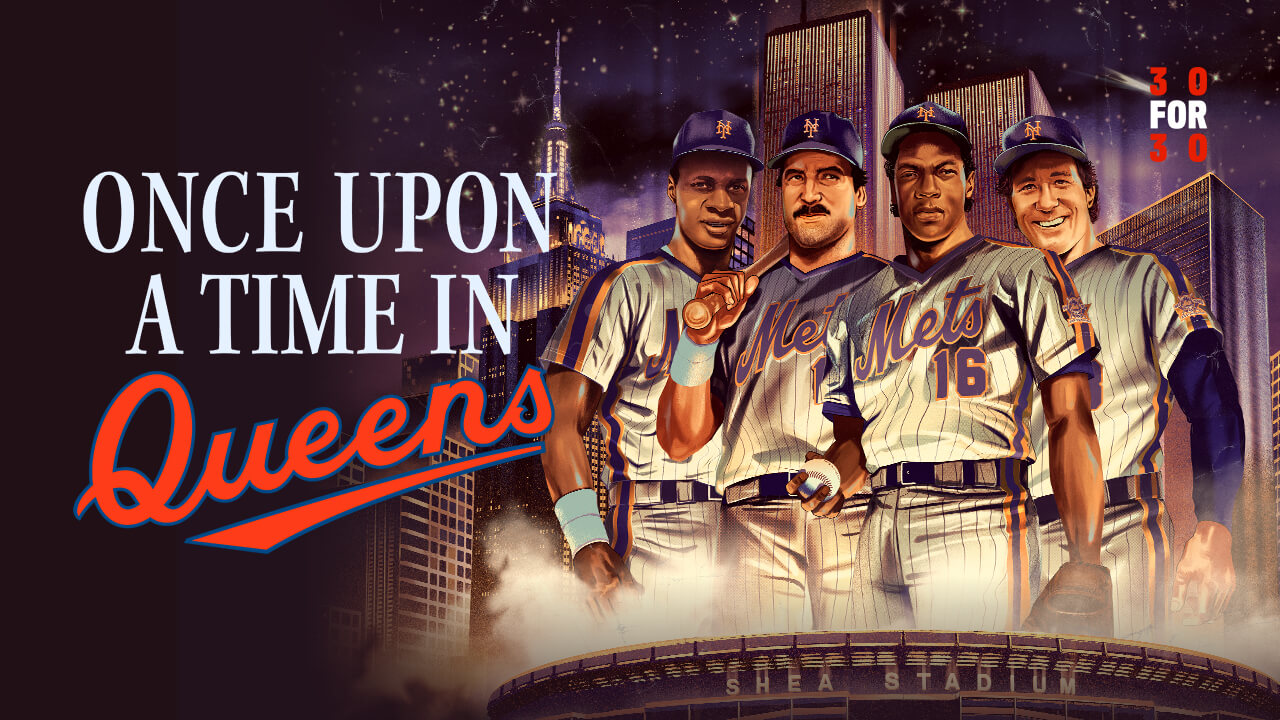

For those paying attention to the build-up of the newest documentary from ESPN’s 30 for 30 chronicling the 1986 New York Mets’ run to a second-ever World Series title, Once Upon A Time In Queens, premiering Tuesday night, did you notice the players and personalities they’ve pushed to the front?

The most familiar and star-studded faces, who obviously deserve to be there — ranging from Keith Hernandez to Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, and Gary Carter. All key cogs to the Mets machine that won 108 games before taking one of the most dramatic Fall Classics ever.

Then there’s Bobby Ojeda: A starting pitcher who you’ll see plenty throughout the documentary, but won’t be the first name, or two, or three mentioned by fans when chronicling the 1986 Mets. Yet he played as big a role as any in an infamous run to a championship.

