Sam Chaney, one of the city’s rent freeze specialists, rapped on a door on the second floor of a Flatbush apartment building recently.

George Chambers, a 41-year-old construction worker, cracked it open and peered at Chaney’s city badge while he explained to the resident that the government has tasked him with helping senior citizens apply to freeze their rent.

Chaney asked a series of questions he said would help him gauge whether Chambers’ family qualifies for the city’s so-called Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE).

Yes, Chambers said, his father was over 62, had signed the lease and was part of a household that spent more than one-third of its income on rent. Chaney said he believed the apartment was rent-regulated, as required under the program.

“The application is deceptively simple,” Chaney said, handing Chambers a single slip of paper through his doorway. “What’s really doing the work on this application is the documentation.”

On the back of an envelope, Chaney wrote a checklist with the documents the family would need to copy and submit. He handed it to Chambers and said he would be in touch.

“I would be grateful,” Chambers said, when asked about the prospect of avoiding future rent increases.

For the past two-and-a-half weeks, Chaney and nine others have been going door-to-door, working off a list of names and addresses of the tens of thousands of people the city believes could benefit from the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption. Recipients do not have to pay rent increases. The city compensates their landlords for the lost revenue by applying a credit to their property tax bills.

New Yorkers have long struggled to enroll in the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption program and a similar initiative aiding the disabled: the Disability Rent Increase Exemption (DRIE). Promotional materials have not historically broken through language barriers or had a wide reach, according to a 2014 city report. At that time, the city esimated that 69,000 eligible households were not benefitting from SCRIE and nearly 25,000 qualified families were not receiving DRIE.

Applicants do not always realize they must attach copies of documents. And many have a hard time finding a copy of their lease that contains signatures from them and their landlord, city officials said. Some New Yorkers find it difficult to get copies of documents showing their household’s income over the past two years, which can require gathering income tax returns, W2s, Social Security or public assistance benefit letters, pension statements and more.

In 2016, the city settled a lawsuit and agreed to compensate 10 New Yorkers who said they were unfairly removed from these programs after their spouses or parents died. Their lawyers argued the city had done a poor job notifying SCRIE and DRIE recipients about a rule change.

The city has undertaken various efforts to guide more eligible families through the application process. Since 2014, some 18,000 new households have joined SCRIE; 3,500, DRIE. With help from the new outreach team, the city aims to add 10,000 more beneficiaries this year to SCRIE, DRIE and similar initiatives for low-income homeowners, according to Regina Schwartz, director of the city’s Public Engagement Unit.

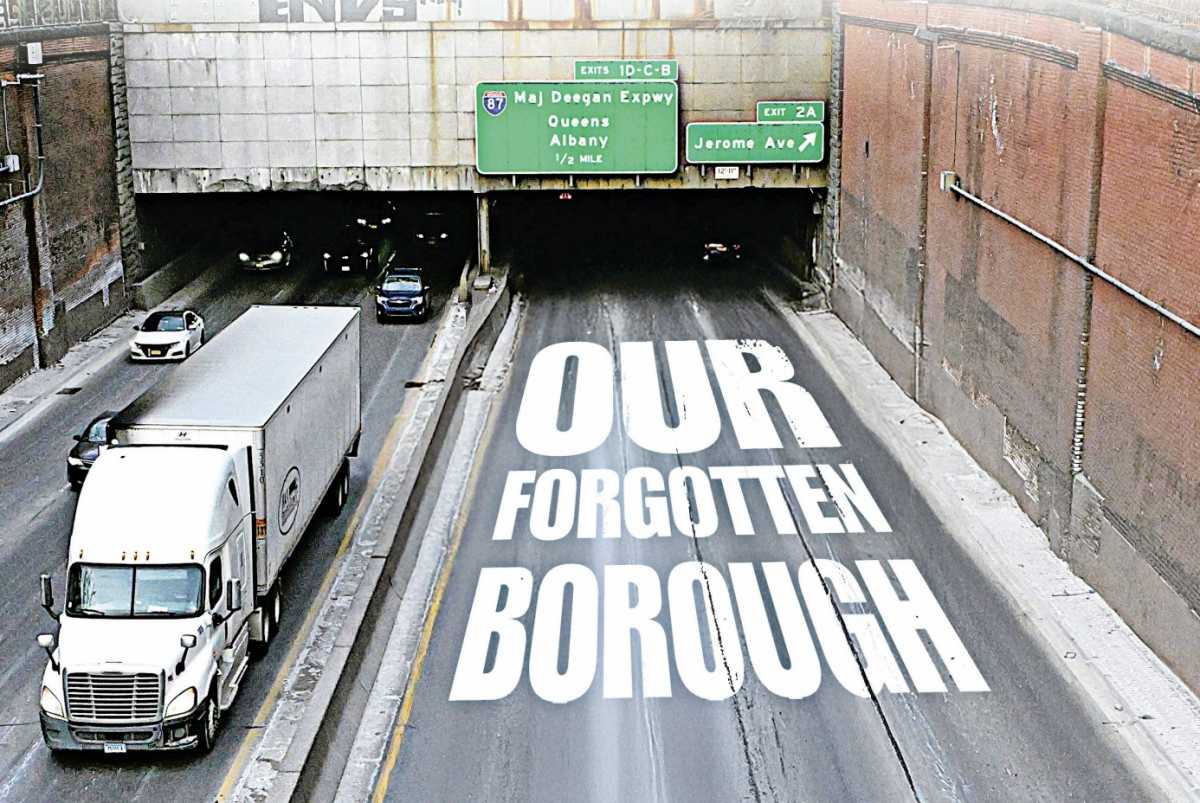

Schwartz said the city’s door-to-door teams are targeting areas where demographic and housing research shows many eligible for the exemptions are not receiving them, including Washington Heights, Harlem, East Harlem, the Lower East Side, Midwood and Flatbush. Over the next six months, the teams will begin working in a dozen other neighborhoods across Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx.

“We are proactively managing folks through that process in a way the city has really never done before,” Schwartz said.

On the ground in Brooklyn, this door-to-door outreach sometimes sends Chaney knocking without receiving a response. When that happens, he leaves behind a flyer explaining the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption and his business card.

Even when people do answer, Chaney sometimes has to convince housemates to pass along his message.

But when he arrived at a scheduled follow-up appointment with Marie Louis, 66, she was waiting for him with a stack of papers.

Chaney flipped through her completed application and realized she was missing a 1099 form showing how much she received in Social Security payments.

Louis said her social worker had sent in her original 1099 when she unsuccessfully applied for the rent freeze program in 2016. She struggled to get another 1099 at the local Social Security office.

“Requesting a 1099 is not easy to do when you do it on the phone, but I’ve done it before,” Chaney said, while agreeing to help Louis call the Social Security Administration later that day. “I can make it simple.”