted the casino proposal with the hyper-specificity of the “arena text amendment,” which went into painful detail on everything from the Garden’s loading zones and transportation management to planters and seating it would need to build outside Penn Station.

Unlike the MSG amendment, the casino proposal is curiously scant on details, and includes provisions that seemingly stand in contradiction with the city’s own zoning code. For instance, since 2021 all new hotel developments have required a “special permit” from the city, ostensibly to reduce “adverse effects” on local communities, but a casino developer would be able to build a hotel as an accessory to their gaming facility, without obtaining a separate permit.

“It is unusual that the city would not shape the physical environment of an establishment as large as a casino,” said Law-Gisiko. “And we hope that the text will be much strengthened through the review process.”

Read more: Manhattan Rental Market Attracts Generation Z Tenants