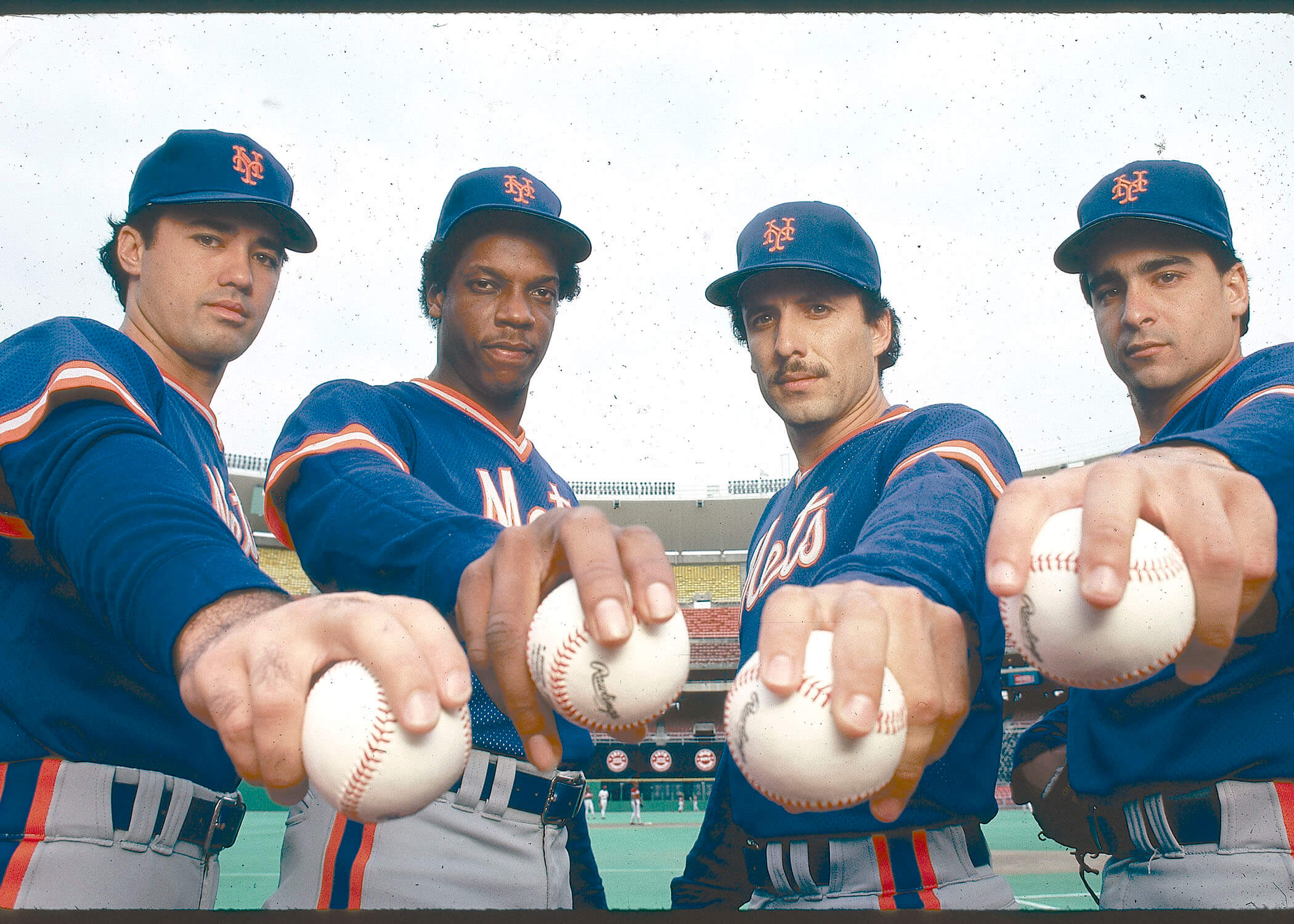

The lefty led a loaded 1986 pitching staff boasting Gooden, Ron Darling, Rick Aguilera, and Sid Fernandez with 18 wins, a 2.57 ERA, and a 1.090 WHIP to go with 148 strikeouts in a career-high 217.1 innings of work.

He was just as valuable in the postseason, going 2-0 with a 2.33 ERA over four games which also included toeing the rubber to start two of the most important games in Mets franchise history — Game 6 of the NLCS against the Houston Astros and Game 6 of the World Series against the Boston Red Sox.

