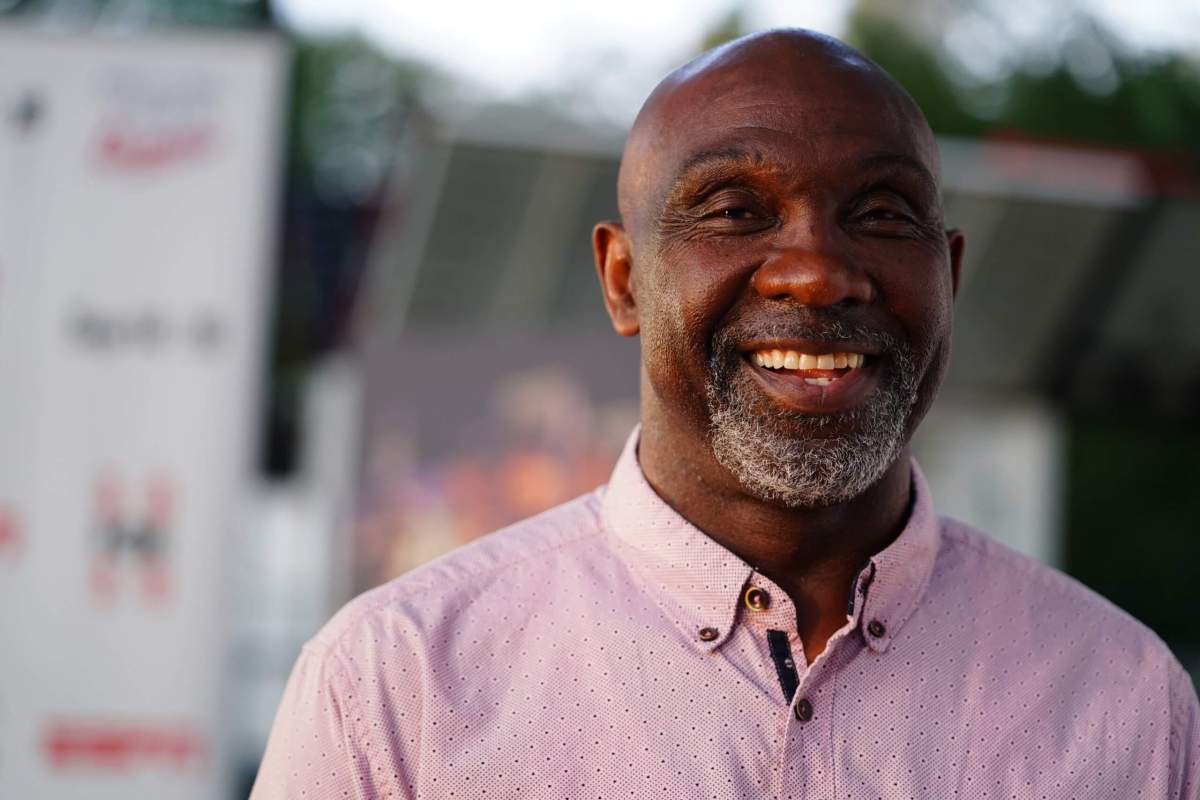

Mookie Wilson will never get tired of talking about that famous little roller up along the first base side that went behind the bag and got through Buckner to win Game 6 of the 1986 World Series — even if he isn’t in love with that word “roller.”

