For the 10th consecutive year, the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) did not elect Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, ending their candidacy on the ballot.

It was a win for the minority within the 394 so-called gatekeepers of baseball history who voted this year, maintaining that the Hall of Fame should not honor those linked to performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs).

Both Bonds and Clemens are two of the most notorious names linked to the height of baseball’s steroid scandal from 1995-2004, casting doubt upon their eligibility for enshrinement despite being two of the very best players the game has ever seen.

Bonds holds baseball’s all-time home run record both for a career (762) and in a single season (73) along with walks (2,558) and MVP awards won (7). He was a five-tool player for the majority of his career. By the end of the 1998 season — which was the final season before his steroid usage allegedly began — he was the only player in MLB history with 400 home runs and 400 stolen bases with an on-base percentage of over .400. No one in the game has done that since, either.

Clemens was a fire-balling right-hander that had already accrued three Cy Young Awards and an American League MVP by the 1991 season. But after a down spell that ended his time in Boston, Clemens’ game experienced a resurgence in 1997 — and it only got better. Between the ages 34 and 42, Clemens won four more Cy Young Awards, posted a 3.22 ERA, and went 149-61.

His seven Cy Youngs are the most won by any pitcher while his 354 wins rank ninth all-time and 4,672 strikeouts are third-best in baseball history.

Throughout their first nine years of eligibility on the BBWAA ballot, their percentages slowly rose ever closer to that magic 75% mark. But entering Year No. 10, there was an inkling that maybe, finally, the writers were willing to change their ways and unlock the doors in Cooperstown for two resumes that would undoubtedly be first-ballot entries if not for PED usage.

Their numbers did go up, but it was not enough. Bonds jumped from 61.8% last year to 66% while Clemens hopped from 61.6% to 65.2% and the Hall’s entryway remained blocked for steroid users.

Except that notion quickly evaporated within seconds.

The perch that the writers stood upon for more than a decade came crumbling down when David Ortiz — the long-time Boston Red Sox slugging designated hitter — was elected into the Hall on his very first year of eligibility, receiving 77.9% of the vote.

Ortiz was one of more than 100 players who tested positive for banned substances in 2003 as Major League Baseball began working on its program to test players for PEDs. The 541-home-run-hitter has denied taking such substances, citing that he never failed another drug test in the remaining 13 years of his career, which were the seasons that put him on a Hall-of-Fame trajectory.

Such a link didn’t hurt his chances, though. Meanwhile, it derailed Bonds and Clemens.

Bonds never failed an MLB administered drug test after testing became mandatory in 2003 — hitting 45 home runs both in 2003 and 2004. He did, however, test positive in 2000 — which was revealed during the famed BALCO trial.

A report in 2007 alleged that he failed a test in 2006, but for amphetamines, in the drugs’ first year on MLB’s banned substances list. Amphetamines, or greenies, were one of the most commonly used drugs throughout baseball for decades. Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, and Willie Mays were three of the most prominent former ballplayers who admitted to using them. All three have plaques proudly displayed inside Cooperstown.

Clemens never failed a drug test, either.

“Not having them join me at this time is something that is hard for me to believe to be honest with you,” Ortiz admitted. “Those guys did it all.”

After Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens’ snub, welcome to the latest chapter of hypocrisy in Major League Baseball.

Baseball over the years has been built on exactly that.

A game labeled as America’s Pastime only allowed white ballplayers to partake at its highest level from 1887-1946.

A game that’s advertised as one for the people is mired in ceaseless negotiations between billionaire owners and millionaire players about a fistful of dollars.

A game that was once plagued by gambling in its early years, headlined by the Chicago White Sox’s throwing of the 1919 World Series, was rocked to its core in 1989 when the league’s all-time hits leader, Pete Rose, was banned for life for betting on games. In 2018, BetMGM became MLB’s first gaming partner. Last season, the Washington Nationals opened up a sportsbook just outside their stadium.