The very same Red Sox who wrote him off just a year prior.

Escaping Boston

A Los Angeles native, Ojeda was signed by the Red Sox as an amateur free agent in 1978 before making his MLB debut with the club in 1980.

His numbers were pedestrian — 44-39 with a 4.21 ERA over five seasons for an organization in the throes of unrest. An upheaval in ownership between the Yawkey Family, Haywood Sullivan, and Buddy LeRoux resulted in toxicity that trickled its way down to the rest of the organization.

“I didn’t care for them at all. I thought they were terrible,” Ojeda told amNewYork Metro. “They didn’t treat people right, myself included.”

John McNamara — the man who led the Red Sox to the American League pennant a year later — was hired in 1985 after stints leading the Oakland Athletics, San Diego Padres, Cincinnati Reds, and most recently before that year, the California Angels.

Ojeda had come in contact with McNamara before, but the new Red Sox manager’s demeanor and apparent forgetfulness all but sealed Ojeda’s desire in wanting out of Boston.

“I had shut McNamara out twice [in 1984],” Ojeda said. “So he comes up to me and says ‘oh, I saw you pitch in the early 80s, you throw the ball okay.’ I walk out of there and say ‘I’m done here, I want out of here.'”

“I can’t believe this ignorant manager could say that after I just showed him up a few months earlier.”

Things got even worse when McNamara moved Ojeda from the starting rotation to the bullpen.

“I knew my time was up but then I got bounced out of the rotation and he wanted to make me a closer, that was never going to work,” he said. “I didn’t have that closer mentality.”

He got his wish in November of 1985 as he was traded to the Mets in a package deal that included Chris Bayer, Tom McCarthy, and John Mitchell for John Christensen, Wes Gardner, La Schelle Tarver, and — a name all Mets fans now know — Calvin Schiraldi.

Making It With The Mets

As documented in Once Upon A Time In Flushing, 1986 was the expected crescendo of a rebuilding effort that saw the Mets emerge from the doldrums of the mid-1970s and early 1980s. They won 90 games in 1984 and 98 in 1985 under manager Davey Johnson — both playoff-less seasons — while Strawberry and Gooden were promoted to the big leagues and Hernandez and Carter were acquired via trades.

Ojeda was looked upon as a more reliable fifth piece of a rotational puzzle that had been sorely missed a year before.

“I came over there and didn’t know the first thing about the 86 Mets. I know they were poised to do well,” Ojeda said. “The entire team was better than the Red Sox. When you’re on a better team, your numbers get better just by showing up.”

And that’s exactly what happened as Ojeda put together the best season of his career while being immersed in a rambunctious culture that featured plenty of fisticuffs — both on and off the field.

The Mets got in four on-field fights that season, and Ojeda himself was arrested in July of 1986 after getting into a fight at a Houston bar with Darling, Aguilera, and infielder Tim Teufel.

A softened league will likely never see a team play with that much aggression and tenacity, but it was an indelible trademark of a team hungry to shed its standing as the No. 2 team in New York and the proverbial punching bag of MLB — a reputation that the franchise still struggles to shed to this day.

“I will tell you something about the importance of camaraderie: When we fought as 86 Mets, it was like, even if you’re wrong, you’re right,” Ojeda said. “We’ll sort that out later, you’re my buddy, you’re my teammate. I don’t care if you tripped an old lady, it must have been her fault, she ran into you. That was that mentality.”

Quite the change of pace from the culture that he was used to in Boston.

“We got into a fight when I was with Boston against the Toronto Blue Jays. One of my teammates, Bruce Kison… he drilled one of their players purposely,” Ojeda remembered. “Benches clear, but one of our players, Jim Rice, goes into their dugout, sits down, and puts his arm around the guy that we just hit because he wasn’t a very good guy. That is the type of atmosphere that was in Boston. It was always about ‘I’ and ‘me’ and ‘I’ and ‘me’.

“With the Mets, we’re like, it’s all of us against everybody else… I loved it.”

So was the foundation of a team that still holds the franchise record with 108 wins, took the NL East by 21.5 games, and streaked into the postseason as heavy World Series favorites.