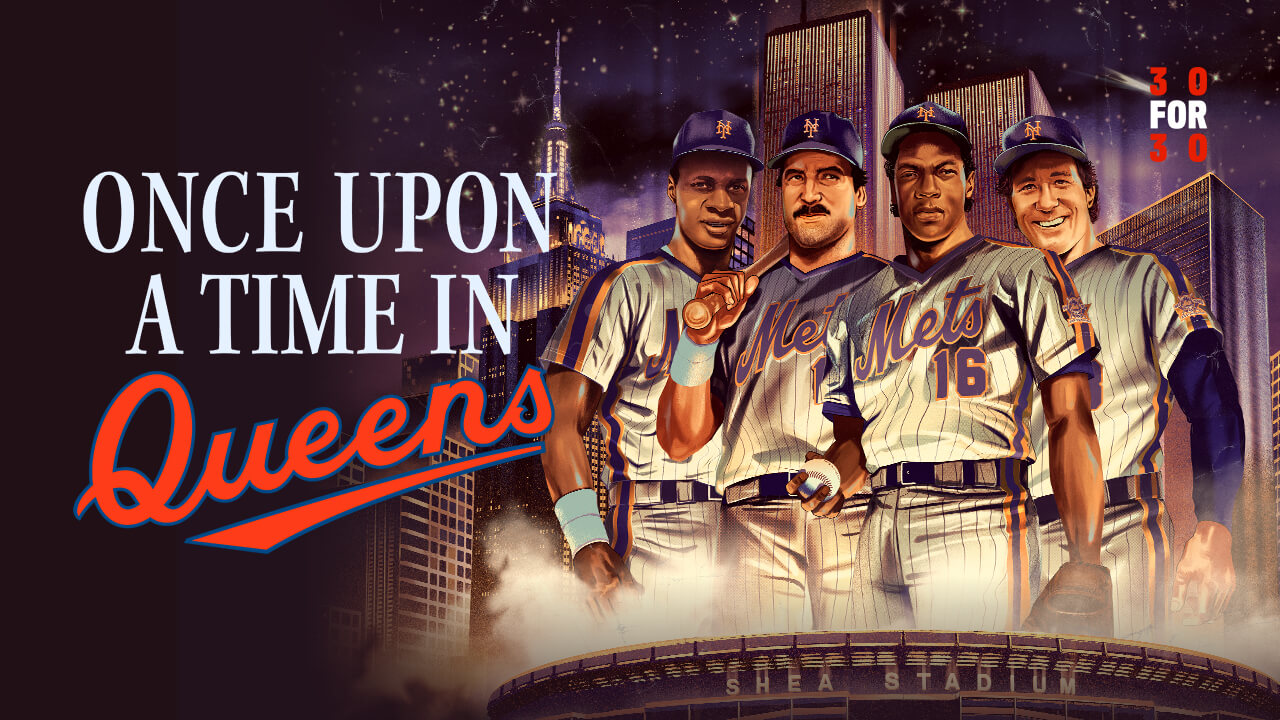

“You don’t have to call it a roller man, come on,” he jokingly told me as we discussed that magical season for the New York Mets ahead of the premiere of ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentary, Once Upon A Time In Queens. “I hit the ball pretty good.”

But at the time 35 years ago when the Mets rallied from two runs down in the 10th inning to put the tying and winning runs on base with two outs in the face of elimination, Wilson wasn’t so eager.

“I’m not going to lie to you, I would’ve rather had somebody else be up there,” Wilson admitted. “I had been in New York a long time and I know that when you fail in New York, sometimes there’s no coming back from it.

“I’m not going to say that I went up there and had it all covered because I didn’t.”

Of course, Wilson’s at-bat on the night of Oct. 25, 1986, at Shea Stadium will forever be stitched into the fabric of baseball history as one of the most iconic plays the game has ever seen — a bouncing grounder that got through the legs of Boston Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner to score Ray Knight to win the game and force Game 7.

But the journey there was a long one for Wilson; longer than anyone else that was wearing a Mets uniform on that night.

The Rebuild

Wilson was one of the only members of the Mets’ 1986 roster that had been with the team at the beginning of the decade.

He made his MLB debut in 1980 for a Mets team that hadn’t finished higher than third place in the National League East since they won the National League pennant in 1973.

They were seemingly going nowhere, winning fewer than 70 games in each of Wilson’s first four seasons.

“Being there at the beginning, when I first got there I’ll be honest with you, I didn’t think there was any hope for that team,” Wilson said, admitting that he had more fun in the minors. “I thought that team was a lost cause. It was bad then. It’s not so much that there were bad players, we just had a lot of players who acted like they didn’t want to be there.

“Then all of a sudden, you started seeing glimpses of hope. We were still losing, but there was some energy, there was some excitement, there was some potential.”

That was sparked by the acquisition of Keith Hernandez from the St. Louis Cardinals and the call-up of their highly-touted top prospect, Darryl Strawberry in 1983. Doc Gooden made it to the show in 1984 and electrified the league and suddenly, the Mets were contenders, winning 90 games that season.

“It changed quickly,” Wilson said. “From ’83 to ’84 it was a totally different ballclub. You’d never think that was the same ballclub.”

Gary Carter was brought on in 1985, so were Howard Johnson, Ray Knight, and Lenny Dykstra. They won 98 games, finishing second to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Early Worries

Then came the spring of 1986 and manager Davey Johnson’s bold proclamation to reporters that the Mets were going to “dominate” that season.

“It was shocking that the manager would say it. That was surprising,” Wilson said. “We had some guys on that team you’d expect to say it, guys like [Strawberry] or Wally Backman. But when Davey said it, my eyes kind of just ‘uh oh, wait a minute now. Let’s play this thing before we start.’

