Major League Baseball announced Wednesday morning that they have officially elevated the status of the Negro Leagues to that of a “Major League.”

“All of us who love baseball have long known that the Negro Leagues produced many of our game’s best players, innovations, and triumphs against a backdrop of injustice,” MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said. “We are now grateful to count the players of the Negro Leagues where they belong: as Major Leaguers within the official historical record.”

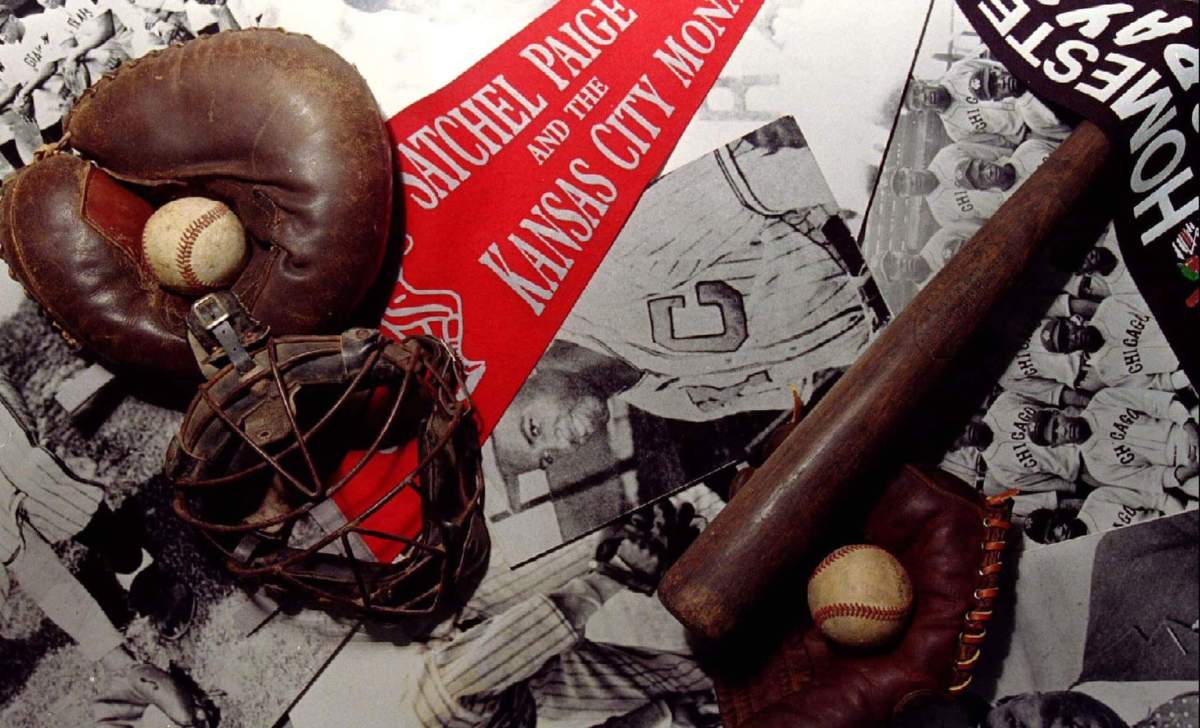

The announcement comes during the centennial celebration of the Negro Leagues, which was founded in 1920 as a top-tier organization for Black ballplayers to participate due to MLB’s “gentleman’s agreement” that barred people of color from playing.

Consisting of seven distinct leagues over a 28-year span, the Negro Leagues’ approximate 3,400 players will finally have their statistics and records officially included in MLB’s history books.

“The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is thrilled to see this well-deserved recognition of the Negro Leagues,” Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, said. “In the minds of baseball fans worldwide, this serves as historical validation for those who had been shunned from the Major Leagues and had the foresight and courage to create their own league that helped change the game and our country too.

“This acknowledgment is a meritorious nod to the courageous owners and players who helped build this exceptional enterprise and shines a welcomed spotlight on the immense talent that called the Negro Leagues home.”

While the likes of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx dominated MLB, the Negro Leagues featured talents that would have starred in the majors, including pitcher Satchel Paige, slugging catcher Josh Gibson, and the brilliant center fielder, Oscar Charleston.

In total, 84 players that are currently enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown played in the Negro Leagues. The league also provided starts for the likes of Jackie Robinson — who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers — long-time home-run king Hank Aaron, and the incomparable Willie Mays, deemed by many to be the greatest all-around ballplayer who ever lived.

“The perceived deficiencies of the Negro Leagues’ structure and scheduling were born of MLB’s exclusionary practices, and denying them Major League status has been a double penalty, much like that exacted of Hall of Fame candidates prior to Satchel Paige’s induction in 1971,” John Thorn, the official historian of MLB, said. “Granting MLB status to the Negro Leagues a century after their founding is profoundly gratifying.”