‘The Right Guy At The Right Time’

Ojeda has had a bad arm since he was 12 years old, often packing it in ice like his father’s idol, Sandy Koufax, did while cementing his place as one of the greatest pitchers of all time in the 1960s with the Dodgers.

Under the career-high workload of 1986 is when Ojeda did further damage to his arm. But with the Mets in the playoffs and Ojeda making his first — and only — foray into October baseball, there was no way he was missing it.

“I signed for $500 and I was not supposed to make it,” Ojeda said. “Now, I’m showing up on the biggest stage, New York, which I loved, and the biggest games of my life, and I wasn’t going to miss it no matter what. So I was taking all kinds of pills, needles.

“I did everything I could and I said if I failed, it’s not because I quit. It’s not because I was a little hurt. I had surgery shortly after [that season] but that was OK. I was willing to throw my crown away to not miss the ’86 playoffs and World Series.”

Ojeda hurled a complete game to beat the legendary Nolan Ryan and the Astros in Game 2 of the NLCS at the Astrodome and was called on to start a Game 6 that was viewed as a must-win despite the Mets holding a 3-2 series advantage with the untouchable Houston ace, Mike Scott, looming for Game 7.

But Ojeda’s arm was acting up, prompting the team’s training staff to give him a shot just before game time to get him loose.

Initially, it looked like it didn’t work as he was slapped for three runs in the first inning to put the Mets in an early hole. But he rebounded, going four more shutout innings while allowing just a single hit.

“I shut them down and Davey [Johnson] stayed with me because Davey knew how much I wanted to be on that field,” Ojeda said. “He stayed with me and I didn’t choke. I hung in there and I was so fortunate to get that game.”

He exited after the fifth inning and was forced to watch for 11 more as the Mets came out on top, 7-6, in 16 wild innings to clinch a ticket to the World Series for the first time since 1973.

Yet that somehow wasn’t the most anxious moments of watching his team after a start in that postseason because 10 days later — after winning Game 3 of the World Series — Ojeda took the mound for Game 6 of the Fall Classic against McNamara and his former Red Sox trying to stave off elimination with Boston one win away from a first title since 1918.

He went six strong innings, allowing two runs on eight hits with three strikeouts, exiting a game that was tied at two.

“I was just the right guy at the right time for not only the team because it worked out we won it, but for myself, because it proved to me I could win the big games,” Ojeda said. “When the money was on the line — and I gambled when I was a kid because we were poor — when our back was against the wall, it really mattered to me to come up big in the big games.

“Not on a rainy Tuesday when we’re 14 games up and I throw a good game. No, but when our backs are against the wall. When we lose and we’re in big, big trouble, I thrived on that.”

You know the rest of that story: Extra innings, the Red Sox pull ahead by two in the 10th inning, the Mets put together a furious two-out rally to tie it before a Mookie Wilson roller etched its place in baseball history.

But where was Ojeda?

“I was in the clubhouse,” Ojeda said. “I went up inside and took off my uniform and put on a towel because I was done. I was watching on the TV. It looked very bleak. Then all of a sudden, a hit. And all of a sudden it started looking a little interesting. So I went down the tunnel, and there’s no shots of me, but I was poking my head out of the tunnel in the dugout to watch what happened.

“I was there, I saw it with my own eyes. I couldn’t run out there because I was in a towel but it was amazing.

“I don’t really share that story because we had enough guys who love to talk about themselves and the narcissistic people who say ‘Oh, I was doing this,’ and I’m like, ‘dude, I started that game.’ I was in a towel, naked, and it was amazing.”

He was fully clothed and able to celebrate with his teammates a night later when the Mets came back again to win Game 7 and a championship that still is the most recent in franchise history.

“We were slightly overrated. I say that because we never won another World Series,” Ojeda admitted. “The wheels fell off — the egos, the narcissism, the mentality blew us apart. But that one magical year with that crazy team and the chaos — it came together in incredible fashion.

“And the phrase ‘It’s never over until it’s over’ should have never been spoken until we did what we did.”