“Usually, you go down to spring training and the manager is just saying that you hope to have a good team and be competitive, but never use the word dominate. Dominate?”

It was an important spring for Wilson after Johnson decided to platoon him and Dykstra in center field — seeing his workload decrease from 154 games in 1984 to just 93 in 1985.

Then disaster nearly struck.

Wilson was hit in the eye by a ball during a run-down drill, sending pieces of glass into it. Surgery was required and he missed the first 23 games of the season. But it could have been much worse.

“To be honest with you, when I got hit in the eye, playing baseball was the least of my worries,” he admitted. “I didn’t want to lose my eye. I didn’t know how bad it was until after the surgery. The doctors kind of informed me what they had done. I guess they didn’t want to offend me at that point because I didn’t need any more stress at that point.

“I was becoming a part-time player and that was an opportunity for me to lose more time, which was a secondary concern I had. Once I was starting to move and get around and do some normal activities, playing time I thought ‘hey, I’m already demoted to a part-time player. I’m just going to lose more time now.'”

Wilson still managed to appear in 123 games with a majority of them coming them coming in left field after the struggles and subsequent release of George Foster for the dominating Mets, who won the NL East by 21.5 games on their way to a 108-win season. He slashed .289/.345/.430 with nine home runs, 45 RBI, and 25 stolen bases.

‘The Best At-Bat Of My Life’

Wilson had struggled through the first nine appearances of his postseason career as the Mets squeaked past the Houston Astros in dramatic fashion, only to fall in an early hole to the Red Sox in the World Series. He went 4-for-his-first-36 with 11 strikeouts.

Johnson kept going back to Wilson, who rewarded him for his confidence by going 4-for-8 with two runs scored in Games 4 and 5, but the Mets were headed back to Shea Stadium facing elimination in a 3-games-to-2 deficit.

After a Carter sacrifice fly in the eighth tied the game at three to force extra innings, the Red Sox scored two in the 10th to take a 5-3 lead.

Wally Backman and Keith Hernandez made two quick outs and the dream of a second-ever championship looked lost for the Mets, as made clear by the now-famous footage of Johnson who got up from his seat in the dugout, paced for a moment, and dropped back down to the bench while the back of his head hit the wall.

“There’s [pitching coach Mel] Stottlemyer and Davey Johnson in the dugout and I’m sitting right to the right of Stottlemeyer. I sat right to the right of those two and there was no hope in their faces. None,” Wilson said. “I don’t care what anyone says, they can deny it all they want, there was no hope. I was saying to myself ‘we have blown this.’ We did. We blew it.

“And then things started happening: Two strikes, base hit. Two strikes, base hit. Two strikes, base hit.”

That wasn’t necessarily the case, but Carter lined a one-strike single to left, Kevin Mitchell lined a one-strike single to center, and Ray Knight looped a two-strike single over second base to score Carter, move Mitchell to third, and get the Mets to within a run.

Up stepped Wilson, who was facing a 2-2 count from Stanley after just four pitches.

Pitch 5: Fouled off. Pitch 6: Fouled off.

“I just did not want to strike out,” Wilson said. “I’m not going to say that I went up there and had it all covered because I didn’t. It was all good. It’s not that I was afraid, I just wasn’t all that confident that I would get a base hit.”

Then the insurmountable pressure was ripped from Wilson’s shoulders as Stanley’s seventh pitch came hurdling toward his legs. Yet, somehow, Wilson managed to evade the pitch and it rolled to the backstop, scoring Mitchell to tie the game at five apiece and moving Knight to second.

“That wild pitch really helped me out,” he admitted. “It was like ‘Thank you, Jesus.'”

Wilson went back to work in the box, fouling off two more pitches from Stanley until that magical 10th pitch resulted in that infamous ground ball that sent Queens into bedlam and the Mets to Game 7 with new life.

“I’ve talked about this game so many times and I’ll be honest with you, I never get tired talking about it,” Wilson said. “Look, I played 12 years and nothing I’ve ever done has come close to what happened in 86. Yes, it wasn’t a line drive, but that was the best at-bat of my life.”

Ask Wilson, and he’ll tell you that Game 7 was just a formality, even if it needed another come-from-behind effort to win it all. But it was just the cherry on a few months in Flushing that simply defied logic.

“Things happened that really don’t happen in your lifetime,” he said. “That whole atmosphere will ever be repeated no matter what another team does. That can’t be duplicated. They can talk about it, but if you weren’t there, you wouldn’t understand.”