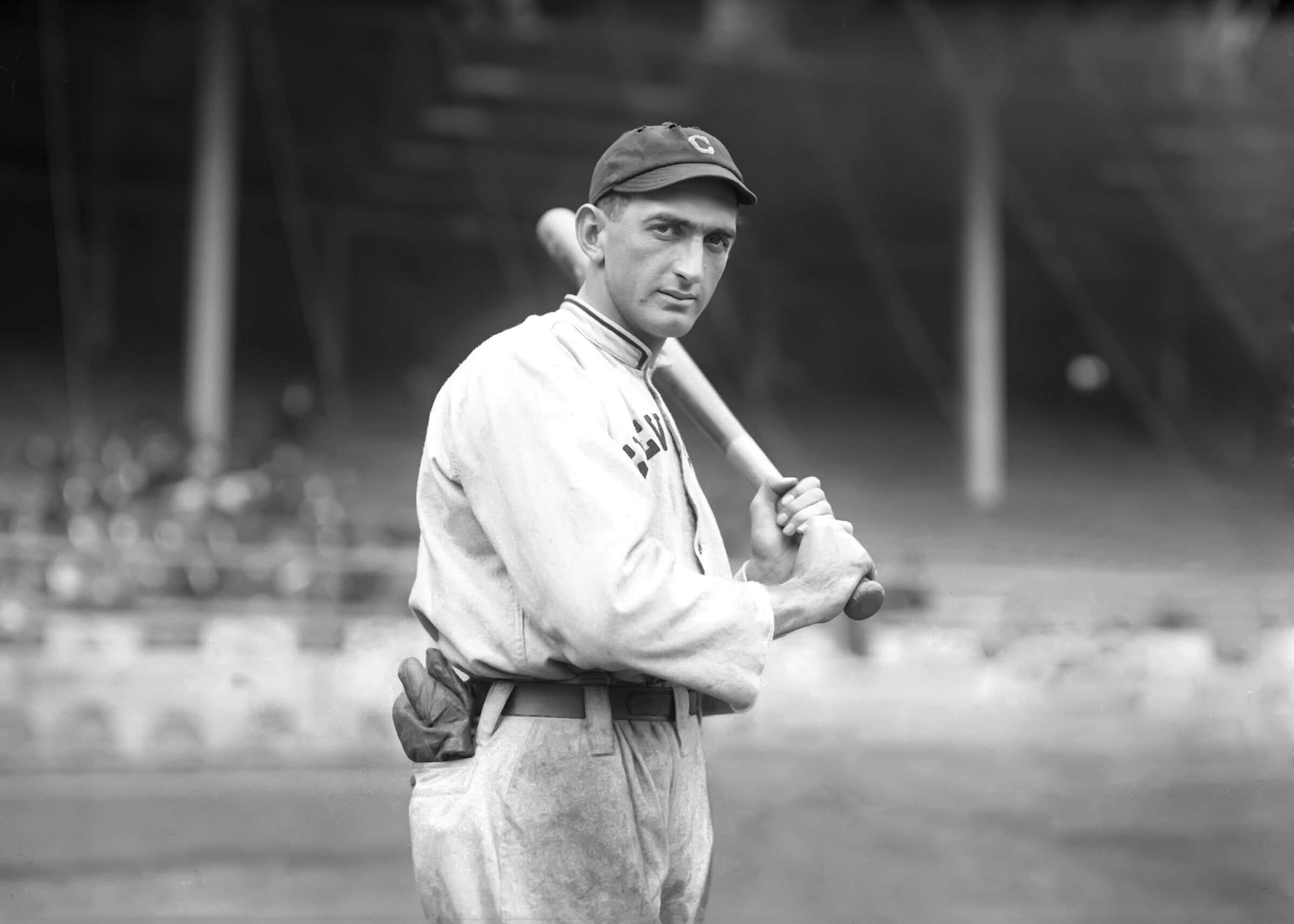

Rose has continuously petitioned for his lifetime ban to be lifted, to no avail. “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, the star of those 1919 White Sox who batted .356 over a 13-year career (fourth all-time) still hasn’t had his name cleared despite there being no legitimate evidence that he accepted money or helped throw that eight-game World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. He batted .375 with one home run and six RBI in that series. His 12 base hits that series was a record that wasn’t broken until 1964.

Both should be in the Hall of Fame.

A game that is as American as democracy picks and chooses which forms of cheating it will tolerate.

One of the most famous and celebrated plays in baseball history, Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” that won the 1951 NL pennant for the New York Giants over the Brooklyn Dodgers and can be seen at the Hall of Fame is still mired in a sign-stealing scandal.

Giants players told the Wall Street journal in 2006 that a telescope was used in the team’s clubhouse behind center field at the Polo Grounds to steal the signs of opposing catchers. Those signs were relayed to a buzzer connected to the clubhouse to telephones in the Giants’ dugout and bullpen. One buzz for a fastball, two for anything else.

Sound familiar?

The 2017 world champion Houston Astros was found guilty of stealing signs using cameras that relayed images of the opposing team’s signals to a tv monitor just inside the tunnel of the team’s dugout. Signs were then relayed using the banging of a trash can.

Alex Correa, Alex Bregman, and Jose Altuve are still enjoying successful playing careers. AJ Hinch was fired by the Astros but got another job managing the Detroit Tigers and Alex Cora — the former bench coach — took one year off from managing the Boston Red Sox.

Let’s see if this impacts the Hall-of-Fame candidacy of Carlos Beltran, who will be eligible next year and was the only player impacted by the findings of commissioner Rob Manfred.

Now, if we couple performance-enhancing drugs with a contentious relationship with the baseball writers — like Bonds and Clemens had — you have no shot at the Hall. But if the writers view you as a loveable folk hero with links to PEDs, regardless of how minor, you’re in.

Alex Rodriguez and his 696 home runs only received 34% of the vote this year — his first on the ballot. Whether that’s only because he outright admitted he used steroids or because he also had a hot-and-cold relationship with the media, that’s for you to decide.

The Hall of Fame is a museum that is supposed to tell the entire story of America’s Pastime. However, it now does not feature the game’s all-time home run leader, all-time hits leader, and all-time Cy Young Award winner leader.

How is that properly teaching us the history of the game?